[ad_1]

Automatics had a special place in the history of ancient Greek technology, constituting a special, different and certainly impressive element of the scientific demon of our ancestors.

Heron Alexandreus gave us various descriptions of these robes in his “Automation”, as did the second great Alexandrian engineer, Philo the Byzantine (“Mechanical Retreat”).

The word “automatic”, however, has its origin in Homer. It is mentioned many times in the Iliad, especially when it comes to Hephaestus, the technologist and blacksmith god:

“What twenty artisans did he use to make one-legged tripods.” Malamatenia wheels were suitable for everyone at the bottom, with the gods alone in the gathering to enter and return to their home, to confuse your mind! “( Rhapsody S 376).

But also below (S 417): “And they ran to her side to raise the golden queen, two unchanged with live girls; awakening and words and strength, they also have them, and even the immortal gods taught them all the feminine art. And now they were willingly raising their king, and he in Thetis, with difficulty, sits on a star-studded throne. “

But also in the Odyssey or Hostage tells us about the automatic ships of the Phaeacians (I 558): “Why do we, the Phaeacians, not put captains or helmets on our ships, like the ships on other ships; they find what we want, only what we want, and of all the peoples who know the fields and fertile states, fasted from the sea, they pierce their loins wrapped in clouds and darkness, and they are not afraid of ever sinking or suffering harm ”.

These, of course, belong to mythology. They may have just been mythical high-tech visions. Herodotus also tells us about the statues of automobiles (nervous spasms) that the Egyptians made.

But the ancients had real automata in their society. We know of Archytas’ automatic pigeon, the automated mechanisms in theaters, the Aeolus sphere and the famous automatic Philo maiden, the first functional robot in history.

We also know about Ktisivi’s hydraulic clock, a true miracle of automation with continuous operation without human intervention, about Dionysios’s automatic catapult (machine gun), about the (automatic) magic fountain and much more.

Even the automatic opening of doors in the temples after the sacrifices had the Ancient greece, in what is considered the first building automation in human history.

And so fatally the discussion about Talos, the mythological guardian of Crete, centers on whether it was just fantasy or if it had some dose of reality.

How advanced technology could the Greeks have had that allowed them to build not just robotic soldiers, but giant war machines that functioned autonomously?

