[ad_1]

In Russia, the number of deaths from coronaviruses exceeded 5,000 this week, and the total number of infections exceeded 424,000. Around 9 thousand are still confirmed in Russia per day. However, quarantine conditions continue to improve in the country, and Putin announced last week that the pandemic peaked in the past, so preparations can be made for a postponed Victory Day parade from May 9 to June 24, a referendum on constitutional amendments on July 1. .

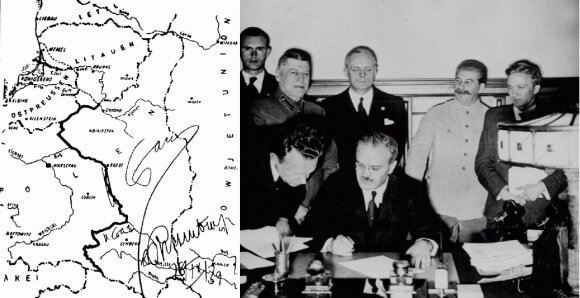

At the same time, this week, Russia has stepped up its aggressive rhetoric against neighboring states. A bill registered in the Russian Duma to revoke the conviction of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in 1989 In the Congress of People’s Deputies.

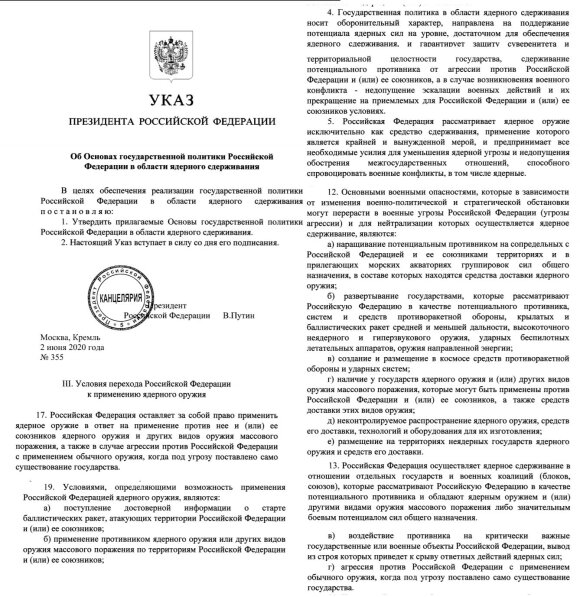

And on Tuesday, Putin signed the order no. 355 “On the framework of state policy in the field of nuclear deterrence”. At first glance, the documents logically establishing the continuation of Russia’s international and security policy are not special and will not have significant consequences. In reality, however, they both provide a legal basis for possible future actions by the Kremlin.

Undo the sentence, so what?

A proposal was made in the Russian Duma to override the 1989 decision of the Soviet Council of People’s Deputies to condemn the signing of the 1939 Soviet-German Non-Aggression Pact.

In 1989, the Congress of the People’s Deputies of the USSR formed a commission in 1939. August 23 to evaluate the non-aggression pact politically and legally, chaired by Aleksandras Jakovlevas, and among the members of the commission were Lithuanian representatives: Vytautas Landsbergis, Justinas Marcinkevičius, Kazimieras Motieka, Zita Šličytė. After a long discussion in a resolution of December 24, the Congress of the People’s Deputies of the USSR declared the secret agreements legally unfounded and invalid from the moment of their signing. This was also pointed out by Putin in his speech in 2007.

In recent years, however, the idea of rehabilitating the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in Russia has been revived, both on individual and state-level initiatives, as the Russian Foreign Ministry is already embroiled in conflict with Poland and the Baltic states on the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Russia has repeatedly hinted that Lithuania should be grateful to the Kremlin for the return of Vilnius and Klaipeda. Now the consequence of such languages is the bill mentioned above.

© Wikimedia Commons

Its author is Alexei Zhuravliov, a parliamentarian famous for his nationalist statements, who brought together a group of dozens of “scientists, officers and public figures” and declared in a joint letter that “this document is not in line with historical justice and was adopted in the face of political instability. ” The bill has already been registered in the Duma.

