[ad_1]

We all wonder how COVID-19 will end. We probably won’t go back to normal without a widely distributed vaccine, which is a vigorous proposition. It is also becoming increasingly clear that we will have to find a way to track the transmission and perhaps even enforce individual quarantines in the meantime.

I want to say that I am not an epidemiologist, nor am I a public health official. As a faculty member within Brock University’s Center for Digital Humanities, my role is to communicate the social and cultural consequences of digital media, including the potential privacy and security risks of software used to limit the effects of COVID-19 .

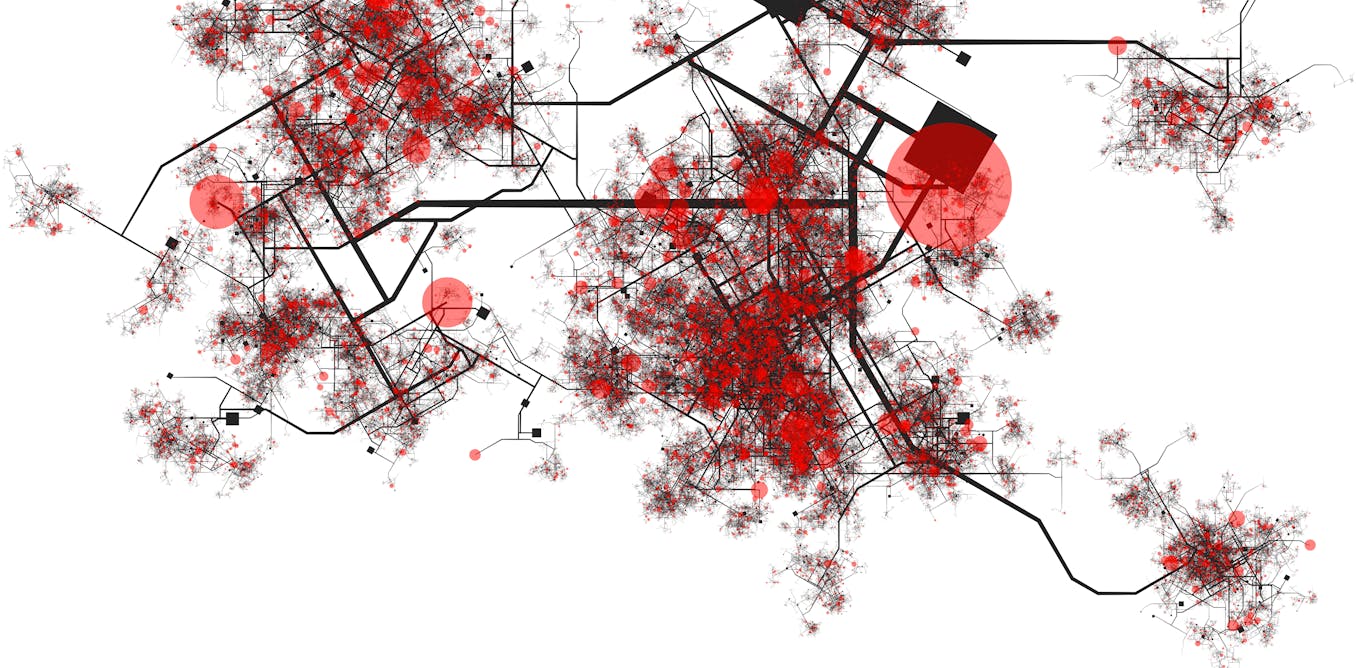

In the coming weeks and months, I hope we will hear a lot about “contact tracing”. Tracking contacts involves interviewing patients to collect information about all the people they have had contact with and all the places they have been. It is laborious and error prone because it depends on memory, interviews, and detective work.

Due to the contact tracking scale required for COVID-19, the use of cell phones to detect and record proximity seems to be an ideal solution. The Canadian government is exploring the search for contacts and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said “all options are on the table.”

Civil liberties in crisis

Before the Canadian government makes decisions that infringe civil liberties through widespread digital surveillance, we must think about the concessions we make during a time of crisis. Crises have long been used by governments and corporations as an opportunity to infringe civil liberties in the name of public safety.

We just have to think about legislative overreach in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks. In the United States, the extraordinary powers granted by the Patriot Act were revealed by whistleblower Edward Snowden when he revealed NSA and CIA surveillance. Those revelations shook the country to the core. In Canada, General Bill C-36, which contained the Anti-Terrorism Act, was passed.

During the post-9/11 period, Canadians learned a lot about phone tracking. In 2017, the Canadian government introduced Bill C-59, which amended the previous Anti-Terrorism Act and recognized past legislative hype.

Digital tracking of contacts represents an opportunity to fight COVID-19 and reopen the economy, but its implementation will create an unprecedented surveillance infrastructure beyond anything we’ve seen before.

There is an application for that

In recent days, the federal government has indicated that the provinces will be responsible for administering their plans to reopen their economies, resulting in a mosaic of contact tracking applications across the country. There is a risk that such a network of collection policies, laws and techniques will cloud COVID-19 data at the national level.

In contrast, many countries have turned to nationally required mobile applications to automate contact tracking. South Korea, Singapore, Germany, and China have implemented their own digital tools to assist public health officials and track the spread of COVID-19.

There are several models that Canadians can think about regarding contact tracking applications. China first dealt with this problem and chose some rather extraordinary methods. Citizens were allowed to travel between checkpoints based on an application integrated into online payment systems like Alipay from Alibaba or WeChat from Tencent. Without a green QR code, citizens were not allowed to travel and could face arrest for violations.

Currently, the Canada COVID-19 app, a partnership between private healthcare software company Thrive Health and Health Canada, allows you to volunteer your location data and self-report symptoms. This voluntary approach was spearheaded by Singapore’s TraceTogether app, which goes a step further by accessing Bluetooth radio on smartphones to detect proximity.

The limitations of the TraceTogether app include the difficulty of running an app 24 hours a day, which drains battery life and results in less reliable data.

The Alberta provincial government has recently launched the ABTraceTogether app; It is unclear how effective this system will be in the province.

Because the use of digital contact tracking was intended to correct interview errors and human memory, the partnership between Google and Apple has drawn enormous attention. In this case, our phones would eventually detect proximity and duration using a low-level operating system process that would allow 24/7 tracking.

The security and privacy implications are profound.

Regardless of the optimism of tech news watchers, these systems are too complex and lack the transparency necessary for lawmakers to make adequately informed decisions about their implementation.

There is no reason why the general public should trust these corporations not to monetize this system and maintain this surveillance infrastructure after the crisis has passed. While the need for digital contact tracking is clear, Canadians must take steps to protect their personal data.

Non-technical recommendations

It will be important for Canadians to discuss these systems before the plans are implemented and laws that may violate the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms are passed, particularly with regard to the safety of the person. Hopefully, the conversation Canadians have with their provincial leaders and federal counterparts will include the following:

- A sunset clause to define when surveillance ends.

- A chain of custody agreement for past data between government, industry, and researchers, which includes a process to delete data.

- A plan to protect data sovereignty, which ensures that data is subject to Canadian laws and governance structures.

- A public use of judicial oversight by government, industry, and investigators to ensure that the laws we choose as Canadians are followed.

- A commitment to corporate responsibility if our data is misused, stolen or sold.

Tracking digital contacts is likely to become central to the government’s approach to stifle the resurgence of the virus and reopen the economy.

The complexity of these systems is a risk for the general public that may agree with something that is not well understood. It is essential to inform the public about these risks before governments take extraordinary powers and infringe on our civil liberties.