[ad_1]

By Helen Yaffe *

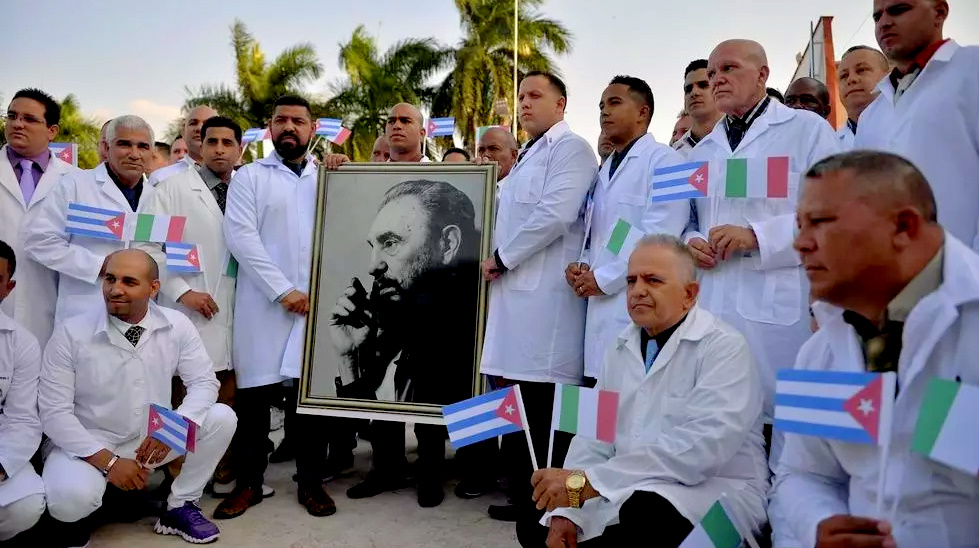

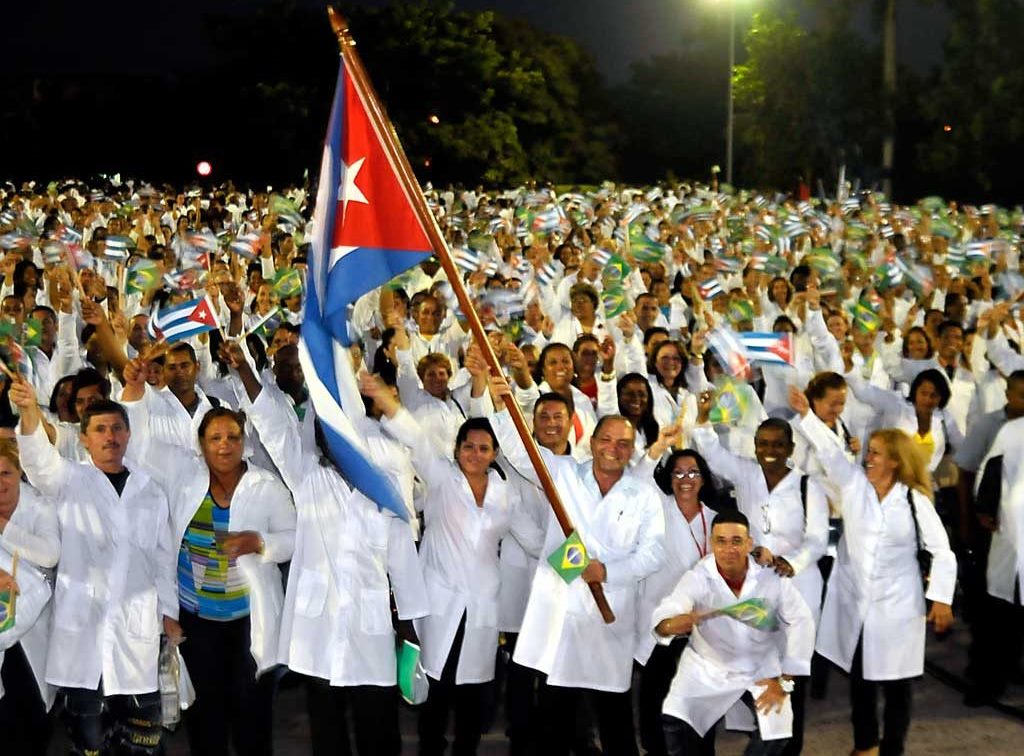

By March 21, Cuba had sent health professionals to 37 countries to collaborate in the fight against the pandemic. Italy received 53 Cuban doctors who had previously worked in West Africa during the deadly Ebola outbreak of 2014. Cuba also took a step over the gap in mid-March, when a cruise ship with more than 600 passengers, mostly British and with a A handful of Covid-19 cases drifted for a week after the United States and neighboring countries denied them permission to dock. Cuba let them in, treated the sick and assisted in their transfer to the flights home. Thus, Cuba is taking a leadership role in the fight against this global pandemic. How can a small Caribbean island, underdeveloped by centuries of colonialism and imperialism, and subject to punitive and extraterritorial sanctions by the United States for 60 years, have so much to offer the world?

