[ad_1]

The nature of the beggars’ activity contradicts the essence of the true workshops of the industrial artisan organizations of the late Middle Ages and early Modern Ages.

The social organization of Vilnius beggars is a specific social structure characteristic of the social map of Vilnius and Lithuania.

Medieval beggars – “Cashiers of God”

Modern historical science pays much attention to those who have been disadvantaged by life, who have experienced social exclusion: various marginalized strata, which researchers call “marginalized people”, “marginalized” and the like.

There are about 200 such groups. At the beginning of the modern age, their numbers increased as the degree of social differentiation, exclusion and marginalization increased.

The production of workshops, the structural crisis of society, wars and plague epidemics have enormously increased the number of “strangers among them” (especially beggars and tramps). Then they accounted for about 5-10 percent. All society.

The number of these margins was determined by place and time. Beggars, unlike vagrants, were classified as revered poor, giving alms to the poor in Catholic society, an expression of Christian love for neighbor.

Following the example of Christ, the hierarchs of the Church washed the feet of the beggars on Good Thursday and Good Friday. This ritual was also practiced by the bishops of old Vilnius.

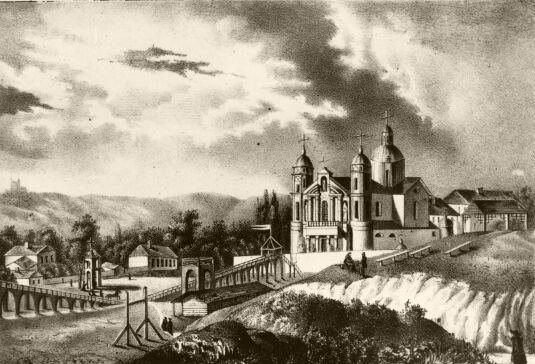

Vilnius County Archive Photo / Vilnius St. Church of the Apostles Peter and Paul in the 19th century.

Thus, positive margins (beggars) were visuomen necessary for society.

Beggars were created for a variety of reasons, but primarily due to poverty. Not for nothing are they called synonymous with “poor” due to physical and mental disabilities, domestic violence and old age.

Due to their way of life (living on the street and sometimes in a shelter), activities (begging in public places, near churches, squares, streets), beggars were the most visible representatives of the society of poverty .

They come from rural and urban areas, from different social strata: peasants, settlers and nobles, in terms of gender and age, but they are mainly concentrated in large cities.

Thus, in Vilnius, where there were the largest beggars, the possibility of obtaining refuge and a lower level of control.

There were many funerals for Church leaders, nobles, or wealthy city dwellers. And during each of these celebrations, in order to atone for the sins of the deceased or gain prestige, considerable sums were distributed among the beggars.

Inventions in the fight against social ills

Despite their borderline position on the city’s social map, the beggars were clearly visible. As part of society fell into poverty, the number of beggars increased.

Churches, state and municipal authorities have faced serious begging problems. Although the Church exercised social welfare, promoted charity, and established shelters, the problems did not diminish.

In many European countries, the establishment of forced correctional (labor) houses for beggars was initiated, and alms were given on purpose.

Various corporations, including fringe ones, are known to have created forms of self-government.

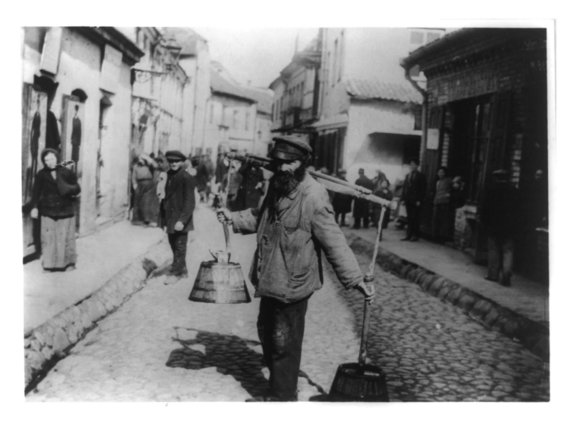

Photo from Vida Press / Water carrier in Vilnius in the 20th century. at first

It was in the Middle Ages when the presence of beggars was sanctioned with the approval of special corporations such as the blind. According to some authors, until the 18th century. pab. In Rome, Italy, there was a joint organization of beggars that defended the interests of its members.

