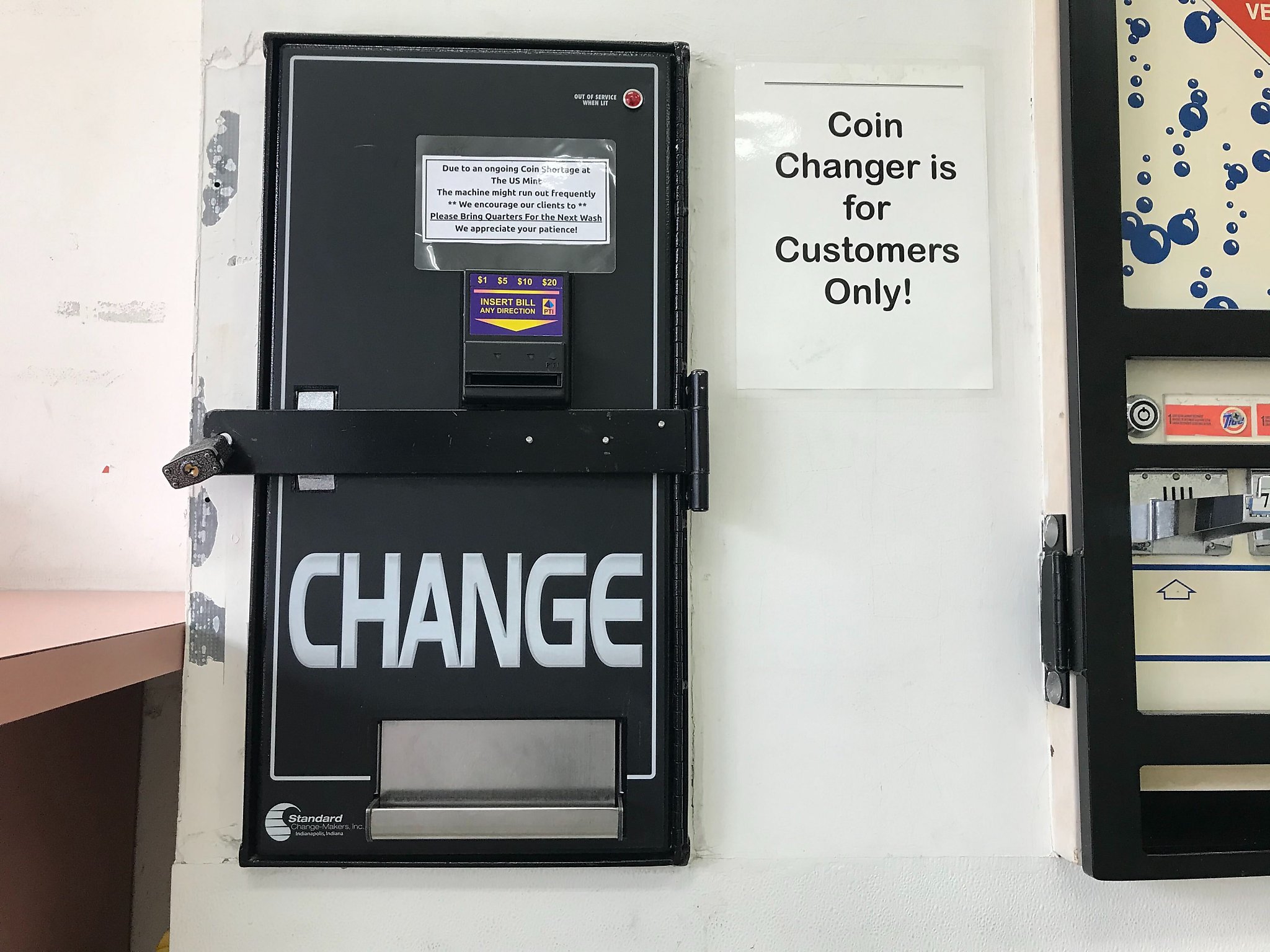

In recent weeks, Oakland A1 laundry owner Nesanet Tamirue has had to be extremely careful with coins. She put up a sign asking customers not to go to bed unless they are for the laundry machines.

It has not always worked. Sometimes people who enter don’t care, or feel like they have no choice, clandestinely withdrawing more than $ 10 in coins before rushing in. At any other time, it might have been fine. Now it is not.