In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, capitalist governments have adopted emergency powers, introduced as a “last resort” in societies where neoliberalism has taken deep economic and ideological roots. For decades we have been told that only the free market guarantees efficiency. Now, this global health crisis calls into question such a conception. The Cuban contribution demonstrates that a socialist state can achieve efficient results, measured by social need, not by private benefit.

After the Cuban Revolution of 1959, the revolutionary government developed a free and universal health system, which achieved more doctors per person than any other country in the world. This has been facilitated by free and universal access to education at all levels. The benefits are globally distributed; Some 400,000 Cuban medical professionals have worked abroad in six decades, mainly in poor countries, providing free medical care at home.

Cuba is recognized worldwide both for its infectious disease controls and for disaster risk reduction, generally in response to natural and climate-related disasters. These experiences are being used to combat Covid-19. The Cuban health system seeks prevention over cure, with a network of family doctors who are responsible for community health and who live among their patients. To combat the outbreak, health care personnel perform door-to-door health checks, tests, follow-up contacts, quarantine, and establish a registry of those with underlying health conditions that may need additional care. This is accompanied by public education campaigns and daily updates through a new covid-19-InfoCu application on Infomed, the country’s public health Internet platform. As of March 22, Cuba had 35 confirmed cases of Covid-19, one death, and nearly 1,000 patients under hospital observation, about a third of them foreigners and more than 30,000 people under surveillance at home. On March 23, Cuba closed its borders to all non-resident foreigners in order to control the outbreak, a difficult decision given the importance of tourism revenue for the state.

Interferons as a model for Cuban biotechnology

The work of Cuban medical scientists with interferons in the early 1980s catalyzed the distinctive and early development of their biotech industry. As a result of Fidel Castro’s vision and with the collaboration of medical scientists from the United States and Europe, Cuba made and used interferons for the first time to stop a deadly dengue virus outbreak in 1981. ‘We have taken interferon as a model for the development of biotechnology in our country ‘, announced Doctor Luis Herrera in 1986. Interferon Alfa 2b was developed by the capitalist pharmaceutical industry, however, while its products shared a common active ingredient, the Cuban formulation (components) is different and In this sense, Cuban interferon Alfa 2b is a unique product. Cubans were also the first to use the drug as part of a massive antiviral public health campaign.

Capitalist biotechnology: profits through speculation

The biotech sector was created in the United States with venture capital. The world’s first biotech company, Genetech, was founded in San Francisco in 1976, followed by AMG in Los Angeles in 1980. Internationally, the biotech sector did not make a profit from product sales until 2009. However, thousands of millions of dollars entered the industry. Why is the money from venture capital and the big pharmaceutical industry flowing into an industry where profits are so hard to come by? The answer lies in the role of financial mechanisms, such as Initial Public Offerings (IPOs), Special Purpose Entities (SPEs), Special Purpose Corporations (SPCs) and patent licenses, which enable profits to be made in a high-tech sector with low productivity. Newly created companies generally rely on venture capital investment to finance their initial costs. Once some promising products are developed, venture capitalists and other early-stage investors seek to recoup their investment by having the company issue shares to the public in an IPO.

Biotech companies will only conduct research on products for which a profitable market is deemed to exist, and their development and use are abandoned if that profit does not materialize, if they lose investor support, or if stock prices fall . Biotech products can take up to 20 years to market, and many will never get to that point. In 2002, only about 100 biotech-related drugs hit the market, with the top 10 accounting for almost all sales. Virtually all biopharmaceutical companies that perform IPOs have no products. However, financial speculation allows stock market investors to reap huge profits by trading biopharmaceutical stocks even in the absence of a commercial product.

Furthermore, public investment supports this private gain. The United States Government provides strong financial, legislative and regulatory support to the sector. Two researchers on the subject conclude: “The biopharmaceutical industry has become big business due to big government [y] it remains highly dependent on big government to maintain its commercial success. ” Between 1978 and 2004, the United States Government’s National Institutes of Health (NIH) spent $ 365 billion on life sciences. The commercialization of publicly funded medical research has been legalized. Regulatory assistance is channeled through US patent policy, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval process, and decisions about which drugs or therapies to include in national health care programs.

