Just below the frozen Antarctic ice shelves, the researchers discovered a gas leak that could change the region’s climate fate.

For the first time, scientists have detected an active leakage of methane gas, a greenhouse gases with 25 times more potential for global warming than carbon dioxide, in Antarctic waters. While underwater methane leaks have been previously detected worldwide, hungry microbes help keep that leak under control by gobbling up the gas before it can escape too far into the atmosphere. But according to a study published on July 22 in the magazine Proceedings of the Royal Society B that doesn’t seem to be the case in Antarctica .

The study authors found that it took about five years for the microbes that ate methane to respond to the Antarctic leak, and even then they did not completely consume the gas. According to lead study author Andrew Thurber, the underwater leak almost certainly sent methane gas into the atmosphere in those five years, a phenomenon that current climate models do not account for when predicting the extent of future global warming.

“The delay [in methane consumption] is the most important finding, “Thurber, a marine ecologist at Oregon State University, he told the Guardian . “It is not good news.”

Methane is a by-product of ancient decomposing matter buried below the seafloor or trapped in polar permafrost. Climate change it is already causing some of the permafrost to melt, slowly releasing vast reserves of greenhouse gases underground. However, the impacts of underwater methane leaks remain poorly studied, especially in inhospitable Antarctica, simply because they are difficult to find, Thurber said.

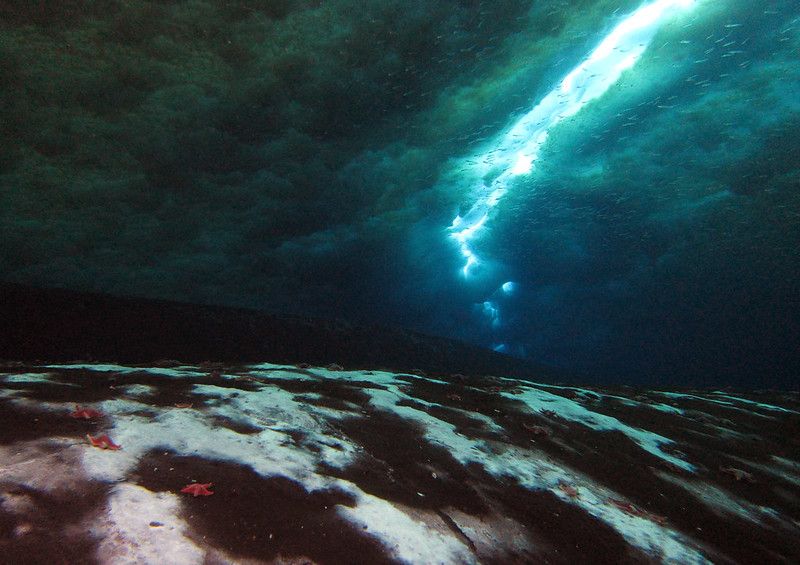

The recent leak, located some 30 feet (10 meters) below the Ross Sea, near the Ross Antarctic Ice Shelf of southern Antarctica, was discovered by chance when civilian divers swam in 2011. When Thurber and his colleagues visited the site later that year, the seafloor showed telltale signs of a methane leak: white “mats” of microorganisms that exist in a symbiotic relationship with methane-consuming microbes spread out in a 200-foot-long (70m) line to along the sea floor.

A sediment analysis confirmed the obvious: methane was leaking below the sea floor. When the team returned to the site five years later, more microbes appeared, but the methane continued to flow. Thurber called the discovery “incredibly troubling,” since most climate models feature bacteria that feed on methane to eliminate this underwater threat almost immediately. This slow microbial response, coupled with the shallow depth of the leak, suggests that significant amounts of methane have been dumping into the atmosphere over the Ross Sea for years.

Generally speaking, this is just a small leak, and it probably won’t tilt the climatic scales significantly. But the waters around the southern continent may contain up to 25% of Earth’s marine methane, and more leaks may be happening right now without anyone knowing. According to the researchers, understanding how Antarctica’s undersea greenhouse gas stores interact with the ocean and the atmosphere could have huge implications for the accuracy of climate models, now the trick is to find and study more of them while our models still matter.

VIDEO

Originally published in Live Science.