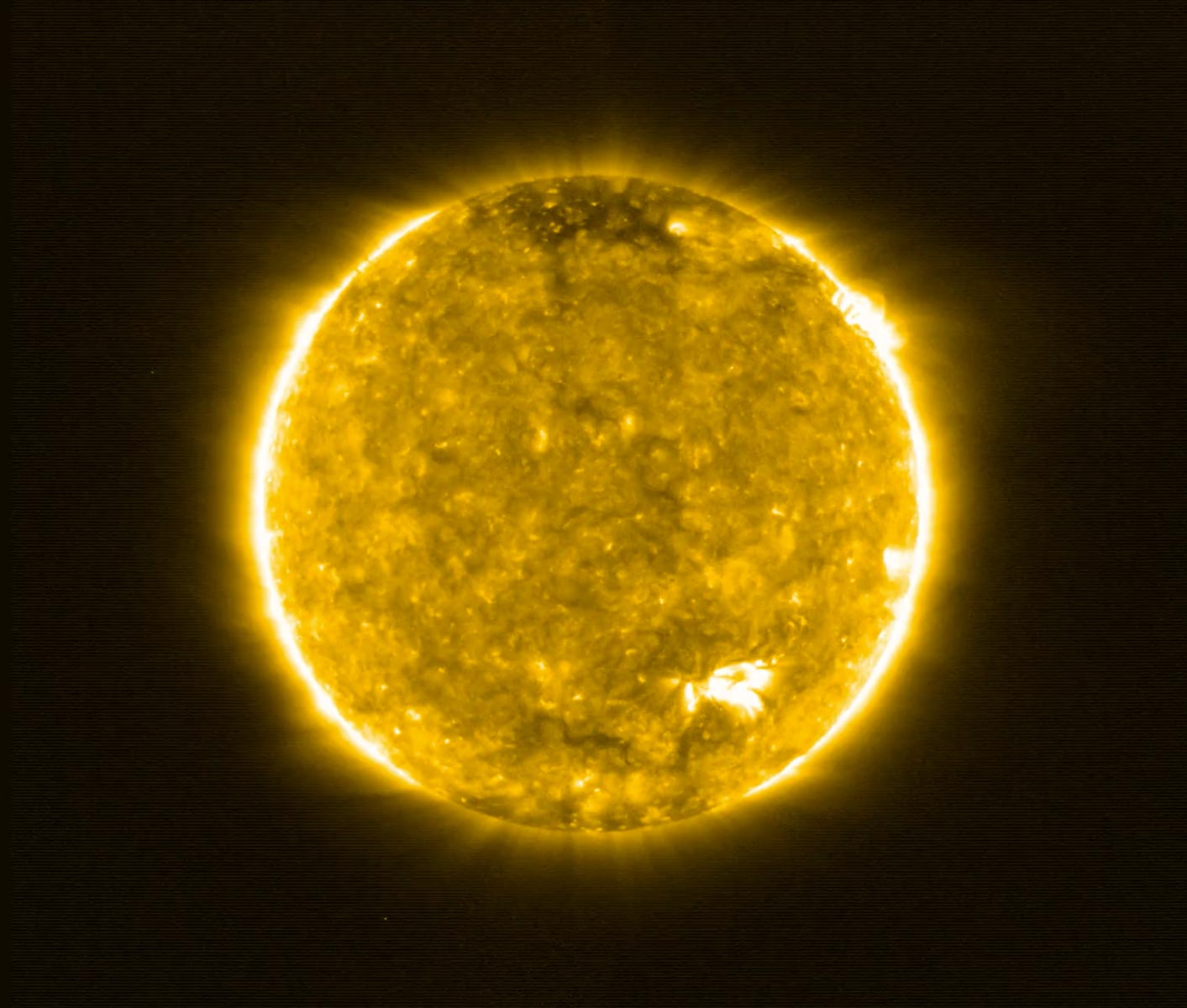

The Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) on ESA’s Solar Orbiter spacecraft took this image on May 30, 2020. It shows the appearance of the Sun at a wavelength of 17 nanometers, which is in the extreme ultraviolet region of the spectrum. electromagnetic. Images at this wavelength reveal the Sun’s upper atmosphere, the corona, with a temperature of around 1 million degrees. EUI takes full disk images (top left) using the Full Sun Imager (FSI) telescope, as well as high resolution images using the HRIEUROPEAN UNION V telescope. Credit: Solar Orbiter / EUI Team / ESA & NASA; CSL, IAS, MPS, PMOD / WRC, ROB, UCL / MSSL

The first images of Solar Orbiter, a new ESA solar observation mission and POT, have revealed ubiquitous miniature solar flares, called “bonfires,” near the surface of our nearest star.

According to the scientists behind the mission, seeing phenomena that were not observable in detail before hinting at the enormous potential of Solar Orbiter, which has just completed its first phase of technical verification known as commissioning.

“These are just the first images and we can already see new interesting phenomena,” says Daniel Müller, a scientist at ESA’s Solar Orbiter Project. “We really didn’t expect such good results from the beginning. We can also see how our ten scientific instruments complement each other, providing a holistic image of the Sun and the surrounding environment. “

Solar Orbiter, launched on February 10, 2020, carries six remote sensing instruments, or telescopes, that capture images of the Sun and its surroundings, and four on-site instruments that monitor the environment around the spacecraft. By comparing the data from both sets of instruments, scientists will gain insight into the generation of the solar wind, the stream of charged particles from the Sun that influences the entire Solar System.

The unique aspect of the Solar Orbiter mission is that no other spacecraft has been able to take images of the Sun’s surface from a closer distance.

