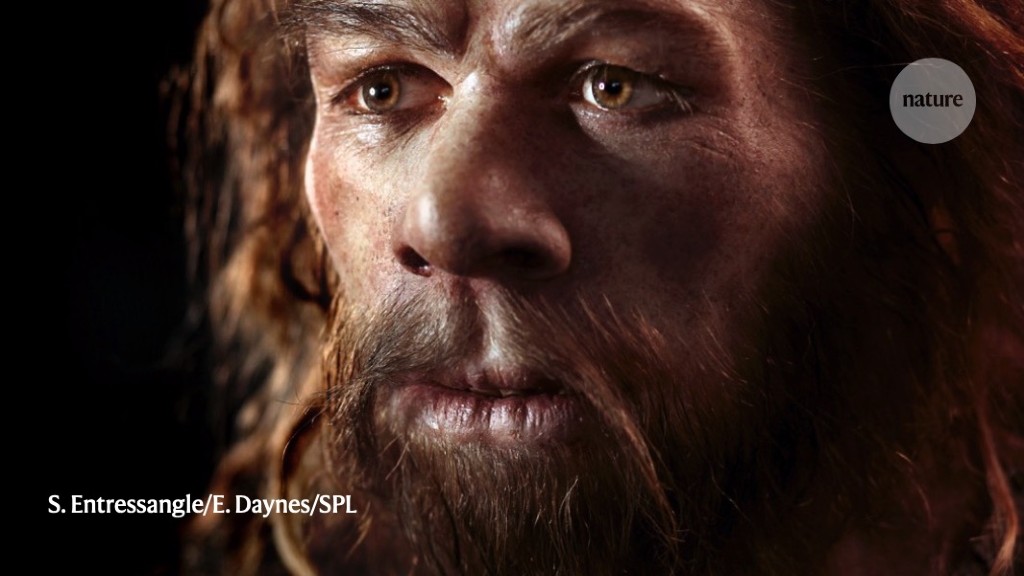

Neanderthals lived difficult lives. Ice age hunter-gatherers made their living in western Eurasia, hunting mammoths, bison, and other dangerous animals.

Despite their rough and fallen existence, Neanderthals had a biological predisposition to increased pain sensation, a first published genomic study finds in its class. Current biology July 23one. Evolutionary geneticists discovered that ancient human relatives carried three mutations in a gene that encodes the Na protein.V1.7, which transmits painful sensations to the spinal cord and brain. They also showed that in a sample of Britons, those who had inherited the Neanderthal version of NaV1.7 tend to experience more pain than others.

“For me, it is a prime example of how we may begin to get an idea about Neanderthal physiology using current people as transgenic models,” says Svante Pääbo at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, who led Work with Hugo Zeberg at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

Pain sensitive protein

The researchers only have access to a few Neanderthal genomes, and most of them have been sequenced at low resolution. This has made it difficult to identify mutations that evolved after their lineage separated from that of humans about 500,000-750,000 years ago. But in recent years, Pääbo and his team have generated three high-quality Neanderthal genomes from DNA found in caves in Croatia and Russia. This allows them to confidently identify mutations that were probably common in Neanderthals, but very rare in humans.

Mutations in a gene called SCN9A – which encodes NaV1.7 protein: It was highlighted because all Neanderthals had three mutations that alter the shape of the protein. The mutated version of the gene was found on both sets of chromosomes in all three Neanderthals, suggesting that it was common in all of their populations.

N / AV1.7 acts on the nerves of the body, where it participates in the control of whether the painful signals and to what extent they are transmitted to the spinal cord and the brain. “People have described it as a volume knob, which establishes pain gain in nerve fibers,” says Zeberg. Some people with extremely rare genetic mutations that turn off the protein do not feel pain.twowhile other changes may predispose people to chronic pain3.

To investigate how mutations might have altered Neanderthal nerves, Zeberg voiced his version of NaV1.7 in frog eggs and human kidney cells: useful model systems to characterize proteins that control neural impulses. The protein was more active in cells with all three mutations than in cells without the changes. In nerve fibers, this would lower the threshold for transmitting a painful signal, Zeberg says.

He and Pääbo searched for humans with the Neanderthal version of NaV1.7. About 0.4% of participants in the UK Biobank, a genome database of half a million Britons, who reported pain symptoms had a copy of the mutated gene. No one had two, like Neanderthals. Participants with the mutated version of the gene were approximately 7% more likely to report pain in their lives than people without it.

Sensitive Neanderthals

“This is beautiful work,” because it shows how aspects of Neanderthal physiology can be reconstructed by studying modern humans, says Cedric Boeckx, a neuroscientist at the Catalan Institute for Research and Advanced Studies in Barcelona, Spain. In a 2019 study, Boeckx flagged three other proteins involved in pain perception that differ between modern humans and Neanderthals.4 4. Such changes may indicate differences in resistance between the two species, he says.

Pääbo and Zeberg caution that their findings do not necessarily mean that Neanderthals would have felt more pain than modern humans. Sensations transmitted by NaV1.7 are processed and modified in the spinal cord and brain, which also contributes to the subjective experience of pain.

Gary Lewin, a neuroscientist at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in Berlin, notes that Neanderthal variants impart only a small effect on the function of NaV1.7 – and much less than other mutations associated with chronic pain. “It is hard to imagine why a Neanderthal would want to be more sensitive to pain,” she adds.

It is not clear if the mutations evolved because they were beneficial. Neanderthal populations were small and lacked genetic diversity, conditions that may help harmful mutations persist. But Pääbo says the change “smells” like a product of natural selection. He plans to sequence the genomes of about 100 Neanderthals, which could help provide answers.

In any case, “pain is somewhat adaptive,” says Zeberg. “It is not specifically wrong to feel pain.”