Lithuania’s Foreign Minister Linas Linkevičius has already called the initiative an attempt to falsify history. And it’s probably not the last. According to L. Linkevičius, it was agreed with colleagues from Latvia, Estonia and Poland to “closely monitor the situation” with respect to attempts to distort historical events.

At first glance, even if this bill were to be adopted, its legal force would be nil and would not pose a direct threat to Lithuania. It is impossible to retroactively validate the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact that have been declared invalid.

Under international law, state recognition cannot be revoked either. After all, it was Lithuania and Russia (true, then the Russian Federal Socialist Republic of Russia) in 1991. The agreement on the framework of cross-border relations signed on July 29, 2006 not only establishes “the inalienable right to independence of the state “, but also emphasizes that both parties mutually recognize each other as” full subjects of international law and sovereign states in accordance with their state state enshrined in basic acts. ” Such is the Independence Law of March 11.

However, in recent years, Russia has repeatedly demonstrated that bilateral or international agreements mean nothing, as evidenced by the 2014 aggression against Ukraine and Crimea illegally ripped off and annexed to Russia, in violation of bilateral agreements, the international law and the 1994 Budapest Memorandum. In the latter, Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons in exchange for guaranteeing its territorial integrity, which Russia itself has signed.

Putin’s order does not. 355

Such an attempt to re-legitimize an illegal act in Russia, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, is not the only legal step the Kremlin has attempted in recent weeks to justify its aggressive policy in this way, be it rhetoric or ordinary military action.

More significant and important is that the document, which has already entered into force, was signed by Putin himself, and its consequences are much broader, applicable not only to historical issues, the Baltic States, but in a broader context.

Putin’s order does not. 355 “On the framework of state policy in the field of nuclear deterrence” seems, at least at first glance, an explanatory note addressed mainly to western countries and organizations such as the United States and NATO. At the same time, it is a document of strategic importance, which sets guidelines for Russia to follow and how it can proceed with respect to nuclear weapons.

Of course, such a document, even signed by Putin himself in Russia, is not necessarily the most important factor in the decision-making chain. But filling the information gap and trying to dispel Western doubts and arguments.

In recent years, the popular claim in the West that Russia has been ready for decades to pursue an escalation strategy (E2D) has been accepted almost universally both in the ideas of many experts and in government documents.

The very concept of E2D is controversial: some experts disagree with the idea that such a strategy exists or is being considered and implemented by the Kremlin.

It is more a western imagination of what and when Russia would do in case of conflict. This is the opinion of Michael Kofman, a researcher at the Naval Research Center (CNA), one of the few experts who doubts the existence of E2D in Russia.

© Youtube

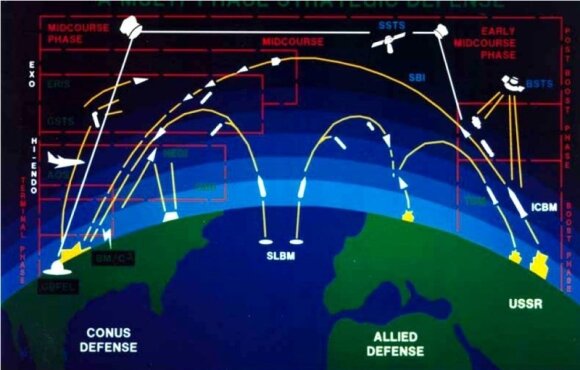

Paradoxically, E2D is derived from the work of Harvard professor influenced by the Cold War Thomas Schelling and is based on the strategy used by the Americans themselves during the Cold War, especially in the early 1980s: in the 1980s and 1990s , the Soviet Union had a great conventional advantage over NATO. invasion precisely by tactical nuclear attacks.

In modern times, when NATO already has a conventional advantage over Russia, the US USA He has included such a strategy in Russia’s official jargon in 2015, when then-Under Secretary of Defense Robert Work and Admiral James Winnefeld testified in Congress that such a strategy exists in Russia.