First views of the Sun obtained with the Solar Orbiter EUI on May 30, 2020, revealing the ubiquitous miniature eruptions called ‘bonfires’. Credit: Solar Orbiter / EUI Team / ESA & NASA; CSL, IAS, MPS, PMOD / WRC, ROB, UCL / MSSL

Closer images of the Sun reveal new phenomena.

The fires shown in the first set of images were captured by the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) of the first perihelion of the Solar Orbiter, the point on its closest elliptical orbit to the Sun. At that time, the spacecraft was only 77 million kilometers from the Sun, about half the distance from Earth to the star.

“Campfires are small relatives of the solar flares that we can observe from Earth, millions or billions of times smaller,” says David Berghmans of the Royal Observatory of Belgium (ROB), principal investigator of the EUI instrument, who takes images of high resolution. from the lower layers of the Sun’s atmosphere, known as the solar corona. “The Sun may seem calm at first glance, but when we look closely, we can see those miniature flares everywhere.”

Scientists do not yet know if the bonfires are just small versions of large flares, or if they are powered by different mechanisms. However, there are already theories that these miniature flares could be contributing to one of the most mysterious phenomena in the Sun, coronal heating.

One of the newly discovered ‘bonfires’ in a Solar Orbiter EUI image. The circle in the lower left corner indicates the size of Earth for the scale. Credit: Solar Orbiter / EUI Team / ESA & NASA; CSL, IAS, MPS, PMOD / WRC, ROB, UCL / MSSL

Unveiling the mysteries of the sun

“These bonfires are totally insignificant by themselves, but summing up their effect on the entire Sun, they could be the dominant contribution to warming the solar corona,” says Frédéric Auchère, from the Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale (IAS), France, EUI principal investigator.

The solar corona is the outermost layer of the Sun’s atmosphere that stretches millions of kilometers into outer space. Its temperature is over a million degrees. Celsius, which is an order of magnitude warmer than the Sun’s surface, at 5500 ° C ‘cool’. After many decades of studies, the physical mechanisms that heat the corona are still not fully understood, but identifying them is considered the ‘holy grail’ of solar physics.

“Obviously it is too early to know, but we hope that by connecting these observations with measurements from our other instruments that ‘feel’ the solar wind as the spacecraft passes, we will eventually be able to answer some of these mysteries,” says Yannis Zouganelis, Associate Scientist at the Solar Orbiter Project at ESA.

Complementary views of the Sun and its outer atmosphere, or corona, based on the EUI, PHI, Metis and SoloHI instruments at Solar Orbiter.

Seeing the other side of the sun

The Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) is another cutting-edge instrument on board the Solar Orbiter. Make high-resolution measurements of the magnetic field lines on the sun’s surface. It is designed to monitor active regions on the Sun, areas with especially strong magnetic fields, which can lead to solar flares.

During solar flares, the Sun releases bursts of energetic particles that enhance the solar wind that constantly emanates from the star into the surrounding space. When these particles interact with Earth’s magnetosphere, they can cause magnetic storms that can disrupt telecommunications networks and power grids on the ground.

The Sun and its magnetic properties observed by the Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) instrument at Solar Orbiter. Credit: Solar Orbiter / PHI Team / ESA and NASA

“Right now, we are in the 11-year part of the solar cycle when the Sun is very calm,” says Sami Solanki, director of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Göttingen, Germany, and Principal Investigator for PHI. “But because the Solar Orbiter is at a different angle to the Sun than Earth, we could actually see an active region that was not observable from Earth. That is the first one. We have never been able to measure the magnetic field at the back of the Sun. “

The magnetograms, which show how the strength of the solar magnetic field varies across the surface of the Sun, could be compared to measurements from instruments in situ.

“The PHI instrument is measuring the magnetic field on the surface, we see structures in the corona of the Sun with EUI, but we also try to infer the lines of the magnetic field that go out to the interplanetary medium, where the Solar Orbiter is,” says José Carlos del Toro Iniesta, Co-Principal Investigator PHI, of the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia, Spain.

Combining remote sensing observations from SPICE with on-site SWA measurements. Credit: Solar Orbiter / SPICE Team; SWA team; EUI / ESA and NASA team

Catching the solar wind

The four in the place The instruments in Solar Orbiter then characterize the magnetic field lines and the solar wind as the spacecraft passes.

Christopher Owen of the Mullard Laboratory for Space Sciences at University College London and principal investigator of the in the place Solar Wind Analyzer, adds: “Using this information, we can estimate where that particular part of the solar wind was emitted from the Sun, and then use the mission’s complete set of instruments to reveal and understand the physical processes operating in the different regions in the Sun that lead to the formation of solar wind. “

“We are all very excited about these first images, but this is just the beginning,” adds Daniel. “Solar Orbiter has started a great tour of the inner Solar System, and will get much closer to the Sun in less than two years. Ultimately, it will approach 42 million km, which is almost a quarter of the distance from the Sun to Earth. “

A ‘family portrait’ of the first images and data of the ten instruments of the Solar Orbiter. Credit:

Solar Orbiter / ESA and NASA

“The first data already demonstrates the power behind a successful collaboration between space agencies and the usefulness of a diverse set of images to unravel some of the mysteries of the Sun,” says Holly Gilbert, director of the Division of Heliophysics Science at the Center of Goddard Space Flight from NASA. and Scientist at the Solar Orbiter Project at NASA.

Solar Orbiter is an international collaborative space mission between ESA and NASA. Nineteen ESA Member States (Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom), such as as well as NASA, contributed to the science and / or spacecraft payload. The satellite was built by prime contractor Airbus Defense and Space in the United Kingdom.

The Solar Orbiter First Images photo gallery is available here.

For more information on these early data from the Solar Orbiter, see “Bonfires” detected in the sun in the first images of the Solar Orbiter.