This is because during the coronavirus pandemic, the flow of coins in the Bay Area has stalled, say banks and business owners, reflecting a national shortage that is significantly affecting several companies, including laundries, convenience stores and banks.

In recent months, as the regular flow of consumers has chosen to stay home or avoid physical cash altogether, the typical flow and circulation of money has become dysfunctional.

US Mint accelerates as banks ration

The U.S. Mint, the maker of the nation’s coins, has had to speed up its coin production to introduce new batches into the system. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve, which distributes coins across the country, has been strategically allocating its coin reserve to deal with stunted circulation.

The result has been that banks are receiving less and are forced to ration what little they have. That has left a large swath of business owners, who depend on currencies to carry out daily transactions on their boxes, without knowing how they can continue their operations.

The impact on many essential businesses in the Bay Area has been significant.

Ibrahim Bharachua, owner of Cow Hollow Laundromat and Dry Cleaners, said he had to turn an employee into a live currency changer to prevent customers from taking too much out of machines and avoiding running out of rooms.

The last time he went to the bank, he said, they told him they could only give one roll, two, if he owned a business. The teller told him that the bank received only $ 500 in quarters per week, when it generally orders $ 2,000.

‘It is a serious situation’

“Some people want more rooms and I say ‘sorry’,” said Bharachua, who has owned his laundry since 1991. “It is a serious situation for a laundry, because you cannot do business without coins.”

Despite the fact that many small businesses have switched to mobile payment options, laundries are still largely a coin-operated industry. In fact, 89% of the nation’s laundries still accept coins as payment, while 60% depend solely on coins to operate, said Brian Wallace, president and CEO of the Coin Laundry Association, a membership system of more than 2,000 laundry owners, commercial equipment distributors. and other professions in the industry.

To cope with the maddening shortage, some of the association’s members have tried various solutions: store signs that encourage customers to bring change from home, initiatives to get local people to bring their dusty piggy banks for money in cash and even B2B. – Exchanges of money at the level between, for example, a lucky laundry owner in Cleveland who has more rooms than he needs, and one in Columbus who has not been so lucky. The association facilitates such transactions through an online forum.

“We are doing our best with this, but at the end of the day, if we can’t make changes, we can’t make money,” Wallace said.

At the branch level, banks have to find strategic ways to ration the few currencies they now have through the system.

“We have a lot of dissatisfied customers,” said Héctor Guerrero, manager of Wells Fargo at 6100 Geary Street. “But the majority of commercial customers are the most affected.”

Right now, Guerrero says the bank has about $ 100 in quarters for the entire branch. The branch generally has more than $ 500 in quarters a week to distribute to its customers. Since the shortage, he has seen the reserve drop to $ 30.

Day-to-day coping strategy

He does not know what to do. But each day requires some strategy.

“I give $ 20 to each of my ATMs, and they distribute it the way they can,” he said.

A few minutes before picking up the phone to discuss the coin shortage, Adnan Alameri, a 7/11 manager on Sutter Street, said that a customer had left because Alameri was unable to provide the exact change. He said to the customer that he could buy something else and even tried to give him a discount, but he lost the sale.

It is a scene that has happened more than once since the shortage of coins came to your store. They gave him $ 10, a roll, in quarters the last time he visited the bank.

It usually goes through eight a day.

On June 23, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin noted that the United States was “a little behind on coins,” but that he believed the shortage would be resolved, according to the New York Times. The Federal Reserve’s rationing plan, which began on June 15, was to be a “temporary measure.”

Requests for comment to the US Mint were not immediately answered. In a statement emailed to The Times, spokesman Michael White said coin shipments are on the rise, and that the Mint will send 1.35 billion coins each month for the rest of 2020, compared to a average of 1 billion per month.

Located on top of a hill on Buchanan Street and Duboce Avenue, San Francisco Mint is one of six US Mint facilities across the country. She used to make circulation coins, but currently only produces commemorative coins and medals. The location made coins until 1974. San Francisco’s regular circulation coins are now made in the Denver and Philadelphia mints.

The historic United States Mint building on Fifth and Mission streets in San Francisco has been retired as a money-making plant for more than 80 years.

Annie Vainshtein is a reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle. Email: [email protected] Twitter: @annievain