[ad_1]

Background characteristics of the mother and children included in the TDHS 2005-2015

Approximately 37,205 pairs of children and mothers were drawn from the TDHS from 1991 to 2015. Table 3 presents the background characteristics of the pairs of mothers and children included in the recent surveys from 2005 to 2015. Most of the children included ~ 50% they were girls. Approximately one third (~ 30%) of the children were older than 35 months, followed by 6 to 23 months. Most of the children (about 45–50%) were of normal birth weight, just under 4% were under normal birth weight, and some did not report their birth weight (~ 30–50%). Over 70% of all children were recorded as living in rural areas for all surveys. Less than 20% of the children sampled had diarrhea and / or fever symptoms in the 2 weeks prior to the survey.

Among mothers, more than half were between the ages of 25 and 39. The proportion of mothers without formal education had decreased from 27% in 2004-05 to 21% in 2015-2016. However, in the same period, the proportion of mothers who obtained higher education after primary school remained the same. Some of them started breastfeeding within an hour after birth, however, the proportion decreased from 55.5% to 37.5% in 10 years. The proportion of mothers who gave birth before the age of 15 had decreased slightly from 3.5% in 2005 to 2.5% in 2015. Furthermore, the proportion of mothers with three or more children fell from 13.1% in 2005 to 11.5% in 2015. According to their nutritional status, the proportion of underweight mothers (<18.5 kg / mtwo) decreased slightly from 8.8% in 2005 to 7.2% in 2015, while the proportion of obesity more than doubled from 3.8% to 8.2%. In all surveys, the share of the richest households, ranked according to the wealth index, ranged below 15%, while the poorest households exceeded 20%. In general, most households are headed by men and by people between the ages of 30 and 49 (Table 3).

Prevalence and trends of anthropometric failure (1991-2015)

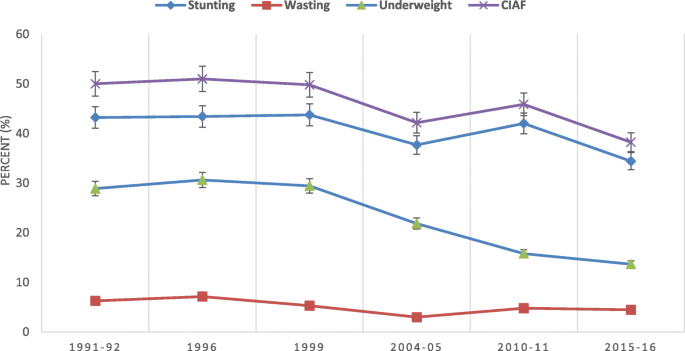

Figure 1 shows trends in the prevalence of CIAF and conventional rates of stunting (ZAT <-2DE), wasting (WHZ <-2DE), and underweight (WAZ <-2DE) from 1991 to 2015 in Tanzania. This analysis observed a significant decreasing trend of anthropometric failure over the last 25 years in Tanzania (P<0.001). In 1991, approximately half (50%) of the children surveyed had anthropometric defects compared to one in three (38.2%) in 2015. Similarly, for wasting, stunting, and underweight (P<0.001). However, during 2005–2010 the prevalence of stunting and wasting and CIAF worsened slightly. In 1991, approximately half (50%) of the children surveyed did not have any type of anthropometric failure (Group A); while more than half (62%) of the children did not present anthropometric faults in 2015 (Table 2). The prevalence of children with multiple anthropometric failures (Group D) decreased significantly from 2.2 to 1.5% over two and a half decades (P<0.001), however, it worsened slightly in 1996 (3.2%) and 1999 (2.7%). On the other hand, the prevalence of stunted children only (Group F) changes disproportionately from 1991 (20.1%) to 2015 (23.2%). The prevalence of children with wasting only (Group B) leaned significantly from 1.1 to 1.6%; meanwhile, the proportion of underweight children only (Group Y) decreased significantly from 3 to 0.9% from 1991 to 2015.