Something like early artificial intelligence …

What was Talos

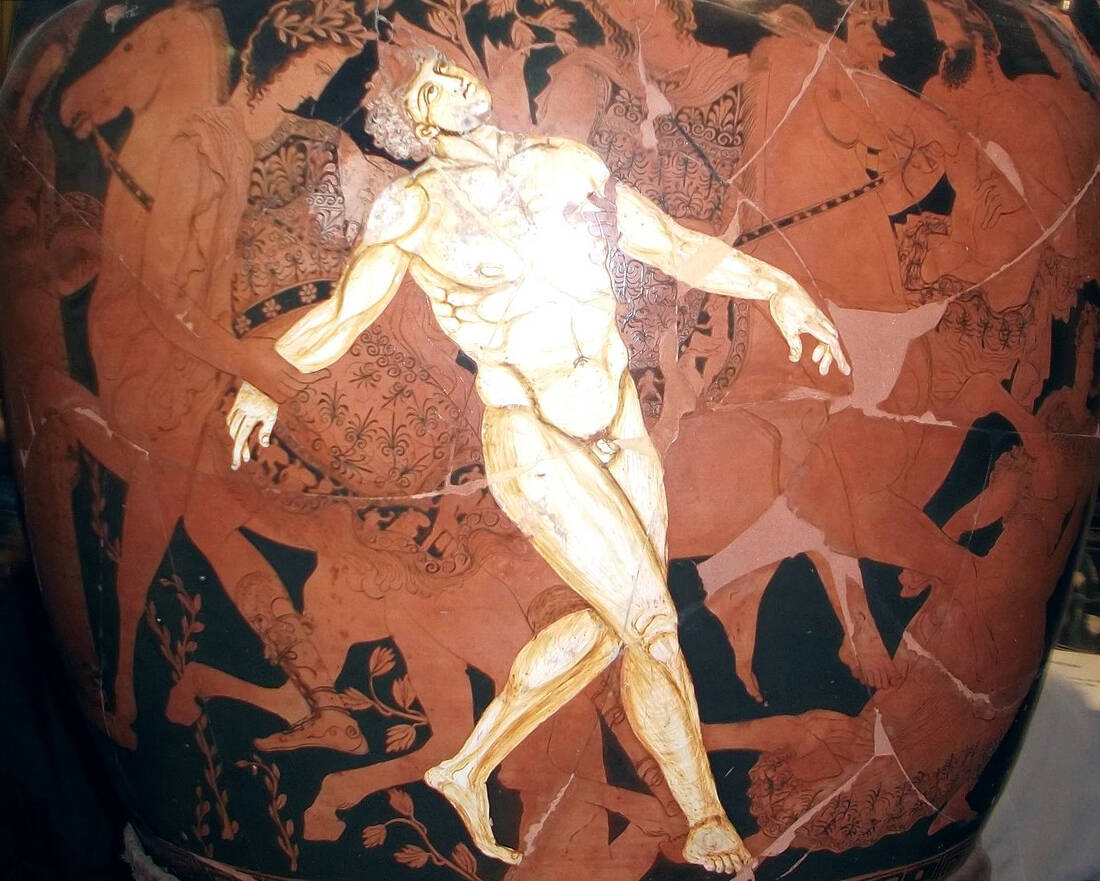

It was huge, anthropomorphic and with a body made of copper. The ancient descriptions describe it in terms that today we would attribute to robots.

And it is in fact in ancient Greek mythology that we find the first descriptions of a mechanical humanoid. A story associated with the Argonaut Campaign, though by no means limited there.

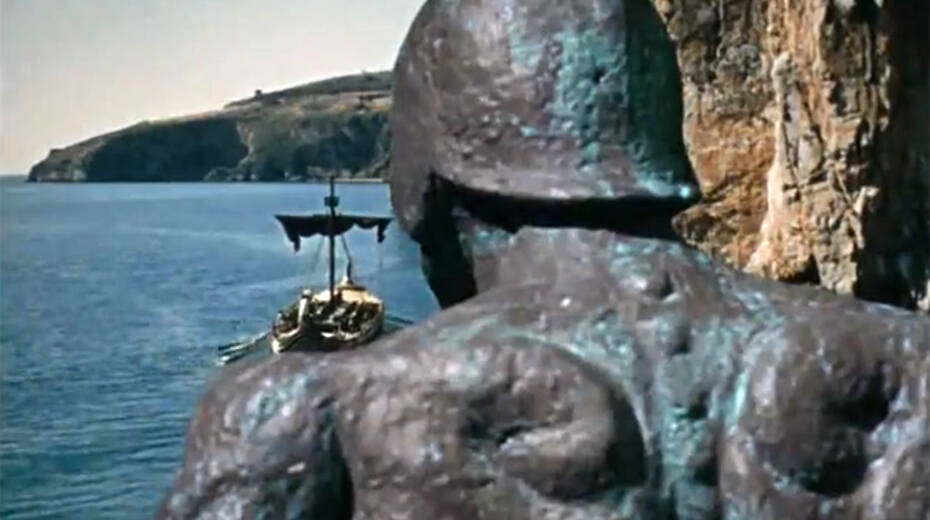

What was this giant automatic bronze that the Argonauts found in Crete that was made to look like a human? The guardian of the island, who plowed the beaches and threw huge rocks at enemy or unknown ships.

There are different versions in Greek mythology about its origin. And they all describe it in detail and vividly. Apollodorus tells us in his four-volume “Library” that it was a work of Hephaestus, a gift to Minos to protect Crete of the attacks.

Plato wants him to be a real person and claims that he was the brother of Radamanthis and Minos, another son of Zeus and Europa. Like his brothers, he was raised by Asterion, the mythical king of Crete, to whom Zeus entrusted Europe.

Apollonius of Rhodes tells us something different in his “Argonauts”. Talos, in this version, was a gift from Zeus to Europa, who then gave it to his son Minos.

Isychios Alexandreus believes that Talos must have been an ancient solar deity, as “talis” meant “sun”, while “Talaios” was the name by which Zeus was known in Crete.