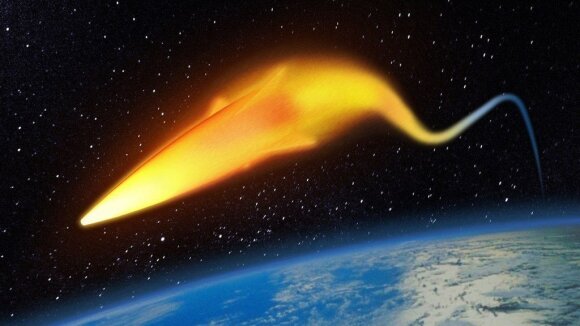

The essence of this strategy is simple: During a military conflict, the weaker side conventionally achieves its objectives by discouraging the adversary from further military action using a nuclear weapon, preferably a small power of a few to several kilotons, not necessarily directly against rivals on the battlefield but close to it, as at sea. or in a remote area.

The use of such a weapon alone would be a sign that the country is determined to repeat actions that could quickly escalate to new nuclear exchanges, perhaps even much more powerful.

Theoretically, this would work as a deterrent, but unlike classical defense based on a nuclear deterrence strategy (“if you hit me, I will use nuclear weapons against you”), that E2D strategy can also be applied aggressively: the US. USA They have repeatedly considered a scenario. Russia would launch a conventional offensive operation against the Baltic states if the Kremlin detonated a nuclear weapon over the Baltic Sea to deter NATO retaliation.

If NATO were to withdraw, the Baltic states would likely be occupied and the Alliance would be in danger of collapse, if NATO did not withdraw and respond, there would be a risk of nuclear conflict, since NATO is a nuclear alliance. Russia, for its part, has repeatedly reinforced these Western fears in its military exercises through the use of nuclear weapons: in 1999 and 2009, during Zapad’s exercise, Russia imitated the use of tactical nuclear weapons against Poland. The United States also revealed this year that it was also mimicking the limited use of nuclear weapons in military simulations.

Defense policy with strange reserves

On the other hand, Putin’s order does not. The content of 355 seems to bury this E2D strategy, because, contrary to 2014 Russia’s military doctrine, it would be difficult to see the E2D strategy, at least directly, in a document signed by the Russian leader this week.

“I often find such a declarative policy meaningless. Such documents are intentional.

ambiguous, normative and refers to a wide range of uses of nuclear weapons. No one will look at these documents in case of conflict. On the other hand, you can’t dismiss them just because you don’t like them. “They need to be analyzed more broadly, in the general context of a limited number of similar signaling documents,” said Kofman.

Nikolai Sokov, an analyst at the Vienna-based Center for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation, also told him that the new document should be welcomed, at least for further clarification.

© Photo from the Presidential Administration of Belarus

“This Putin order clearly mentions nuclear deterrence as a defensive policy: the use of nuclear weapons is left exclusively to situations where Russia is attacked, the opponent is punished.” On the other hand, this document allows a nuclear response scenario where Russia feels that its conventional forces are incapable of repelling conventional attacks. This concludes the rumors that Russia will use “offensive deterrence” as that popular scenario of aggression against the Baltic states, “Sokov wrote.

In addition, he said, the publication of the document itself and the writing of the text are eloquent signs, mainly for the United States and its NATO allies, since Putin’s order establishes more clearly than ever the list of actions that Russia considers military , policies and policies. The change in strategic position can become military (aggression) threats to Russia. And that would mean that Russia could take nuclear deterrence.