In Poland and Lithuania, changes in solving the problems of begging can only be seen in the 18th century. at the end of the 19th century, when he realized that begging was influenced by the state of the economy and unemployment in the country.

Until then, urban bureaucrats first looked for ways to reduce the number of beggars, to control them, to make the beggars themselves more “civilized.”

State and municipal governments sought to limit the number of beggars, defend their own, and expel strangers.

In the largest city of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Vilnius, in 1636. it was established and until 1784. there was a peculiar organization of beggars, reflecting the original mixture of beggars’ self-government and control of the city government.

The statute of the fraternity was not adopted by the beggars but by the city authorities. The privilege clearly states that, seeing great disagreements between the beggars, the city authorities wrote an order for them in Polish and asked the ruler to approve it.

The city authorities asked the ruler to exempt the beggar’s room (gospod) from the obligation to accommodate guests. On the extent of begging in Vilnius in the 17th century. I p. one can only guess, but the problem was acute.

At that time, there were several wealthy and educated people in the city government. Perhaps it was the vait with the annual council who came up with the idea of giving beggars some autonomy, reserving the right to control it, pursuing a higher order of begging, and ensuring that the religious needs of the beggars were met.

At least initially, it had to operate under the supervision of city authorities. Proof of this is that in the first stage of its activity the fraternity operated under the direction of S. Ancients towers of the Church of Nicodemus and Joseph.

And both the church and the hospital were governed by the city government: she appointed a pastor, a provisional of the hospital. The city officials who drew up the fraternity bylaws were better acquainted with the craftsmen’s guilds and the merchant’s guilds, so they made the poor fraternities according to a common “template,” because it fit the bill perfectly.

Furthermore, the provisions reflect rather medieval tendencies for self-government rather than the spread of beggarly repression typical of modern times.

Beggar’s customs

The poor on the beggar list had to choose to meet once a month (and pay a penny each time) in a house with a citizen.

In such a house there was a “gaspada”, a room where a brotherly chest with stored money was stored. The keys to the chest belonged to the “old man of the church” and the “old man of the street.”

The owner of the house had to be the judge and take first place in the meetings. Together with the elders, he had to choose 4 botanists to chase the supposed beggars out of town, punishing the perpetrators.

The fraternity had a secretary who understood Latin; newcomers were said to bring such letters.

The owner of Gaspada had to be “Magdeburg”, that is, under the jurisdiction of the city government, not the church or the land. Yes, apparently, the intention was to ensure that the fraternity headquarters remained under the jurisdiction of the city.

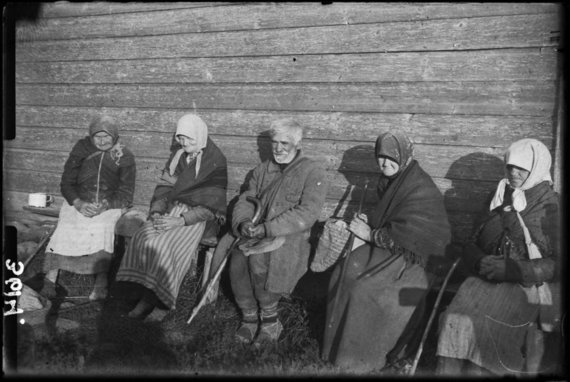

Photo by Jurgis Dovydaitis / National Museum of Art MKČiurlionis / A group of beggars ready to travel to St. Rocks Concessions, 1932

The poor who had no place to stay had to be transported to St. The Spitol of Nicodemus and Joseph, and two annual Masses for the living and dead benefactors were to take place at St. John’s Parish.

There is no data on how the fraternity regulations were implemented. One could speculate that they were initially observed, although such a natural element was difficult to discipline.

Many beggars (“suitors”) did not want to belong to the fraternity and pay taxes. Late eighteenth century data, this organization did not cope with the supervision of the growing number of beggars.

The authorities did not realize or did not want to realize that the scale of begging was increasing for economic and social reasons, and they wanted to solve the problems through punishment and forced labor.

Originally a secular organization, since the 18th century. By the end of the first trimester she became more religious. This was reflected in the subordination of this fraternity to S. Al pastor of the Church of San Juan.

But in essence, the Vilnius Beggars Brotherhood was a specific form of organization of the marginal social group of the city’s society, not identical to either the workshop or the ecclesiastical fraternity.

This text is part of the project “History of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania”. Find more historical texts on the page ldkistorija.lt

[ad_2]