Whatever its origin, the Plato He assures us that the hero was in charge of supervising the implementation of the law on the island. That is why he always seemed to carry with him the laws of Crete written on bronze plates.

Most sources agree that he was the island’s insomniac guardian, circling Crete three times a day to monitor its shores. There are also ancient testimonies that show it winged. The wings have only been shown to give a sense of proportion. It is not easy to walk around Crete three times a day.

Either from land or from the air, Talos threw stones at the unknown ships, to keep them off the shores.

Others claim that he was the last descendant of an ancient tribe of bronze men. Ancient Greek mythology spoke of the Genesis of humans, stages of human presence on Earth.

THE Hesiod and Ovid recognizes five (gold, silver, bronze, heroic, and iron). Talos belonged to the third. The people of the Bronze Age were cruel and strong, creations of Zeus from the ashes. They brought bronze armor, bronze weapons, and lived in copper houses.

Those who did not die from the mutilation, as they were very violent, were lost in the Deluge of Deucalion. Finally there is another acceptance that wants Talos to be the work of Daedalus.

Talos kept the unknown ships approaching Crete at bay by hurling huge stones at them. In fact, if he saw people on Cretan soil, he would burn them with his hot breath or burn their bronze body in fire and hug them tightly.

This deadly embrace, legend tells us, consumed the invaders. Their corpses were found by the Minoans with their mouths open, having witnessed the pain and horror. Talos laughed after each triumph.

In addition to monitoring the coasts, he toured the Cretan settlements three times a year to see if the laws were being obeyed. That is to say, what these copper plates wrote that he carried on his back.

Talos appeared on a series of coins. Phaestos and he was generally portrayed as a young, naked man with wings on his shoulders. This is what at least the representations of the coins that were removed from the Minoan palaces want.

How he died

According to Greek mythology, Talos met his end when the Argonauts landed on Crete, returning from Colchis.

Jason and his men moored on the island and were forced to confront the bronze giant, who tried to keep them at a safe distance from his rocks.

And they certainly wouldn’t have been able to deal with him if they didn’t. Medea in Argo, who charmed him with his words. The moment he was promised eternal immortality, Jason managed to pull out his heel nail.

It was the cap of the giant’s only vein, starting from the neck and ending at the ankles. His ichor, the golden blood of the gods, was shed from his body and he died.

The mighty giant collapsed like a log on the Cretan beach. The Argonauts celebrated their victory, equipped themselves with the necessary equipment, and set out for Iolkos.

In a second version he was also killed by Argonautis Poias, son of Thavmakos of Magnesia and father of Philoctetes, hitting him with an arrow in the same a. The only vulnerable part of her body.

What could have been

However, as historians of technology have suggested, Talos was not another paradox of Greek mythology. Something just strange in this particular universe of gods and heroes.

It has been argued, for example, that Talos symbolized the power of copper during the Greek Bronze Age (3200-1200 BC), that is, the passage from stone to bronze.

Its enormous size is perhaps a metaphor for what skilled boilermakers could do, for how large and sophisticated constructions showed the military superiority of copper as a weapon.

After all, we are on top of bronze. technology and the military power of nations was measured in terms of metallurgy.

As for its destruction, historians insist it was perhaps another transition story from copper to iron now. In the 12th century BC we also have the Descent of the Dorians and the end of the Late Helladic Period, with the decline of the Mycenaean world.

It is not ruled out that the Greek tribes that descended from the north had weapons of iron and this alternation of copper to the new and stronger metal mythologically endorsed the loss of Talos. His death was also the end of the superiority of copper.

Of course, in addition to its symbolic function, Talos was something completely unique and special, even in terms of modern culture. It was the very embodiment of technological superiority, what man could achieve if he turned his mind in that direction.

As the classical history teacher Merlin Peris tells us in his work “Talos and Daedalus” (1971), Talos was the first robot of the world. “Talos was remarkably futuristic,” continues the scholar, “symbolizing the scientific potential of the time.”

Talos stands as one and only in world mythology. A powerful humanoid robot, a mechanical giant far ahead of its time …

[ad_2]