[ad_1]

The relationship between idols was marked by exchanges of spikes and declarations of mutual admiration.

Eternalized in shouts of cheers, like the Argentine “Brazil, tell me how you feel” and the Brazilian “A thousand goals, only Pelé”, the rivalry between the two great soccer idols in neighboring countries lasted decades, fueled by the sports press.

Marked by the exchange of quills through the pages of the newspapers, but also by declarations of mutual admiration, the relationship between the two geniuses of the ball came and went.

This Wednesday (11/25), in which Maradona died at age 60, affection prevailed.

“What sad news. I lost a great friend and the world lost a legend,” wrote Pelé, on his social networks. “There is still much to say, but for now, may God give strength to family members. I hope that one day we can play ball together in heaven.”

Origin of the rivalry

Scholars of soccer history disagree on the origin of the rivalry between the players.

“Until 1998, this rivalry did not exist. In the Argentine press, Pelé was indisputably treated as the greatest in history and Maradona as his heir”, says Ronaldo George Helal, sociologist and professor at the UERJ (State University of Rio de Janeiro ). who studied the coverage of the Buenos Aires World Cup press from 1970 to 2006.

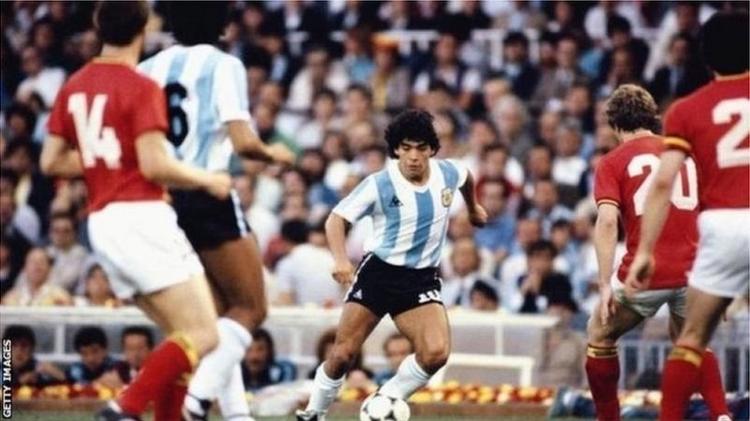

According to the researcher, the rivalry in 1982 – the year the World Cup was held in Spain and Italy won – was between Maradona and Zico.

And even in 1990, when Pelé was a columnist for Clarín during the Cup that year, the Brazilian was presented by the Argentine newspaper as “the one who was the best in the history of football.”

According to Helal, the rivalry between the players grows stronger with the election by FIFA, in December 2000, of the best player of the 20th century. In the dispute, Pelé won among the specialists chosen by the entity. Maradona, on the other hand, was elected by popular vote on the internet.

“Upon receiving his award, Pelé invited his rival to come up on stage, but he left, a rebel,” recalls journalist Alex Sabino, in a report by Folha de S. Paulo.

Waiting for the Messiah

For Celso Unzelte, a journalist for ESPN Brazil and a researcher on soccer history, the rivalry has much more remote origins.

“This rivalry comes from before Maradona was born,” jokes Unzelte. “When a 17-year-old black boy shows up in Brazil, winning the 1958 World Cup, Argentines start to wait for their messiah.”

According to the journalist, since then, every time a skilled player appeared in Argentina, he was automatically compared to Pelé. Say Stefano.

“When Maradona appeared, the Brazilian sports press at the time said: ‘He is painting another that Argentina hopes will be his Pele.’

Similarities and differences

Unzelte recalls that, at the 1978 World Cup, held in Argentina during the military dictatorship, Maradona was 17 years old, the same age as Pelé in 1958. But, at that time, the Argentine idol was not summoned by coach César Luis Menotti.

“And then the comparisons begin, although from a football perspective they were very different,” says Unzelte.

“Maradona was brilliant, but he had practically only his left leg. He didn’t head and didn’t have other abilities like Pelé. Maradona wasn’t exactly a scorer, he was far from a thousand goals.”

At the same time, says the journalist, there were characteristics that united them. “If Pelé helped change the history of Santos, Maradona, after a certain failure in Barcelona, helped change the history of Napoli in Italy.”

The theme of affection

For Helal, the main difference between the Brazilian and the Argentine is in what he calls “the issue of affection.”

“The Brazilian does not admit any comparison of Pelé with anyone. Pelé was the greatest in history and at the time. But here there is not as much affection for Pelé as the Argentines feel for Maradona,” he evaluates.

“In the streets of Buenos Aires you can see Maradona in the kiosks, next to Che Guevara. In the social science bookstores next to Jorge Luis Borges and Julio Cortázar. In the public road of Caminito, there is a statue of Maradona next to Perón and Avoid it ”, he highlights.

For the sociologist, all this indicates that Maradona is in a category of affection in Argentina that Pelé never had in Brazil. “Pelé has always been seen to be very linked to power and he has always been criticized a lot,” he says, citing, for example, the demands that are made of Brazilians for not taking a clear position on racism.

Unzelte agrees with the assessment. “As for idolatry, I think Maradona is closer to Ayrton Senna. Maradona has just entered the altar of the Argentine homeland today, along with Carlos Gardel and Evita Perón. Not here. Unfortunately for Pelé, he considers himself more recognized in abroad than here. In Brazil, it is more controversial. “

The meeting of ‘King with god‘

Both researchers recall an episode that reveals the affection that existed between the two players.

In 2005, Maradona received the Brazilian at the premiere of the program The Night of Ten, one talk show presented by the Argentine idol, announced by Argentine TV at that time as the meeting “of the King with God.” Rei was Pele.

“Then we learned that, in the 1990s, Pelé tried to bring Maradona to Santos. Something went wrong, but Pelé tried,” says Helal. “So I think they had a very complicated relationship at times, but then they cut the edges.”

Unzelte also remembers that, on that occasion, Pelé played a song on guitar that said: “Who am I, Maradona? Who are you? You want to be me and I want to be you.”

“I think the rivalry between them was much less personal, and much more between the two countries,” says the journalist.

At the end of the program, recalls the UERJ professor, the Argentine was asked who was the best: him or Pelé, to which Maradona replied: “My mother thinks it’s me and her mother thinks it’s him.”