In 2017, NASA’s space probe discovered a huge, man-made ‘barrier’ around the Earth.

And tests have confirmed that it is actually affecting the space weather outside our planet’s atmosphere.

This means that not only are we changing the Earth so seriously, scientists are calling for a whole new geographical age to be named after us – our activities are also changing space.

But the good news is that unlike our influence on the planet, the interesting bubble we created in space is actually working in our favor.

Back in 2012, NASA began testing two spacecraft to work together as they flickered through the Earth’s Van Allen belt at a speed of about 3,200 km / h (2,000 miles per hour).

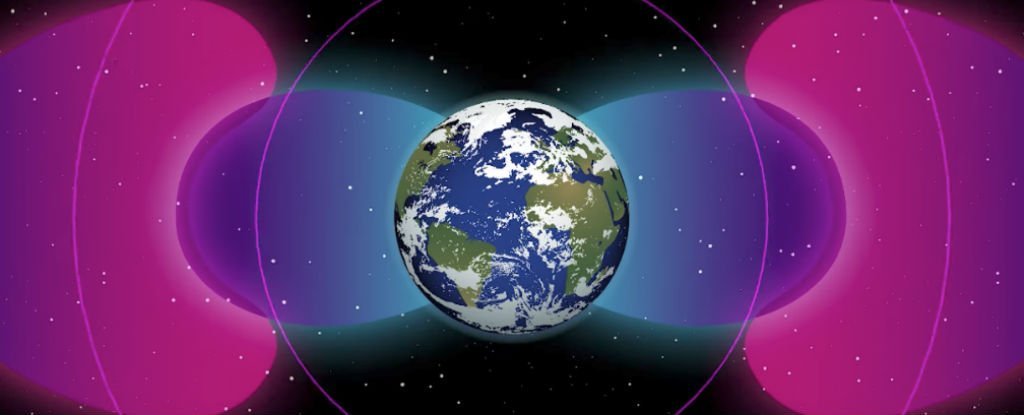

Our planet is surrounded by two such radiation belts (and a temporary third) – the inner belt about 640 to 9,600 km above the Earth’s surface. (400 to 6,000 miles), while the outer belt has an itude of about 13,500 to 58,000 km. (8,400 to 36,000 miles).

In 2017, Van Allen probes discovered something unexpected because they monitor the activity of charged particles caught in the Earth’s magnetic field – this dangerous solar discharge is being exposed by some kind of low frequency barrier.

When researchers investigated, they found that this barrier had been actively pushing the Van Allen belt from Earth for the past few decades, and now the lower limit of radiation streams is actually farther away than ours in the 1960s.

So what has changed?

A certain type of transmission, called very low frequency (VLF) radio communications, has become more common since the 60’s, and the NASA team has confirmed how and where they can influence certain particles moving in space.

In other words, thanks to VLF, we now have anthropogenic (or man-made) space weather.

“Many experiments and observations have found that, under the right conditions, radio communications signals in the VLF frequency range can in fact affect the properties of the high-energy radiation environment around the Earth.” Ericsson from MIT Hastack Observatory in Massachusetts, last 2017.

Most of us don’t have much to do with VLF signals in our daily lives, but it is a major base in many engineering, scientific and military operations.

With a frequency of 3 to 30 kHz, they are too weak to carry audio dio transmission, but they are suitable for transmitting coded messages over long distances or under cold water.

The most common use of VLF signals is to communicate with deep-sea submarines, but because their vast wavelengths extend around large obstacles such as mountain ranges, they are also used to achieve transmission over difficult terrain.

VLF The signals were not intended to go anywhere other than Earth, but it turns out that they are leaking into the space around our planet, and they have been lengthened for a long time to form a huge protective bubble.

When Van Allen Probes compared the location of the VLF bubble to the boundary of the Earth’s radiation belts, he initially felt like an interesting coincidence – “The outer edge of the VLF bubble corresponds exactly to the inner edge of the Van Allen radiation belt.” NASA said.

But once they realized that VLF signals could actually affect the motion of charged particles inside this radiation belt, they realized that our inadvertent man-made barrier was gradually pushing them back.

One of the teams, Dan Baker, from the University of Colorado’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, called this “impenetrable barrier.”

While our defensive VLF bubble is probably the best man-made effect we humans have ever had on the space surrounding our planet, it’s certainly not the only one – we’ve been making our place in space since the 19th century and especially the last 50 years, when nuclear explosions were all the rage.

“These explosions created an artificial radiation belt near the Earth, causing extensive damage to some satellites,” the NASA team explained.

“Other anthropological influences on the atmosphere of space include chemical release experiments, high-frequency wave heat of the ionosphere and the interaction of VLF waves with radiation belts.”

Astronomer Carl Sagan once wanted to find specific signs of life on Earth from space – it turns out, there’s a lie if you know where to look.

The research was published by Science space reviews.

A version of this story was first published in May 2017.

.