[ad_1]

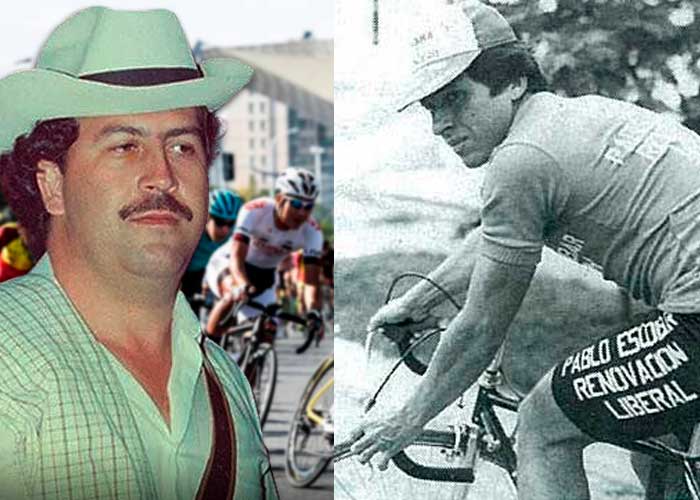

When he was eight years old, Pablo Escobar, riding on the handlebars of his brother Roberto’s bicycle, was climbing the Minas peak in Caldas. There he saw how the first idol he had in his childhood, Ramón Hoyos from Antioquia, destroyed Italian Fausto Coppi, the best cyclist of all time, in a regional tournament. Among the clouds curled on the top of the mountain, Pablo Escobar fell in love with this sport.

Years later, when his family moved to Medellín, the bicycle became part of the family economy. Pablo, Roberto and Gustavo Gaviria, the three cousins, used it to make market homes along the steep streets that surrounded the traditional houses of the El Poblado neighborhood. They played the Tour of Colombia among themselves and dreamed, like the whole country, of seeing a national team compete in the Tour de France. Roberto believed that if he devoted himself to the discipline, he could become a great cyclist. And he almost made it.

While Pablo took the path of crime and illegality, Roberto, in 1965, won the Gold medal of the Bolivarian Road Cycling Games held in Guayaquil and the Vuelta a Oriente. A year later, he was ninth in the Vuelta al Táchira and represented Colombia in the Pan American Cycling Championships in Chile, in addition to reaching the bronze medal in the national championships. He managed to win 37 stages in five years of pedaling. In addition to the medals, which crowned him the third rider in Antioquia after Cochise Rodríguez and Ñato Suárez, cycling left him the nickname by which he would be known for the rest of his life: the Bear. Sports narrators christened him in the early 1970s, after seeing him hit a muddy goal like a muddy bear.

But cycling physically defeated him and he preferred, at the beginning of the 70s, a job in the repair shop of a well-known electrical appliance company: Mora Hermanos. He remained linked to the sport as a coach of Antioquia teams that came to compete in Panama, Ecuador and Venezuela.

Manizales was his destination in 1975, where he set up a factory to create bicycle frames that bore its own name: El Ositto. Then he appeared again in his life and forever his younger brother: Pablo.

He found in the factory the opportunity to justify the tons of money that came to him from the marimbera bonanza, the smuggling and the theft of tombstones that he resold in the towns of Antioquia. With his fixed idea, Roberto thought of building and sponsoring a team capable of competing in Europe. Then the Ositto team was born.

Without abandoning the idea, his brother Pablo moved on the other side and in 1977 he began to sponsor the Clásico de Antioquia, whose trophy he handed out with his own hands. Their project was to have El Ositto in the Tour de France. They hired a coach who was up to the task, Rubén Darío Gómez, and riders of the stature of Manuel Ignacio Gutierrez, winner of the Vuelta a la Juventud in 1975.

Roberto also wanted to be the president of the National Cycling Federation and started with the Caldas League, an aspiration that confronted him since then, Miguel Ángel Bermúdez, boss of Colombian cycling. The absence of the Bear, who equipped with a Kodak 110 camera, traveled to the world championships in Bonn in 1978, was the opportunity that Bermúdez took to remove him from office. Anger festered her for four years.

In 1982, the Medellín Cartel blew up a bomb in the federation president’s car; Bermúdez was saved by a hair. Although the key was only the Escobars, after the attack they disappeared forever from the cycling scene.

Gone was the dream of having a team that would compete in the Tour de France. They had to console themselves in continuing incognito, on the edge of the road, hidden in their “goat” – a modified jeep with large armchairs, a bar, air conditioning and provided, of course, with dozens of perfectly armed bars – the arrivals at the most wild of the Tour of Colombia.

The frustration he tried to mitigate with what he could do with his own fortune: he built a private velodrome a few blocks from the El Tesoro shopping center in Medellín. The pleasure of watching pedaling was satisfied by Alfonso Flórez Ortiz, the Santander rider, who won the 1980 Tour de la Juventud in France, with track teams armed just for the Escobar brothers to recreate. But the war was in charge of extinguishing his cycling fever forever.

[ad_2]