Therefore, the Cuban biotech industry is not exceptional just because it receives support from the government and public funds. It is exceptional due to the political economy of Cuba; its centrally planned and state-controlled economy, and a development strategy that has prioritized health care, education, and science and technology research since the early 1960s.

Biotechnology with Cuban characteristics

In 1981, the Biological Front, a professional interdisciplinary forum, was created to develop the biotech industry in Cuba, just five years after Genentech in the United States. Although most developing countries had little access to new technologies (recombinant DNA, human gene therapy, biosecurity), Cuban biotechnology expanded and assumed an increasingly strategic role both in the public health sector and in the national economic development plan. It did so despite the blockade of the United States that hinders access to technologies, equipment, materials, financing, and even the exchange of knowledge.

Founded solely through state investment, with financing guaranteed through the state budget, the Cuban biopharmaceutical sector is state-owned, with no private interests or speculative investments. “Our shareholders are 11 million Cubans!” Agustín Lage Dávila, Director of the Center for Molecular Immunology, responded to the head of a multinational pharmaceutical company who asked how many investors they had. The Cuban biopharma is driven by the requirements of public health, and profits are not sought at the national level because the sector is fully integrated with the state health system. The sector has been characterized by a fast track from research and innovation to testing and application. Medicines that Cuba cannot provide or cannot access due to the blockade of the United States must be produced in the country. Today, almost 70% of the drugs used in Cuba are produced internally.

Cooperation prevails over competition, since research and innovations are shared between different institutions. Teams of scientists are established to develop a project from basic science, to product-oriented research, to manufacturing and marketing; activities carried out by different companies in most countries. Dr. Kelvin Lee, Director of Immunology at the Roswell’s Park Cancer Institute in New York, highlights these “surprising” and “unique” characteristics of the Cuban biotechnology sector: “They begin by identifying a need, then discover the science to develop it in the laboratory, manufacture your agent, test it in the Cuban medical system, and then market and sell it abroad. ” Under a license issued by former United States President Barack Obama, Roswell Park is conducting clinical trials with CIMAVax-EGF, Cuba’s innovative lung cancer vaccine. By contrast, in capitalist countries, Dr. Lee explains, a small startup is generally established to research the science behind a “big idea.” It is subsequently bought by a larger company, sometimes twice, who might decide ‘well, you developed this drug for a really rare disease, but we’re going to use it to treat lung cancer,’ and consequently ‘really bombard it. and a great idea disappears «. The disadvantage Cubans face, he adds, is that they cannot chase thousands of good ideas and discard those that don’t work as sunk costs. “They don’t have the resources to do that.” Their access to capital is extremely limited. To make up for that, he says, “They are very thoughtful and careful planners.”

The Cuban cure What have been the fruits of this distinctive Cuban system?

Cuban professionals have received ten gold medals from the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) for 26 years. The first was in 1989 for the world’s first meningitis B vaccine; another was for the Haemophilus type b (Hib) influenza vaccine, another for Heberprot-P for diabetic foot ulcers that affect some 422 million people worldwide. The treatment reduces the need for amputations by 71% and in ten years 71,000 Cubans and 130,000 people in 26 other countries received the treatment. Another WIPO award went to Itolizumab, for treating psoriasis, which also benefited more than 100,000 people worldwide.

In 2015, the World Health Organization announced that Cuba was the first country in the world to eliminate mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Cuba has avoided an AIDS epidemic with antiretroviral drugs produced in the country that stop the transmission of the patient. Cuba’s AIDS mortality curve continues to decline. The universal use of the CIGBs hepatitis B vaccine in newborns means that Cuba should be among the first countries free of hepatitis B. This is one of eight vaccines (of 11 vaccines for 13 diseases) administered to Cuban children. that occur in the Science City of Havana. In ten years, 100 million doses of Cuba’s hepatitis B vaccine were used worldwide.

Cuba achieved a complete program of detection of congenital hypothyroidism before the United States. The Cuban Immunoassay Center developed its own Ultramicroanalytical System (SUMA) team for the prenatal diagnosis of congenital anomalies. In 2017, the Immunoassay Center produced 57 million tests per year for 19 different conditions. The Cuban Neuroscience Center is developing cognitive and biomarker tests for the early detection of Alzheimer’s disease.

