[ad_1]

Editor’s Note: Find the Latest COVID-19 News and Guidance on Medscape Coronavirus Resource Center.

“This is how black people die.”

These are some of the last words from Susan Moore, MD, a family physician in Carmel, Indiana, who was diagnosed with COVID-19 on November 29. But even her training as a medical doctor couldn’t help it from what she believes was the systemic racism she endured while fighting for her life at the Indiana University Health Hospital in Indianapolis. She died last sunday

at 52 years old.

A Jamaican immigrant who came to the United States in the early 1970s with her family, Moore was an industrial engineer at 3M for nearly a decade before entering the University of Michigan School of Medicine, where her family says she was a student. honorary. A classmate from medical school remembered her as “kind, hard-working, bright and generous.”

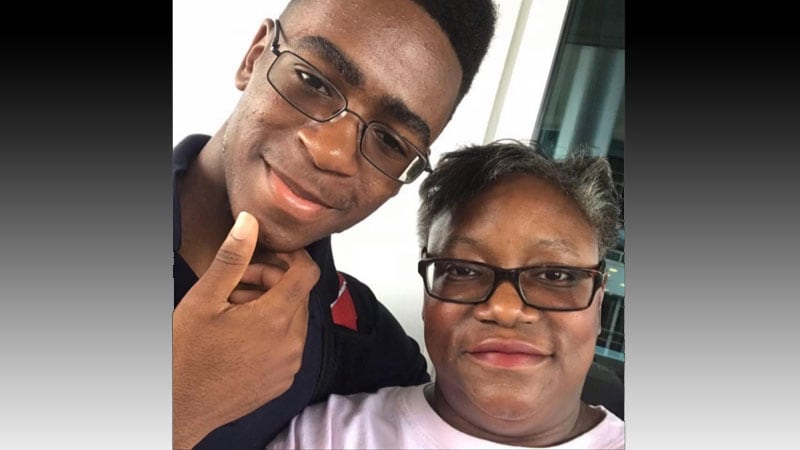

Dr. Susan Moore and her son, Henry

Moore, a single mother, was the sole breadwinner for her two parents who suffered from dementia and lived with her and their 19-year-old son, Henry Muhammed, a freshman engineering student at Indiana University. Friends, like Kimberly Knox, who have known Moore since her college days, said she was a phenomenal doctor who loved to practice medicine and help people. “He was a very studious and caring person,” Knox said. “He just got excited when he talked about medicine, his son and his parents. And he always stood up for his patients and made sure they received proper care.”

Moore said her treatment at the hospital had gotten so bad that in early December she posted a video on Facebook, begging her fellow doctors to help save her. Sitting on a hospital bed with a nasal cannula in her nose, she cataloged a long litany of complaints about the poor care she received. And since she was a doctor, I knew best.

He had to beg for remdesivir, the antiviral drug used to fight COVID-19, because his doctor initially claimed he did not qualify for more than two doses of the drug. “She knew two doses were insufficient for her treatment,” said Linda Burke, MD, an obstetrician / gynecologist in Orlando, Florida, who is in a private Facebook group with some of Moore’s colleagues. “The fact that she had to defend him is embarrassing.”

In the video, Moore said her doctor also refused to give her narcotic pain relievers, despite her excruciating pain; He noted, “all I could do is cry.” When a subsequent CT scan revealed that she had fluid and new blood clots in her lungs, and swollen lymph nodes in her neck, it finally subsided, but it took another 5 hours before she was relieved. “It made me feel like I was a drug addict and knew that I was a doctor. Why do I have to prove something is wrong with me in order for my pain to be treated?” he asked plaintively on the video. “If I were white, I wouldn’t have to go through that.”

The evidence suggests that Moore’s anger was justified. Studies, including one conducted by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco in 2016, have consistently shown that black patients are half as likely as their white counterparts to receive prescriptions for narcotic pain relievers.

Moore was concerned that posting the video would backfire, but was pleasantly surprised by the hospital’s response, according to Knox. From her hospital bed, Moore was able to advocate for herself and moved up the chain of command to file a complaint with the medical director of the IU Health System. He assured her that her concerns would be addressed, that there would be diversity training, and that hospital administrators were working to obtain an apology from the doctor who she believes treated her so poorly.

Moore’s care did improve and she was subsequently released from the hospital. “She just didn’t want to be in that hospital,” Knox said. But less than 12 hours later, her condition rapidly deteriorated: her temperature rose to 103 ° F (39.4 ° C), her blood pressure dropped to 80/60, and her heart was beating at 132 beats per minute. “These people were trying to kill me,” Moore later noted in a Facebook post about IU Health staff. “Clearly, everyone agreed that I was fired too soon.”

He checked into another nearby hospital, St. Vincent Health Center (where, as Medscape Medical News previously reported, black pediatrician Chaniece Wallace died in childbirth in October). Moore had developed bacterial pneumonia, as well as COVID-19 pneumonia, and her latest Facebook post indicated that she was being transferred to the ICU, where she remained on a ventilator for 10 days. Early in the morning of December 20, he died. Her son, Henry, who was allowed into ICU, was by her bedside.

A representative from IU Health said she was saddened to learn of Moore’s death, but could not comment on a specific patient. “As an organization committed to equity and the reduction of racial disparities in health care, we take allegations of discrimination very seriously and investigate all allegations,” a hospital spokesman said in a statement. Still, “we stand behind the commitment and expertise of our caregivers and the quality of care that is provided to our patients every day.”

Would Susan Moore still live if she had had a different care? It is a difficult question to answer. But African Americans are infected with COVID-19 at a rate nearly three times higher than white Americans and twice as likely to die from the virus, according to an August 2020 report by the National Urban League, which is based on Johns Hopkins data. College.

“The delays in her treatment and her inappropriate discharge because she was so frustrated,” Burke said, “could have made a significant difference in her outcome.”

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

[ad_2]