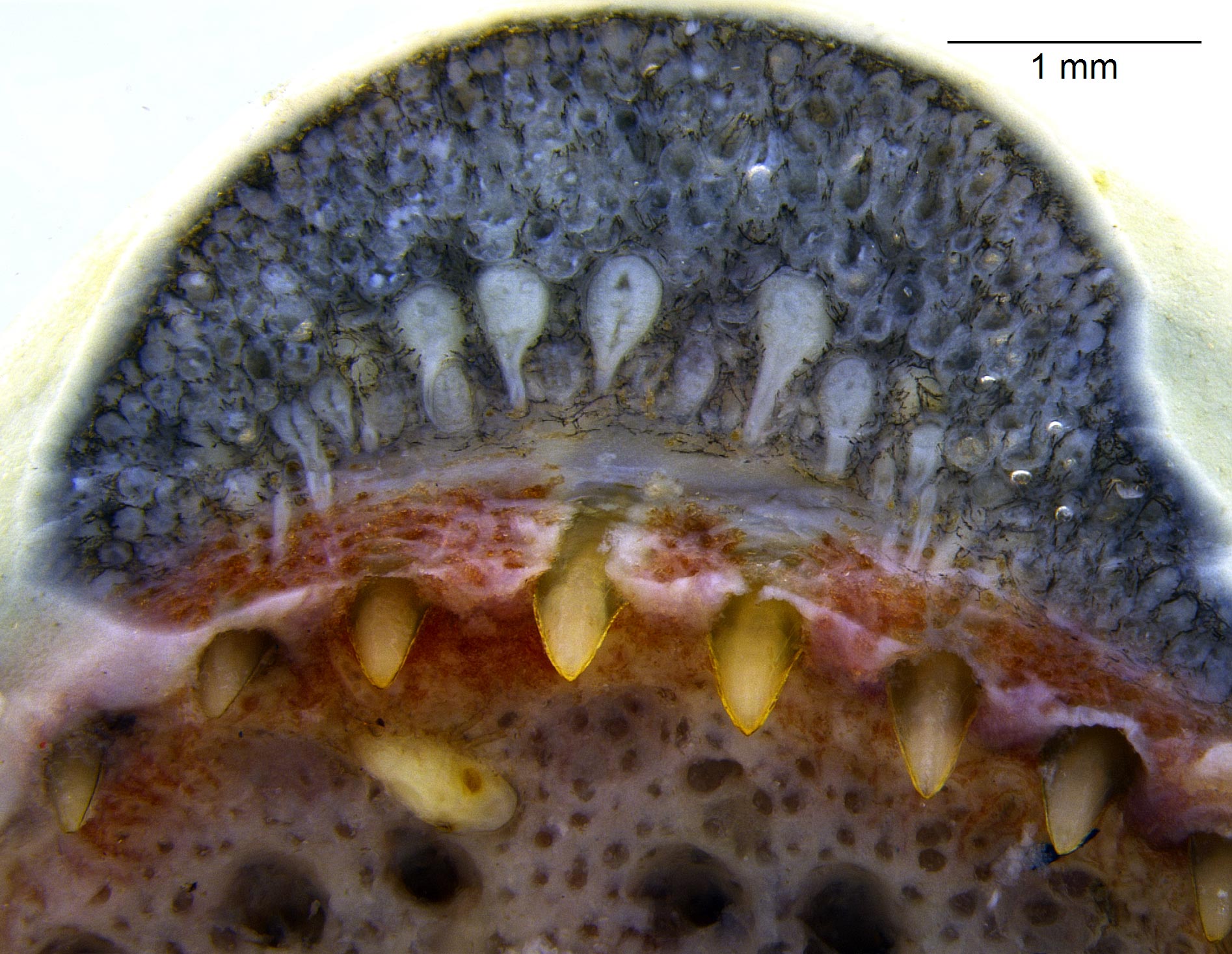

An enlarged image of the mouth of a ringed cecilium, Siphonops annulatus, reveals snake-shaped dental glands. Researchers from the Butantan Institute in Brazil and Utah State University say the glands may indicate an early evolutionary design of the organs of oral venom. Credit: Butantan Institute, Brazil.

Scientists from Utah State University and the Butantan Institute publish evolutionary findings in iScience.

Biologist Edmund ‘Butch’ Brodie, Jr. of Utah State University and colleagues at the Butantan Institute in São Paulo report the first known evidence of oral venom glands in amphibians. His research, supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development of Brazil, appears in the July 3, 2020 issue of iScience.

“We think of amphibians (frogs, toads, and the like) as basically harmless,” says Brodie, professor emeritus of the USU Department of Biology. “We know that several amphibians store unpleasant and poisonous secretions in their skin to deter predators. But knowing that at least one can inflict mouth injuries is extraordinary. “

A ringed cilium, Siphonops annulatus. Neither snakes nor worms, the cilia are snake-shaped amphibians related to frogs and salamanders. Researchers from Brazil’s Butantan Institute and Utah State University report that the creatures have poisonous dental glands, the first known discovery of snake-like glands in amphibians. Credit: Carlos Jared, Instituto Butantan.

Brodie and his colleagues discovered the oral glands in a family of cilia, snake-like creatures related to frogs and salamanders. Neither snakes nor worms, the cilia are found in the tropical climates of Africa, Asia and America. Some are aquatic, and others, such as the Ringed Cecilium (Siphonops annulatus) studied by Brodie’s team, live in burrows they create.

In 2018, the team reported that the species secreted substances from the skin glands at both ends of its snake-shaped body. Focused on the head and extending the length of the body, the creature emits a mucous lubricant that allows it to quickly dive underground to escape predators. At the tail, the ciliates have glands armed with a toxin, which acts as a last line of chemical defense, blocking a tunnel in a hurry for hungry hunters.

“What we did not know is that these cecilies have small fluid-filled glands in the upper and lower jaws, with long canals that open at the base of each of their spoon-shaped teeth,” says Brodie.

Researcher Pedro Luiz Mailho-Fontana, from the Butantan Institute of Brazil, left, and biologist Edmund “Butch” Brodie, Jr. from Utah State University, USA, on the Logan, Utah, campus of the USU. Credit: M. Muffoletto

Her research colleague Pedro Luiz Mailho-Fontana, who studied with Brodie as a visiting graduate student at the Logan campus of USU in 2015, noticed the oral glands never described before. Through embryonic analysis, Mailho-Fontana, the first author of the article, discovered that the glands, called “dental glands,” originated from tissue other than that of slime and the poisonous glands found in the skin of the Cecilias.

“The poisonous skin glands form from the epidermis, but these oral glands develop from the dental tissue, and this is the same source of development that we find in the poisonous glands of reptiles,” he says.

The researchers suppose that the cilia, equipped without limbs and only with a mouth to hunt, activate their oral glands when they bite their prey, including worms, termites, frogs and lizards.

The team does not yet know the biochemical composition of the liquid retained in the oral glands.

“If we can verify that the secretions are toxic, these glands could indicate an early evolutionary design of the organs of the oral venom,” says Brodie. “They may have evolved in the cilia before the snakes.”

For more information on this discovery, read Snake-like venom glands discovered along the teeth of amphibians.

Reference: “Morphological evidence for an oral venom system in Cecilia’s amphibians” by Pedro Luiz Mailho-Fontana, Marta Maria Antoniazzi, Cesar Alexandre, Daniel Carvalho Pimenta, Juliana Mozer Sciani, Edmund D. Brodie Jr. and Carlos Jared, 3 of July 2020, iScience.

DOI: 10.1016 / j.isci.2020.101234