[ad_1]

His life was a constant of victories and defeats, of deaths and resurrections in which a soccer ball was always by his side. For this reason, on the day of his farewell from the courts he said: “The ball is not stained.”

It will be necessary to remember him in the center of the field of the La Boca stadium on November 10, 2001, with a loose tear, the day of his official farewell to football, repeating over and over again that “the ball is not stained”, admitting that If someone was hurt by his drug addiction, it was him, and between pause and pause, looking into the distance, at the crowded stands of people who, too, shouted and sang “Maradoooooooo, Maradoooooooooo”. We will have to remember him a few years before, shortly before the 1986 World Cup began in Mexico, when he began to speak with the players from Italy and Brazil, and with some of his teammates in Argentina, to make them rebel against the FIFA and they will change the schedules of the matches, because at 12 o’clock, or at one, with that sun and the pollution and the altitude, they were going to die.

In 86 Maradona was renamed D10S. “Never was a player as influential in a single World Cup as Maradona in that Cup,” one of his rivals in the final, Lottar Mathaus, would say over time. From the first game to the last, against Germany, Diego Maradona made the impossible possible, until he forced Joao Havelange, FIFA president, to shake his hand and deliver the World Cup to him in the main box of the Azteca stadium, swallowing his words and his insults, because days before, before the Argentine 10 attempted rebellion, he had called him “damn little black head.” That day, on the afternoon of June 29, Havelange vowed revenge and took the word revenge personally. And he took revenge on that “little black head” that his whole life was proud of being a “little black head”, cutting off his legs once and twice years later.

“They cut off my legs,” Maradona said eight years later in the middle of a chaotic press conference in Boston, United States, a few minutes after Julio Grondona, the president of the Argentine Football Association (AFA), notified him that by doping he had been out of the World Cup. Maradona had returned to football and the Argentina team after Colombia’s 5-0 win at the River Plate stadium. He lost 15, 20 kilos. He trained day and night, and returned to save his team in a play-off against Australia and, later, in the 1994 World Cup. But one day he ran out of the pills he had been prescribed, and his physical trainer bought him more , with the same compound, but with an extra component: ephedrine, and ephedrine was one of the thousand prohibited substances.

They cut off his legs, as they had cut them three years before, when he was suspended in the Italian League for 18 months, because an examination in a laboratory that only existed to detect his addiction to cocaine determined that he had played a game with his team, Naples, under the influence of drugs. Maradona said that coke had nothing to do with playing soccer, but it didn’t matter. Someone, or many, and from above, had long since lowered the hammer to convict him of whatever it was. He was guilty of the drug. He was guilty of having beaten Silvio Berlusconi’s Milan a match that “he should not win”, as he later said. He was guilty of having been the captain of Argentina that eliminated Italy in the 1990 World Cup in Naples and left it out of its World Cup. He was to blame for reminding southern Italians that the north had always humiliated them.

He was the culprit of everything for having faced power and the powerful. The media that praised him before, because to say Maradona was to say money, a lot of money, and to say Maradona was to sell copies of newspapers and magazines and raise the rating of whatever program named him, they began to crucify him. On April 26, 1991, for example, the Buenos Aires police raided an apartment he was in, in the Caballito neighborhood, and arrested him, drugged. When Maradona left the building, his gaze cloudy, lost, glassy, there were more than a hundred photographers from the different media in the country on the street. “Someone warned them,” he later commented. Likewise, his photo as a “criminal” had already been around the world, and in one and another and another place people repeated that he was a “drug addict”, an adjective that they hung on him forever until the end of his days.

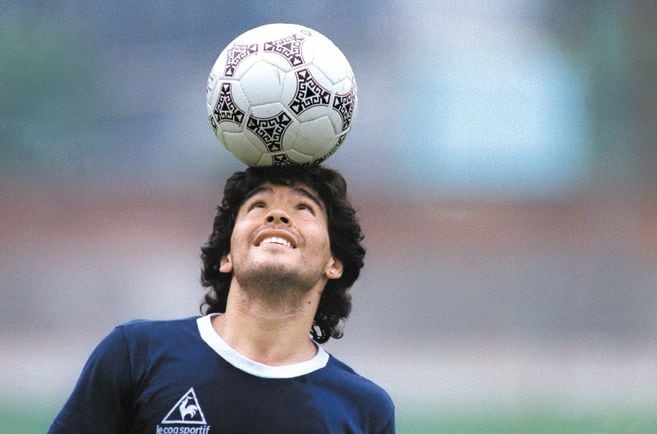

Maradona was the enemy to be defeated, the one they had to humiliate. His only weapon was soccer. The ball. With her, for her, he had hypnotized the fans of Argentinos Juniors since he was a “little onion”, before his debut in the first division, on October 20, 1976 against Talleres de Córdoba. Years after, many years, some collector of anecdotes and almost invisible stories recalled that when he went to look for the first photo of Maradona’s first play in the first division, he found nothing. However, he continued in his search. He went through files and archives, investigated, thought, put the dots together, until he found the image he so badly needed. A photography assistant had kept it in any envelope, with a general inscription that read: “Photos Argentinos Juniors-Talleres- October 20, 1976.”

With the same ball from then, even if it changed color and brand, that worn and deflated ball that an uncle had given him and with which he slept when he was barely two years old, Maradona later dazzled Boca fans in 81st he hypnotized the world, as before and as always, making the impossible possible. And then, by gusts, despite a fracture of the tibia and fibula and hepatitis, he fascinated those of Barcelona, and finally the Neapolitans, who hung flags with his face and his name next to the venerated saint of the city, San Jenaro. Maradona restored Naples and the Neapolitans to their former importance. He put them back on a map not only of football, but of history, and he did it with a ball.

And with a ball he was world champion, and he forced Havelange to shake his hand, and took revenge, his revenge, of the English for those killed in the Falklands War with two anthological goals that captured his side of a humble neighborhood and of Soccer D10S. With a ball he laughed, celebrated, sang and cried, and said, as in a kind of prayer, “the ball does not stain.”

[ad_2]