[ad_1]

SAO PAULO – “No therapy has been shown to be effective so far,” says a recent survey by scientists at the University of Texas looking at more than 100 clinical trials of drugs to combat Covid-19. The work, commissioned by the AMA (American Medical Association), lists many initiatives that have already failed and some that leave scientists still intrigued, without hiding their frustration at the lack of evidence of the drugs used so far.

ALSO READ:How is the search for the vaccine for Covid-19?

Published in JAMA, the academic journal of AMA, the work scanned the published medical literature until March 25, when 350 clinical tests related to the new coronavirus were recorded. Of these, many were not disease-specific, several refer to vaccines (not medications), and some refer to pediatric patients, who were not the focus of the review. 109 stronger initiatives were left to evaluate in the list of researchers, in addition to more than a thousand studies, which also include reports of isolated cases.

In almost four months of epidemic, among the candidate drugs that have already been left behind is, for example, Tamiflu (oseltamivir). Effective against the flu, the drug was inadvertently used in January in patients with Covid-19 who had not been properly diagnosed. In a later evaluation, the doctors already found that it was not working well. The use of corticosteroids to try to prevent the most damaging inflammatory processes of Covid-19 has also failed.

KNOW MORE:What science learned about the coronavirus in three months

In the midst of the uncertainty scenario, one of the drugs that still has some hope is the antiviral remive, originally created to combat Ebola, but not yet approved for marketing in most countries. A test that collected data from 53 patients in the US. The USA, Italy, Japan and Canada saw an improvement in 36 (68%) of them with the drug. However, since the volunteers were not compared with people who received placebo or other treatments, the authors of the work acknowledge that the evidence of the effectiveness of this medication is insufficient, in an article published on Friday (10) in the New England Journal. of Medicine.

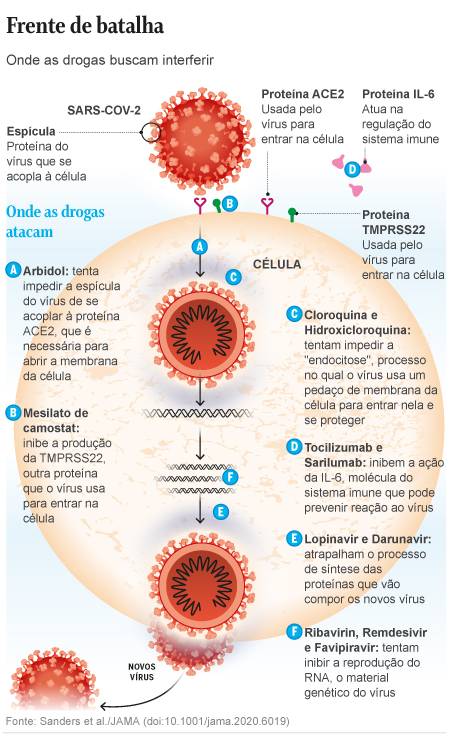

Remdesivir is one of the four treatments chosen for the WHO (World Health Organization) Solidarity program, which articulates a test in larger groups in several countries, which seeks to obtain better evidence of the effectiveness of some medications. The other drugs in the project are Kaletra anti-HIV (a combination of the drugs lopinavir and ritonavir), interferon beta, used for rheumatoid attrition, and the variation of chloroquine / hydroxychloroquine, used against malaria.

However, none of these therapies has obtained results that allow clear conclusions so far.

Hydroxychloroquine, while still attracting the attention of physicians, also did not enthuse the authors of the JAMA review, led by pharmacologist James Sanders. The tests with promising results in France, he says, were conducted in small groups and did not count volunteers excluded from the test due to problems with adaptation to therapy. A similar test in China, also small, but with a more suitable group for comparison, found no visible benefit of chloroquine.

Kaletra, seen as promising at the start of the epidemic, is also in an ambiguous situation. The results of a trial of 199 patients hospitalized for Covod-19 in China, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in March, were unable to see any benefit of the drug. Scientists believe that the effects are perhaps only noticeable to critically ill patients, who will receive the drug in other tests to come.

Hope and side effects.

In the uncertainty scenario, some medicines developed outside the EE axis. USA And Europe still hold a series of hopes.

A drug called Arbidol, approved in Russia and China to treat severe flu, for example, slightly lowered the death rate in a trial of 67 Chinese patients. Camostat mesylate, a Japanese drug approved for pancreatitis, has shown good efficacy in test-tube tests against Covid-19, a degree of evidence that is preliminary, but few of the other drugs currently under evaluation have already done so.

Sanders and his co-authors caution that, despite the rush, maintaining the research safety standard is essential, because it’s not uncommon for a drug used for a new purpose to harm patients rather than help them.

A drug that has been tested against SARS and MERS, a disease caused by other aggressive coronaviruses, ribavirin is now being reconsidered for the pandemic. But the drug already comes from a complicated history of side effects.

“Ribavirin causes severe hematologic toxicity,” the researchers report. “The high doses used in the SARS tests caused hemolytic anemia in more than 60% of patients. In a similar test with MERS, in combination with interferon, 40% of patients ended up needing blood transfusions.”

The concern with toxicity, to a lesser extent, is something that also tests chloroquine and derivatives.

High speed science

Paolo Zanotto, a virologist at USP’s Institute of Biomedical Sciences, read the JAMA article at the request of GLOBO, saying that he considers it “excellent”, but says that the dizzying pace of research production at Covid-19 already makes it Both obsolete. Other drug names with promising potential are emerging in the research community.

– This is an extensive and seminal review, but it doesn’t include more recent studies or drugs like ivermectin, which looks very promising, and the use of heparin, says Zanotto.

The USP researcher, who defends hydroxychloroquine, despite inconclusive evidence, says that more solid results are yet to come.

– We are following a study in which patients had the option of opting for therapy. Most of the hundred who chose to receive concentrated on those who were most at risk due to comorbidities (pre-existing diseases) The group that was treated with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in the outpatient phase had a fifth of the hospitalization rate, it reported.

In the JAMA study, Sanders and its authors recognize the challenge of summarizing the knowledge that has been produced in real time. Brazil is one of the countries that is contributing, albeit modestly, with research protocols.

Fiocruz is testing, for example, the atazanavir / ritonavir combination, and the Sírio Libanês Hospital in São Paulo has patients receiving chloroquine, including some with mild symptoms. A study carried out by Incor (Instituto do Coração), in São Paulo, is using anticoagulant medications for critically ill patients.

“The hectic pace of the medical literature published in Covid-19 means that the recommendations and findings are constantly evolving with new evidence,” Sanders wrote. “What has been published so far is derived exclusively from observational data or small clinical trials, none with more than 250 patients, and this introduces an increased risk of bias or inaccuracy.”