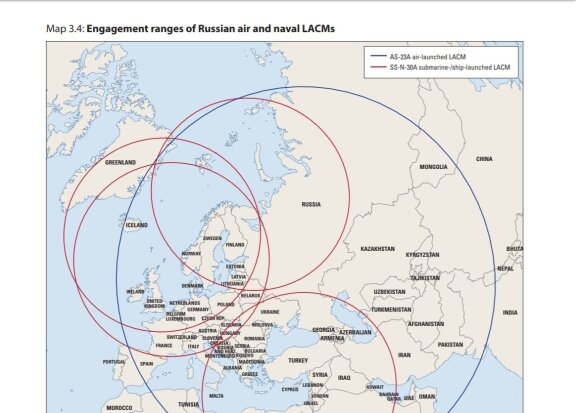

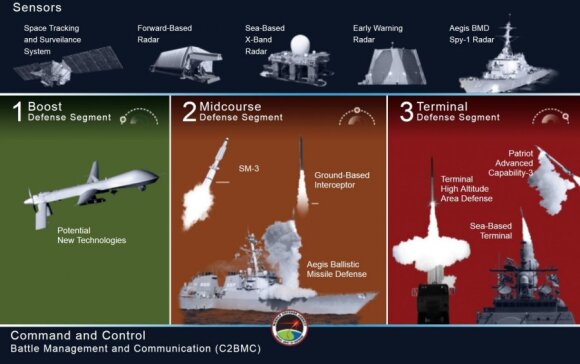

“The deployment of medium and short range anti-missile systems, cruise missiles and ballistics by states that consider RF as a potential adversary, especially non-nuclear and hypersonic weapons, combat drones and energy weapons specific “is another one of those conditions. In part, there is nothing new in that: The Kremlin has opposed the deployment of elements of the United States anti-missile shield in Europe for several years and has said that it represents a threat to Russia’s strategic forces.

© Lockheed Martin

On the other hand, the collapse of the Medium-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty last year, because of Russia, led to new redactions, namely medium-range missiles, the deployment of which was prohibited until 2019 by the INF Treaty, as well as the deployment of winged and hypersonic weapons. The latest weapons are being developed and developed by Russia itself, but NATO’s programs are seen as a threat. Your document names more.

One such threat is “the mobilization of the general-purpose forces of a potential adversary, including nuclear weapons delivery facilities, to the RF and its allies in adjacent territories and adjacent sea waters.”

In addition, the threats also explicitly include the “development and deployment of anti-missile and percussion defense systems in space”, “nuclear weapons and / or other weapons of mass destruction that could be used against the RF and / or its allies, as well as the surrender of these weapons, uncontrolled proliferation of nuclear weapons, their means of delivery, technology and equipment, “deployment of nuclear weapons and their means of transportation in non-nuclear territories.”

Anti-missile defense (www.mda.mil)

This would mean the deployment of conventional NATO forces, such as warships or aircraft capable of using nuclear weapons, near Russia’s borders. For example, the deployment of a US warship with cruise missiles in the Baltic Sea or the deployment of dual-use aircraft (capable of carrying nuclear weapons) in Poland, which has been increasingly talked about in recent months , would represent a threat to Russia. In other words, Russia is open to the idea that it must include all these capabilities in the planning of its nuclear missions in NATO countries: it is no longer the rhetoric of individual politicians, but an official order from the head of the country, the chief of the armed forces.

Identifies, but does not specify, capabilities such as “nuclear missile warning tools.” This would mean the simplest radars targeting Russia’s nuclear weapons, from flying AWACS aircraft to F-35 fighters already deployed in Lithuania, which can carry out a “missile nuclear attack warning” mission, in other words, to record the launch of the missile. It is this uncertainty that raises the most abstract questions about the capabilities of potential adversaries on the threat list.

Intentionally left ambiguities

Furthermore, even if Putin’s order does not explicitly mention the E2D strategy, according to Sokov, the document is fraught with deliberate omissions. Some of them can be evaluated in different ways.

“This Putin order clearly mentions nuclear deterrence as a defensive policy: the use of nuclear weapons is left exclusively to situations where Russia is attacked, the opponent is punished.” On the other hand, this document allows a nuclear response scenario where Russia feels that its conventional forces are incapable of repelling conventional attacks. It seems to end rumors that Russia will use “offensive deterrence” as that popular scenario of aggression against the Baltic states. On the other hand, the ambiguous wording has been preserved.