The Cuban biotechnology sector has nearly 200 inventions and products marketed in 49 countries, with the capacity for large-scale production of Cuban and generic drugs to export at low cost to developing countries, and associations in nine countries in the global south. . The global pandemic has revealed the difference between Cuba’s state-owned and public health-oriented biotech industry and the speculative search for profit by capitalist companies. Cuba offers a lesson for all of us.

To see the story of how the development of interferons catalyzed the Cuban biotech industry in Cuba, see Chapter 5 “The curious case of the Cuban biotech revolution” in “We are Cuba! How a revolutionary people have survived in a post-Soviet world ”, Yale University Press, 2020. For a shorter version, see here.

Originally posted on Fight Racism! Fight imperialism! No. 275, March / April 2020.

* Professor of Economic and Social History at the University of Glasgow, specializing in Cuban and Latin American development. His new book «We Are Cuba! how a revolutionary people survived in a post-Soviet world »Yale University Press just published it. She is also the author of “Che Guevara: The Economics of Revolution” and co-author with Gavin Brown of “Youth Activism and Solidarity: the Non-Stop Picket Against Apartheid”.

Front Magazine

Cuba and the coronavirus: how Cuban biotechnology came to combat Covid-19 – By Helen Yaffe

The Covid-19 emerged in the Chinese city of Wuhan in late December 2019, and by January 2020 it had already hit Hubei province like a tidal wave, spreading rapidly over China and the rest of the world.

The Chinese state took action to combat the spread and care for the infected. Among the thirty medicines that the Chinese National Health Commission selected to combat the virus was Interferon Alpha 2B, a Cuban antiviral produced in China since 2003 by the Chinese-Cuban joint venture ChangHeber.

Interferon Alfa-2B and Cuban biotechnology

Cuban Interferon Alfa-2B has been shown to be effective in treating viruses with characteristics similar to those of Covid-19. Dr Luis Herrera Martínez, a Cuban specialist in biotechnology, explained that “its use prevents patients with the possibility of aggravating and complicating themselves from reaching that stage and ultimately resulting in death.”

Cuba first developed and used interferons to stop a deadly dengue virus outbreak in 1981, an experience that catalyzed the development of the island’s biotech industry. Today, Cuba is recognized as a world power in this sector.

The first biotechnology company in the world, Genetech, was founded in San Francisco in 1976, followed by AMGen in Los Angeles in 1980. A year later, the Biological Front was created, an interdisciplinary professional forum to develop the industry in Cuba.

While most developing countries had little access to new technologies (recombinant DNA, human gene therapy, biosecurity), Cuban biotechnology expanded and assumed an increasingly strategic role in both public health and the national plan for economic development. This despite the blockade of the United States that hindered access to technologies, equipment, materials, finances and even the exchange of knowledge. Driven by public health demand, the biotech industry has been characterized by the rapidity of its progress from research and innovation to clinical trials and application, as the history of Cuban interferon shows.

The international history of Cuban interferons

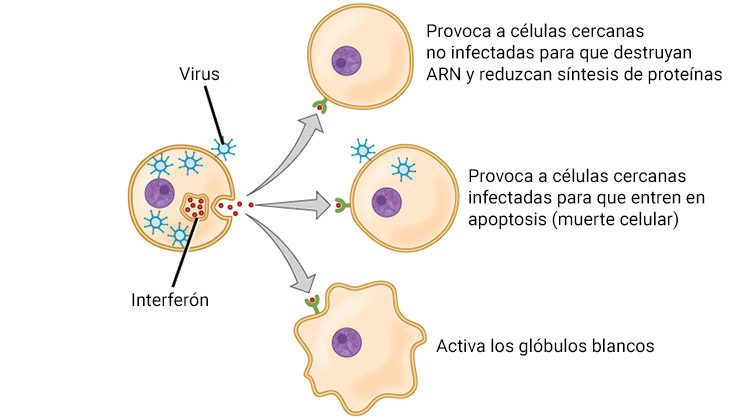

Interferons are signaling proteins produced and released by cells in response to infections that alert nearby cells to increase their antiviral defenses. They were first identified in 1957 by Jean Lindenmann and Aleck Isaacs in London. In the 1960s, Ion Gresser, an American researcher in Paris, demonstrated that interferons stimulate lymphocytes that attack tumors in mice. In the 1970s, American oncologist Randolph Clark Lee undertook this research.

