[ad_1]

Image rights

Image rights

Sarita reed

Hajime Yamad arrived in the region with the first wave of Japanese immigrants, in 1929, at the age of 16.

When Brazil decided which side it was on in WWII and broke diplomatic relations with the Axis countries in 1942, a part of the Brazilian population was suddenly persecuted: German, Japanese and Italian immigrants, and their descendants.

In a short time, most of them were locked up in 11 concentration camps throughout the country, whose objective was, among others, to prevent immigrants from acting as infiltrators in their countries of origin.

One of these camps, Tomé-Açu, the only one located in the Amazon region, differed from the others in that it mainly imprisoned Japanese immigrants. There they lived under strict rules, with energy rationing and a curfew, in addition to censorship of correspondence and prohibition of groups.

- ‘Painful and offensive’: the reaction to the wave of people who ‘imitate’ the victims of the Holocaust on TikTok

- Hamburg Angel: the Brazilian who saved Jews from Nazism by granting visas to Brazil and inspires television series

Find out more about this little explored episode of World War II in Brazil.

The creation of the Tomé-Açu field

Until 1942, the Japanese colony that existed on the banks of the Acará River, 200 km from Belém, today the Tomé-Açu municipality, basically lived on the cultivation of vegetables and rice.

The first immigrants arrived in 1929, through the Japanese Plantation Company (Nantaku), which had land in the region. Another important impulse for community consolidation was the founding, in 1935, of the Cooperativa Agrícola de Acará.

However, the development of the community was interrupted with the entry of Brazil into the war.

“Brazil, under great pressure from external relations, carried out actions to contain the ‘enemies of war’, who were foreigners from the Axis: Germans, Italians and Japanese,” explains Priscila Perazzo, professor and researcher at the Municipal University of São Caetano do Sul (USCS) and author of Prisoners of war: the “subjects of the Axis” in the Brazilian concentration camps.

“So the government decides to set up camps where the people of these countries can do internships.”

Surrounded by the Amazon rainforest and accessible only by river, the Japanese community that formed around Nantaku and the Cooperative was an ideal candidate to host one of these fields.

On April 17, 1942, the Japanese lost their property rights through a declaration of confiscation, and the village on the Acará River was isolated. The Tomé-Açu concentration camp is born.

Image rights

Reproduction of the book By land, sky and sea: history

House that was part of the Tomé-Açu concentration camp

A good part of the 49 families that lived in the region, at that time, were peasants and had little knowledge about the confrontations that took place in their homeland. Even so, they were considered “prisoners of war”, a term generally used for military personnel captured in combat, but which, at that time, was also used for civilians.

The figures are inaccurate, but it is estimated that, during its three years of existence in the camp, some 480 families of Japanese, 32 Germans and some Italians ended up there.

Much of it came from the capital Belém, this is the case of the 79-year-old Elson Eguchi family. Her father, Yasuji, went from Japan to Peru, a country with significant Japanese immigration. But it was in Brazil where she settled.

With the war, Yasuji was forcibly displaced from Belém to Tomé-Açu. “My father worked as a cook in Belém. The government took him out and threw him here, in Tomé-Açu, as a concentration camp,” Elson reports.

Image rights

Personal file

Elson Eguchi spent his early childhood in the concentration camp.

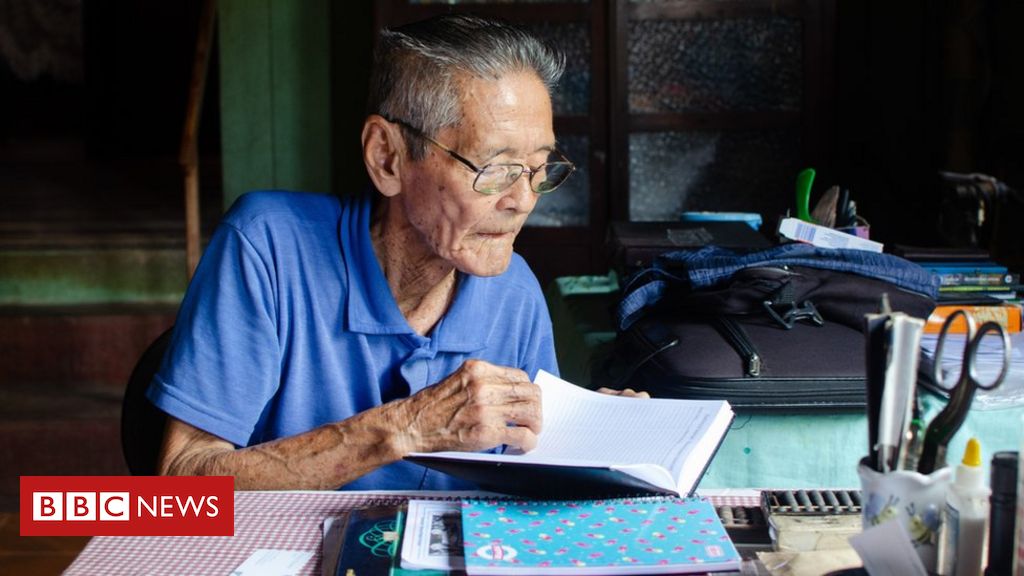

In the capital of Pará, life for the Japanese was not easy either. “In Belém, the Brazilians looted, burned the shops, the houses of the Japanese. Many were left without a place to live,” says Hajime Yamada, 94.