Trends in the prevalence of undernutrition in Tanzania according to the CIAF classification and the conventional indices of stunting (ZAT <-2DE), wasting (WHZ <-2DE) and underweight (WAZ <-2DE) from 1991 to 2015 . P-values of the trend in stunting (X2 = 267.42, P<0.001); wasteX2 = 117.73, P<0.001); under weightX2 = 988.89, P <0.001) and CIAF (X 2 = 413.67, P<0.001).

Factors associated with anthropometric failure (2005-2015)

Table 4 presents the results of the univariate and multivariate Poisson regression analysis using TDHS data from 2005, 2010 and 2015. In the multivariate model, the place of residence, the mother’s BMI, the age of the head of household, were associated the marriage status of the mother, the education of the mother, the wealth status, the birth weight, the age and sex of the children, diarrhea, fever symptoms and the place of delivery. with anthropometric failure in several years.

The prevalence of anthropometric failure for rural children increased significantly (APR = 1.11, 95% CI, 1.01-1.21, P= 0.028) in 2015. The prevalence of having anthropometric failure decreased significantly based on the increase in the mother’s BMI. In 2015, the prevalence was lower when the mothers were normal (APR = 0.86, 95% CI, 0.79-0.95, p =0.001), overweight (TAE = 0.79, 95% CI, 0.71-0.88, P<0.001) or obese (APR = 0.65, 95% CI, 0.56-0.76, P<0.001) compared to underweight mothers. This result shows that the prevalence of anthropometric failure was reduced among married mothers compared to single mothers in 2015 (APR = 0.84, 95% CI, 0.74-0.96, P= 0.008). The prevalence was also reduced if the age of the head of household was between 30 and 49 years (APR = 0.92, 95% CI, 0.85 to 0.98, P= 0.015) and over 50 years (APR = 0.85, 95% CI, 0.78-0.92, P<0.001) compared to a younger age of 15-29 years in 2015. Additionally, household wealth status was strongly associated with anthropometric failure in all years. In 2015, the results show that the prevalence of anthropometric failures decreased significantly from the poorest to the richest families (APR = 0.86, 95% CI, 0.79–0.94, P= 0.002) and the richest families (APR = 0.74, 95% CI, 0.64-0.84, P<0.001). Mothers with a higher level of education showed a lower prevalence of anthropometric failure (APR = 0.43, 95% CI, 0.23-0.82, P= 0.009) compared to mothers with no formal education in 2015.

Both the age and sex of the children are associated with anthropometric failure in all years. The prevalence of anthropometric failure increased in children between 6 and 23 months (APR = 1.48, 95% CI, 1.31-1.67, P<0.001), 24 to 35 months (APR = 1.86, 95% CI, 1.64 to 2.11, P<0.001) and more than 35 months (APR = 1.59, 95% CI, 1.40-1.81, P<0.001) compared to boys under 6 months in 2015. Girls have a comparatively lower prevalence of anthropometric failure than boys in 2015 (APR = 0.87, 95% CI, 0.83-0.92 , P<0.001). Birth weight was significantly associated with anthropometric failure in all surveys. Compared to normal birth weight, children with low birth weight had a higher prevalence of anthropometric failure in 2015 (APR = 1.65, 95% CI, 1.48-1.82, P<0.001). In terms of illness, they both have diarrhea (APR = 1.12, 95% CI, 1.04-1.20, P= 0.002) and fever (APR = 1.08, 95% CI, 1.02-1.15, P= 0.008) were associated with a higher prevalence of anthropometric failure in 2005 and 2015 (APR = 1.07, 1.0-1.14, 95% CI, p =0.044). Furthermore, the prevalence of anthropometric insufficiency was significantly higher for children who were born at home than those who were in health centers in 2005 (APR = 1.16, 95% CI, 1.06-1.27, P= 0.001) (Table 4). However, subgroup analysis of children aged 6 to 23 months revealed that the consumption of a diversified diet was not associated with anthropometric failure (P> 0.05) in any survey as shown in Table 5.