Of Popular Mechanics

Scientists don’t know much about the ice giants at the other end of our solar system. They are a constant source of mystery and intrigue.

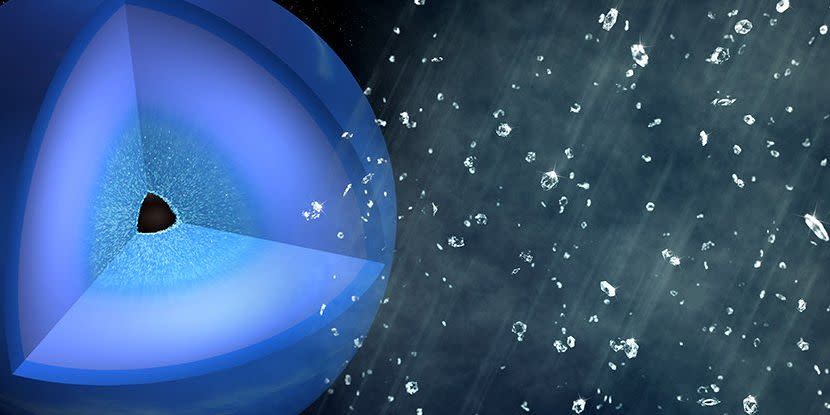

Take the riddle, for example, of how chemical reactions within Neptune and Uranus can make diamonds rain down on the nuclei of planets. Under immense pressure below the surfaces of the planets, the carbon and hydrogen atoms come together, forming the crystals.

Scientists first conducted an experiment to explore this phenomenon in 2017, but now they have finally narrowed down exactly how these diamonds were formed, publishing their results today in the journal. northSecure communication.

“Our experiments are delivering important model parameters where, previously, we only had massive uncertainty,” said physicist Dominic Kraus of the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf research institute in Germany, in a press release. “This will become increasingly relevant as we discover more exoplanets.” Kraus and his team conducted the experiments at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory at Stanford University.

To better understand how this molecular magic occurs, the researchers recreated the diamond shower within Neptune’s nucleus in the laboratory. Instead of using methane, which would be found within the ice giants, as a sample, scientists used hydrocarbon polystyrene (C8H8), colloquially known as Styrofoam.

Kraus and his colleagues applied heat and pressure to the polystyrene and then used an optical laser to generate shock waves that rippled through the material. When those shock waves were found, temperatures rose to 8,540 degrees Fahrenheit. (The Earth’s core, for reference, is about 10,800 degrees Fahrenheit.) The pressure inside the material also shot up.

“We produce around 1.5 million bars, which is equivalent to the pressure exerted by the weight of about 250 African elephants on the surface of a miniature,” said Kraus.

The scientists then used SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) instrument to direct the x-rays into the sample and measure how light bounced off the electrons inside it. For the first time, they watched the chemical reaction unfold within the non-crystalline substance. The hydrocarbons separated; Carbon quickly turned into diamond and sank as hydrogen escaped.

Kraus says the experiment may explain why the Neptune nucleus produces a bewildering amount of energy, more than double the amount it absorbs from the sun. The researchers suspect that these diamond blades could generate gravitational energy and subsequently thermal energy as they rain down on the planets.

Ultimately, the experiment will help scientists solve mysteries here in our own solar system and in distant star systems.

You might also like