Interferons released by an infected cell cause a defensive reaction in nearby cells (CNX OpenStax, CC BY 4.0, translated into Spanish)

Taking advantage of the improved relations between the US and Cuba during Jimmy Carter’s presidency, Dr. Clark Lee visited Cuba. On this visit, he met with Fidel Castro and convinced him that interferon would be a “miracle” medicine. Shortly after, a Cuban doctor and a hematologist spent a season in Dr Clark Lee’s laboratory, then returned to Cuba with more contacts and with the latest research on interferons.

In March 1981, six Cubans spent twelve days in Finland with Finnish doctor Kari Cantell, who in the 1970s had isolated interferon from human cells and shared the scientific advance by refusing to patent the procedure. Cubans learned to produce large amounts of interferon. Within 45 days of returning to the island, they had produced their first batch of Cuban interferon, the quality of which was confirmed by Cantell’s laboratory in Finland. It arrived just in time.

The 1981 Dengue Epidemic

Weeks later, Cuba suffered an epidemic of dengue, a disease transmitted by mosquitoes. It was the first time that this virulent strain, which can trigger a life-threatening hemorrhagic fever, appeared in the Americas.

The epidemic affected 340,000 Cubans, with 11,000 new cases diagnosed every day at the height of the crisis. 180 people died, including 101 children. Cubans suspected that the CIA had introduced the virus. The US State Department denied it, although a recent Cuban investigation claims to have evidence that the epidemic was introduced from the United States.

The Cuban Ministry of Public Health authorized the use of Cuban interferon to stop the dengue outbreak. It was done in a hurry and mortality decreased. In their historical account, Cuban medical scientists Caballero Torres and López Matilla wrote:

It was the largest interferon prevention and therapy event held in the world. Cuba began holding regular symposia, which quickly attracted international attention.

The first international event in 1983 was prestigious; Cantell gave the opening speech, and Clark assisted with Albert Bruce Sabin, the Polish-American scientist who developed the oral polio vaccine.

Convinced of the contribution and strategic importance of innovative medical science, the Cuban government established the Biological Front in 1981 to develop the sector. Cuban scientists went abroad to study, many in western countries. Their research took more innovative avenues as they experimented with cloning interferon.

When Cantell returned to Cuba in 1986, Cubans had developed the recombinant human Interferon Alfa-2B, which has since benefited thousands of Cubans. With a significant state investment, in 1986 the Cuban Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (CIGB) was inaugurated. By then, Cuba was submerged in another health crisis, a severe outbreak of meningitis B, which further stimulated the country’s biotechnology sector.

The miracle of meningitis in Cuba

In 1976, the outbreaks of meningitis B and C hit Cuba. Since 1916, only a few isolated cases had been seen on the island. Internationally, there were vaccines for meningitis types A and C, but not for type B.

Cuban health authorities obtained a vaccine from a French pharmaceutical company to immunize the population against type C meningitis. However, in the following years cases of type B meningitis began to increase. A team of specialists from different medical science centers, led by the biochemistry Concepción Campa, was established to work intensively in the search for a vaccine.

In 1984, meningitis B had become the main health problem in Cuba. But in 1988, after six years of intense work, the Campa team produced the world’s first successful meningitis B vaccine. A member of the Campa team, Dr Gustavo Sierra, recalled their joy:

This was the time when we were able to say it worked, and it worked in the worst conditions, under the pressure of an epidemic and among the most vulnerable people of the age.

During 1989 and 1990 the three million Cubans in the highest risk categories were vaccinated. Subsequently, 250,000 young people were vaccinated with a combined vaccine against meningitis B and C, VA-MENGOC-BC. It registered 95 percent efficacy, reaching 97 percent among high-risk ages (three months to six years). Cuban meningitis B vaccine received the UN Gold Medal for global innovation. This was the “miracle” of Cuban meningitis.

“I tell my colleagues that you can work thirty years, fourteen hours a day just to enjoy that graph for ten minutes,” Agustín Lage, Director of the Center for Molecular Immunology (CIM), told me, referring to an illustration of the increase and sudden drop in cases of meningitis B in Cuba. “Biotechnology started with this. But then the possibilities of developing an export industry were opened, and today Cuban biotechnology exports to fifty countries. “

Since its first application to combat dengue fever, Cuban interferon has demonstrated its efficacy and safety in the therapy of viral diseases such as hepatitis B and C, herpes zoster, HIV-AIDS, and dengue. Because it interferes with viral multiplication within cells, it has also been used in the treatment of different types of carcinomas. Time will tell if Interferon Alpha-2B proves to be a “miracle” drug in the fight against Covid-19.

LSE

RETURN