“Russia’s nuclear deterrence policy is defensive in nature and guarantees defense of state sovereignty and territorial integrity against aggression against Russia and its allies, and in the event of military conflict, prevents escalation of military action and stops it on terms favorable to Russia and its allies, “the document says. This can be interpreted in different ways.

For those who see Russia’s E2D strategy, for example, this is yet another proof that, in the event of conflict, Russia is stopping the conflict on its own terms, particularly with nuclear weapons. However, the critics’ argument is also strong: the fact that Russia tends to avoid escalating military action after the conflict “can mean a lot, but not necessarily the use of nuclear weapons.

© Wikimedia Commons

Modern surveillance tools, from human intelligence (HUMINT) to electronics (ELINT), and especially satellite capabilities, can quickly detect an opponent’s readiness to use nuclear weapons.

All the more in the case of demonstrative preparatory actions, such as the open deployment of ballistic missiles capable of transporting nuclear weapons at launch sites (where they can be regularly disguised or redeployed), such signals would not hesitate to be perceived by the enemy as hit, but that doesn’t mean where, when and if it will at all. There are more ambiguities in the document.

For example, the order establishes “unacceptable damage” to an opponent that he would receive in the event of a nuclear attack. In the classical sense, it is the language of dry numbers, but at the same time terrible: 20-25 percent. the destruction of the country’s population and half or two thirds of the industry. Even in the Russian military doctrines of 2000 and 2014, more moderate formulations were chosen.

The question of sovereignty and territorial integrity is also unclear: if Russia treats sovereignty in accordance with international law, which it did not adhere to when opening Crimea from Ukraine, what response would the Russians choose if the Ukrainians decided to claim Crimea for the force?

The same question arises whether the Kremlin regime feels threatened only by its own survival and not that of the country. In other words, if there was a threat to the cream of the summit in Moscow, but not to the state as a whole, how would the Kremlin recognize and name that threat? Is a cruise missile a sufficient threat to the response, or would it be caused by more than a few?

At the same time, even NATO’s multilateral battalions in the Baltic States and Poland can be seen in the document as a threat to Russia that could be countered by nuclear deterrence. On the other hand, by not naming NATO directly, but with a very clear allusion, such as a nuclear Alliance that threatens Russia, Russia, in his opinion, automatically turns all the Allies into legitimate nuclear targets in this order.

Being a target in itself is one thing, but the condition for a guaranteed nuclear attack is quite another. This is clearly stated in the document at first glance: Russia will react to the launching of ballistic missiles in Russia or its allies (in this case, Belarus in the first place).

© Globalsecurity.org

“But why not just ballistic missiles, or why a massive launch of cruise missiles would not provoke a nuclear response, as was thought in Soviet times? Does this mean that dual-use missiles will automatically be classified as a nuclear attack?

What does a reliable nuclear warning mean? The examples from 1983 and 1995, when Russian early warning systems erroneously indicated the launching of enemy missiles, confirm that there may be erroneous signals. Does the Russian political and military leadership have any guarantee that these mistakes will not happen again? N. Sokov asked.

In his opinion, despite the fact that the document precisely emphasizes the importance of a nuclear deterrent rather than a war strategy, the remaining uncertainties create a new space for speculation.

One of them is the role of China. China is now an ally of Russia, on which the Kremlin increasingly depends each year and is already falling behind in the conventional sense.

However, the document also makes clear that Russia’s nuclear deterrence on “peaceful countries that view the Russian Federation as a potential rival” applies to both the United States and Lithuania, but not to a “strategic partner”, China.

“But at the same time, it may not be a very subtle warning to China that if it changes its policy towards Russia, it will join NATO as a legitimate nuclear deterrence target,” Sokov said.

It is strictly prohibited to use the information published by DELFI on other websites, in the media or elsewhere, or to distribute our material in any way without consent, and if consent has been obtained, DELFI must be cited as the source.

[ad_2]