[ad_1]

Wilhelm Brasse, son of Poland and Germany, went down in history as a photographer at Auschwitz. How does it feel to photograph the torture of prisoners like you on a daily basis? He didn’t tell about his feelings later …

A concentration camp needed a photographer

Wilhelm Brasse learned to take pictures in his aunt’s photography studio in Katowice. There the young man gained practice. It was very successful, the customers were satisfied: in the photos they looked natural, without stretching. And he communicated with visitors in a very helpful way, writes dailymail.co.uk.

Osvencimas

When the Nazis occupied southern Poland, Wilhelm was in his early twenties. The German army badly needed strong and healthy young men. The Nazis demanded that Wilhelm, like some of his countrymen, swear allegiance to Hitler, but the guy flatly refused. Wilhelm was beaten and spent several months in prison, and when he left, he decided to flee the country.

Wilhelm was caught trying to cross the border between Poland and Hungary. He was taken to a concentration camp and half a year later, the prisoner’s fate changed in an unexpected direction.

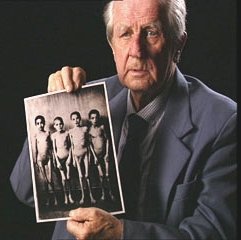

At Auschwitz, the Nazis noted that he was fluent in German. Upon learning that he was working as a photographer, he was sent to the Auschwitz Forensic and Identification Department. Wilhelm and four other prisoners, who also had photographic skills, were asked to take several photographs. The young man easily coped with this task and also had experience working in a photographic laboratory.

Realizing this, the Nazis decided to assign him to the forensic department to photograph the incoming prisoners. From that day on, he became a full-time photographer for Auschwitz.

Wilhelma bream

After a time, W. Brasse met Josef Mengele, a doctor with sadistic tendencies, who personally inspected newly arrived prisoners and selected from them those he needed for tests. Mr. Mengele informed the photographer that from now on he would also photograph medical experiments on humans.

W. Brasse photographed the cruel attempts of a German doctor, as well as the sterilization operations of Jewish girls and women prisoners, which were carried out by a Jewish doctor (the same prisoner as W. Brasse) on the orders of the Nazis.

In general, women did not survive such operations.

Wilhelmas bream

“I knew they were going to die, but I couldn’t tell them that when they photographed me,” sighed the photographer, remembering his work many years later.

Very often, Wilhelm also had to photograph Nazi officials responsible for tens of thousands of deaths. Superiors needed photos for documents or just personal photos that they sent to their wives. And every time the prisoner repeated to them: “Sit comfortably, relax, look freely into the lens, thinking of your homeland.” As if the action took place in a photographic studio. I wonder what words he would say to the prisoners he photographed.

The Nazis highly appreciated the work of W. Brasse and sometimes gave him products and cigarettes. He did not give up.

During all the time he worked in the concentration camp, W. Brasse took tens of thousands of photos, terrible, shocking, incomprehensible for a healthy person. The flow of prisoners did not continue. On a daily basis, Mr. Brasse took so many photographs that a special group of prisoners met to select them. It is shocking how pedantic and cynical sadists documented all their atrocities.

But what did the photographer feel when capturing them?

Wilhelmas bream

© Wikimedia Commons

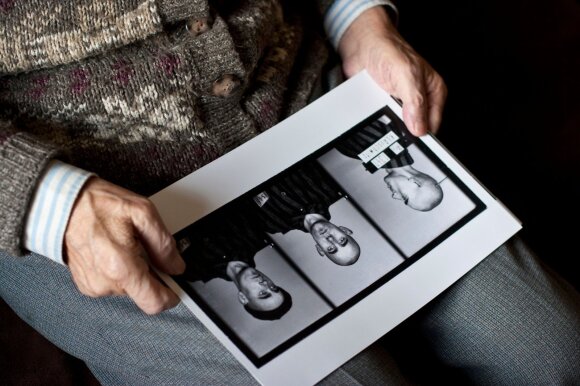

As W. Brasse later recalled, his heart ached every time he was photographed. He was ashamed of these mortally frightened people, and it was very unfortunate for them, and his conscience was pained that imminent death awaited them, and he would go to rest after the day’s work. But he was no less afraid of the Nazis, he was afraid he would not listen to them.

Could Mr. Brasse have renounced those “duties” and was he morally correct in agreeing to do such work? Basically, he only had one option: listen to Nazi orders or die. He chose the first option and left thousands of documented evidence of savage crimes in history. But it tormented him and tormented him until the end of days.

“The photographs I took in Auschwitz haunt me constantly,” the postwar photographer admitted to the press on several occasions. It was especially difficult for him to remember photographing one of the most famous Nazi experiments with Cyclone-B, which killed at least eight hundred Poles and Russians in Block 11.

And yet he could not forget the face of the frightened Polish girl with an amputated lip: Czesława Kwoka died immediately after the photo session: a camp doctor injected her with a lethal injection into her heart.

Czesław Kwok

© Wikimedia Commons

“Prendí fuego a los negativos bajo la supervisión del jefe nazi, y cuando se fue, los llené rápidamente de agua”, recordó Brasse muchos años después.

En el Museo de Auschwitz-Birkenau se encuentran ahora documentos únicos que prueban inequívocamente el alcance total de los crímenes de la administración del campo de concentración.

La vida después de Auschwitz

El fotógrafo cautivo perdió de vista la liberación de los prisioneros de Auschwitz: fue enviado a otro campo de concentración de Mauthausen. En el momento de 1945. el campo fue liberado por los estadounidenses en mayo, W. Brasse estaba terriblemente exhausto, milagrosamente no muriendo de hambre.

Después de la guerra se casó, tuvo hijos, nietos. Hasta el final de sus días, un ex fotógrafo de un campo de concentración vivió en Zywiec, Polonia.

Al principio, W. Brasse intentó volver a su profesión anterior, quería hacer retratos, pero se dio cuenta de que no podía. Brasse admitió que cada vez que miraba a la lente, imágenes del pasado aparecían ante sus ojos: niñas judías condenadas a la tortura y la muerte.

Los duros recuerdos no abandonaron a Wilhelm Brasse hasta su muerte. Murió a los 94 años y se los llevó.

Está estrictamente prohibido utilizar la información publicada por DELFI en otros sitios web, en los medios de comunicación o en otros lugares, o distribuir nuestro material en cualquier forma sin consentimiento, y si se ha obtenido el consentimiento, es necesario indicar a DELFI como la fuente.

[ad_2]