[ad_1]

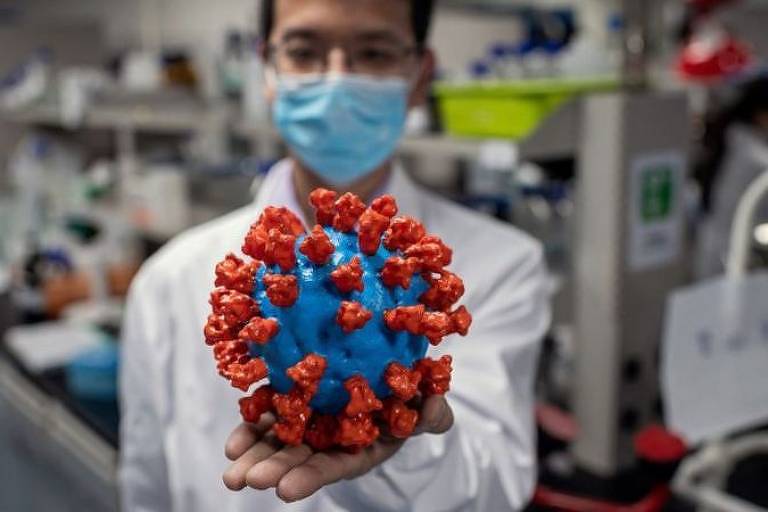

In January 2020, Chinese researchers revealed to the world the first genome of a virus that was beginning to infect humans and until then it was restricted to the Asian country, Sars-CoV-2.

Almost a year later, after sickening more than 78 million people around the world, scientists have already shared millions of genomes of this coronavirus on the collaborative online platform Gisaid. And, as expected, these new genetic “identity papers” show that the coronavirus is not exactly the same as the one that was first introduced in January 2020 – it has mutated, often accidental changes in the genetic material of the virus.

Genomes with similar mutations form “variants”, “strains” or “strains” of the virus, which, despite harboring these internal differences, is still Sars-CoV-2, according to the researchers interviewed by BBC News Brazil.

One of these strains, identified as B.1.1.7, caused 40 countries to close their borders with the UK this week. British researchers and government officials warned that the variant has become prevalent across much of the country, including London, undergoing more than 10 mutations that may have facilitated its transmission. This strain has also been found in Australia, Denmark, Italy, Iceland, and the Netherlands, among others.

In Brazil, a new strain, characterized by up to five mutations, was identified for the first time in samples from the state of Rio de Janeiro and presented by researchers on Tuesday (12/22). According to the team, the strain was derived from another variant circulating in the country, B.1.1.28, originating in Europe.

Both cases raised the alarm that such mutations could give more power to Sars-CoV-2, for example, favoring its transmission capacity or the severity of the infection. However, according to the researchers, there is not enough evidence so far that this worrisome scenario is happening or that new strains jeopardize the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines.

“There is no need to panic. In the midst of a pandemic, with many people and viruses circulating, it is natural for it to mutate. It is trying to escape the host’s immune system, it is normal,” summarizes Ana Tereza Ribeiro de Vasconcelos, ahead of the investigation. with genomes from Rio and coordinator of the Bioinformatics Laboratory of the National Laboratory for Scientific Computing (LNCC).

“What we are doing is genomic surveillance to see how the virus is evolving in Brazil. This is important to monitor whether there will be mutations that may give it some characteristic of greater infectivity, of transmissibility,” says Vasconcelos, adding that in the lineage identified in Rio de Janeiro, there is no evidence that the virus has had this greater danger.

“In England, however, more data is still needed to show that this lineage (B.1.1.7) is more infectious, for example by associating the mutations with information from patients who have become more serious or sick for a longer time.” .

The researcher, a doctor in biological sciences from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), acknowledges, however, that “if the virus becomes more dangerous it will be due to mutations.”

“That is why it is important to monitor them,” says Vasconcelos.

“There are changes in some parts of the genome that nothing happens. But if it happens in a key location that affects the link (of the pathogen) with the immune system, then it is worrying.”

14 mutations in the UK variant

Although institutions such as the World Health Organization (WHO) point out that it is too early to draw conclusions about the variant that gained prominence in the United Kingdom, preliminary studies have pointed to an unusual number of mutations14, some of which possibly affect the disease. gene that encodes the spike protein, a kind of key that the coronavirus uses to access human cells.

However, mutations alone are not enough to indicate a greater threat from the virus, recalls Paola Cristina Resende, a researcher at the Laboratory of Respiratory Viruses and Measles at the Oswaldo Cruz Institute (IOC / Fiocruz).

“Even if the viruses have mutations and / or are from different lineages, this does not mean that they are phenotypically different. That is, it does not mean that they have different characteristics ”, explains the researcher, a doctor in molecular and cellular biology.

“The characterization of the lineage is very refined, it was adopted at the beginning of the pandemic to characterize viruses with certain groups of mutations that are circulating around the world. This is more of an epidemiological characterization, to understand the spread of the virus.”

“Complementary analyzes should accompany genomic analyzes to confirm hypotheses in tests such as: greater viral dispersion; greater severity of the disease; antiviral resistance, among others ”, he adds.

What about vaccines?

If the coronavirus undergoes major changes in the genome, it is possible to imagine that the vaccines currently studied or applied worldwide will not work in these new configurations.

For now, however, the researchers dismiss this alarming scenario because the main vaccines train the immune system to attack different parts of the virus, targeting a larger target than specific parts that may have been mutated.

In addition, recalls Ana Tereza Ribeiro de Vasconcelos, knowledge about other coronaviruses shows that they mutate much less than influenza viruses, for which different vaccine formulas must be made each year, such a change.

However, speaking to BBC News in England, Cambridge University Professor Ravi Gupta expressed concern about the mutations that the coronavirus has already shown, such as in the B.1.1.7 strain.

“If the way to add more mutations is open, it starts to be worrisome,” Gupta said.

“This virus is potentially on a vaccine escape route. It has taken the first steps in that direction.”

How mutations occur

It may not seem like it, but the mutations that can sometimes favor an invading organism don’t happen “on purpose”, but by chance.

Most of the time, errors in the process of copying genetic material cause changes, but to a lesser extent, radiation and chemicals (such as tar in cigarette smoke) can also do so.

As in any evolutionary process, biological advantages are highlighted in the natural selection process and are reproduced. This is what can happen with some beneficial characteristic derived from some mutation.

But these changes do not always have advantages, explains virologist Rômulo Neris.

“When it infects a cell, the virus has to multiply. And to do that, the cell reads the virus genome, which is where the instructions on how to make more viruses are. The mutation occurs the moment the genome is copied.” . , explains the researcher, a doctoral student at UFRJ.

“Most of the time, the mutation just doesn’t do anything, it doesn’t cause significant changes in the virus. In other cases, it can be harmful to the virus; when it does, the mutation is not transmitted, because the virus just proliferates.”

“Ultimately, the mutation particles can acquire some new function or modify some function that already existed. Some of these mutations can, for example, give more affinity of virus elements to cellular proteins, potentially increasing the possibilities Other types of mutations can give the virus the ability to evade the immune response. “

“The accumulation of these mutations can ultimately characterize a new organism, such as the new coronavirus. At some point, another parent virus, which so far appears to be a bat virus, has undergone enough adaptations in the genome to to successfully infect humans. “