He arrived in the Acará region in 1929, in the first wave of immigrants, when he was 2 years old. Since then, she has lived in Tomé-Açu and has lived through years of hardship.

Many Japanese were also brought from the Amazon, including Manaus, 1,317 km from Tomé-Açu. The leaders of the Companhia Industrial Amazonense were taken to the countryside and the local press began to call them “fifth column”, a term used, in the context of war, to designate spies, saboteurs and traitors in the service of another country.

In 2011, the Legislative Assembly of Amazonas made an official apology to Japanese immigrants for abuses committed during World War II.

As it was or field

Throughout history, concentration camps have taken various forms. In the case of Tomé-Açu, the immigrant colony was isolated within the perimeter of the camp. The houses, the hospital and other community buildings were, overnight, subordinate to the power of the State.

“As it was a village practically lost in the Amazon, whose only access was by boat, at the time when the State controlled the boat, the community ended up isolated,” explains Perazzo.

Many of the immigrants who were forced to move were not forced to stay in cells, but they also had no place to stay or feed. Yamada reports that at least two families remained on his property until the end of the war.

“Here at home were the Takashima and Watabi families. It took a year or so before the war ended. We were able to set up a tent quickly, because they came from Belém without a home, with nothing, just with their clothes on. Everyone gave support.” , informs.

Thus, the countryside was structured like a royal city. Surveillance and security were guaranteed by a military detachment, under the administration of Captain João Evangelista Filho.

Image rights

Museum of the History of Japanese Immigration in Brazil

Municipal warehouse of Tomé-Açu. The only access to the region was by boat.

Routine in the concentration camp

The routine in the Tomé-Açu camp was one of deprivation, although it was not compared to that of the death camps of Nazi Germany.

Starting with the confiscation of immigrant assets. The Brazilian authorities took books, radios, weapons and boats, who sometimes enjoyed these goods for their own benefit.

Cutting off communication between immigrants and the outside world was a priority for the Brazilian government. The correspondence was censored at the post offices in Belém and, “if there was a complaint that someone was listening to the radio in Japan, for example, the police would surely knock on those people’s doors and they would have serious problems,” says Perazzo.

Nor was he allowed to meet the other inhabitants of the camp. “People were monitored daily by local police forces so that they did not communicate with each other. If they were caught with such a practice, they would be penalized,” explains Elton Sousa, professor and researcher at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA) and co-author of the book. and documentary By land, sky and sea: stories and memories of the Second World War in the Amazon.

“If there were three or four Japanese together, talking, the police would take them away, arrest them. They had no freedom,” Yamada says. “They thought we were planning war deals, but there was nothing like that.”

Image rights

Museum of the History of Japanese Immigration in Brazil

The routine in the Tomé-Açu camp was one of deprivation, despite not being comparable to that of the Nazi camps.

In addition to the restrictions on locomotion and communication, the immigrants dedicated themselves to subsistence in the countryside, according to manual labor regulations stipulated by the government, Perazzo explains: “There were those who worked in carpentry, carpentry, agriculture. It varies.”

The field also suffered energy rationing and, at 9 pm, the curfew sounded.

The end of the war

The compound lasted until 1945, when the camps were extinguished after the end of the war was decreed. But the consequences of the period of persecution lasted for decades.

Stigmatized and impoverished, many immigrants struggled to find work or have their own businesses.

“After the war ended, the government released these people as if it had no responsibility to dismantle their lives,” Perazzo explains.

“They did not return to their countries of origin. Either they were immigrants already established in Brazil or people who could not return, so they sought life in a different way.”

Combined with the period of reclusion, the postwar Tomé-Açu offered few prospects for the settlers, which is why many of them left the region. “They went to Belém, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Paraná,” Yamada recalls.

“They all helped with a little money, within their means, to survive.”

A few years later, however, the city took off economically with the boom of black pepper, becoming the world’s largest producer of this product.

Image rights

Museum of the History of Japanese Immigration in Brazil

Harvesting black pepper in Tomé-Açu

The golden age of pepper ended in the late 1960s, when a disease, fusariosis, decimated the plantations, while the value of the spice suffered a sharp drop on the international market.

Today, about 1,000 descendants of Japanese live in Tomé-Açu. “It is a society whose local culture is permeated with traits strongly marked by Japanese culture,” says Sousa.

In recent decades, the city has developed thanks to the adoption of a sustainable agroforestry production system.

Image rights

Vinicius Fontana

‘It is a society whose local culture is permeated with traits strongly marked by Japanese culture’

The buildings of World War II were almost completely destroyed in the region and there are few photographic records of the time.

But the concentration camp remains in the memory of those who lived there and of those who preserve the stories of their ancestors.

- Click to subscribe to the BBC News Brasil YouTube channel

Have you seen our new videos on Youtube? Subscribe to our channel!