When Steve Cunnell won the city council seat in this city of 8,000 last year, he thought he would deal with pit and affordable housing.

Instead, he finds himself at the center of a heated debate over how to fight the coronavirus, which has never happened before in Montana.

The governor of the state, Steve Block, a Democrat who is in the final stages of tight membership in the U.S. Senate, was reluctant to impose sanctions that would harm his campaign. Command.

There was little appetite for it in Rousseau’s Flathead County, where the health board has been dominated by a clear doctor, arguing that the epidemic is a hoax.

Who left Whitefish City Council.

“We’re the last line of defense,” Quinnell, a 49-year-old social studies teacher at the high school, told members of his fellow councilors during a public online meeting this week. “Will we lead? Or will we just follow the unbelievers of the county? ”

Places like Whitefish can afford to see an epidemic as a distant big city problem once in a while. By mid-September, the sparsely populated Montana had grown to 140.

But the figure has doubled in the last five weeks as a new wave of infections has re-emerged in the country. More than 85,000 cases were reported nationwide on Friday, the highest in a single day since the outbreak.

The worst epidemics are in the rural Midwest and the Rocky Mountains. Last week, with 6,933 new cases, Montana had the third highest infection rate in the country, second only to Dakota.

The increase in Montana has stripped efforts to conduct contact tracing and stressful health systems across the state.

And as the events of Whitefish show, efforts to curb the deadly surge are pushing against a culture that prides itself on rigid independence and freedom from government regulations.

Early in the epidemic, whitefish, the gateway to ski areas and glacier national parks, moved more decisively than many other communities to contain the virus.

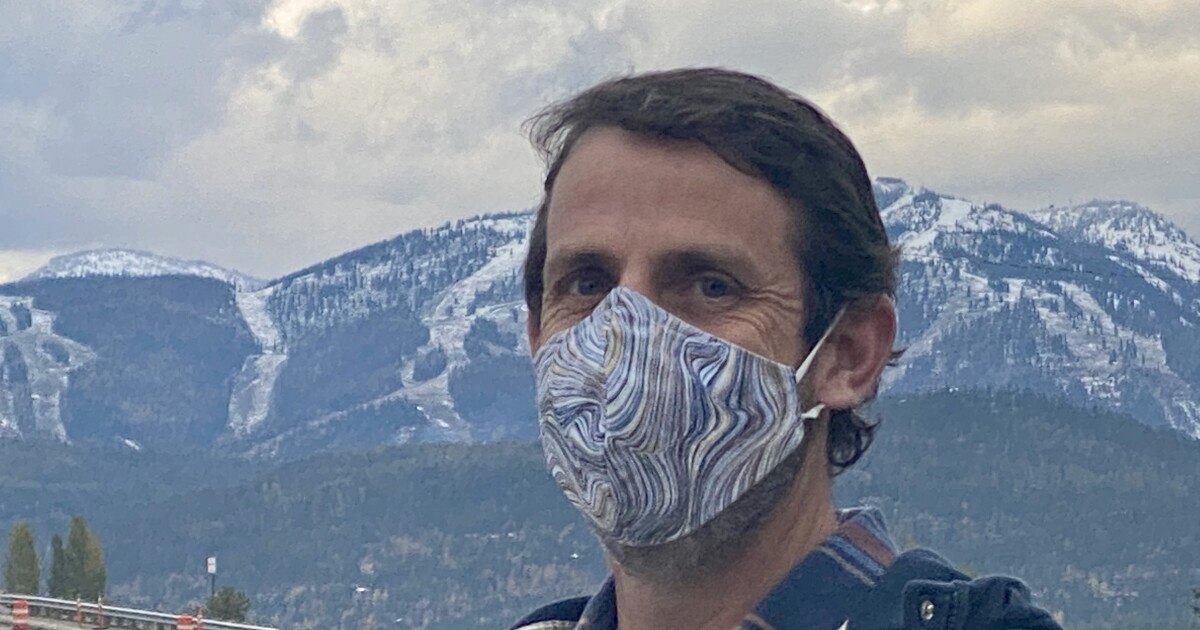

Whitefish Mountain Resort Whitefish, Mont., Has looms at the entrance to Glacier National Park.

(Richard Reed / Los Angeles Times)

Last spring, in Tuma, the city council ordered hotels and short-term rental properties to hire only the necessary workers – a requirement that lasted until the end of May.

Whitefish was also one of the first cities in Montana to allow people to wear a mask – although the governor soon issued a statewide order.

Yet, from the beginning, there was local opposition to such restrictions.

Leading the resistance was Dr. Anne Bukasek, a 62-year-old intern known for her far-right views and opposition to vaccinations.

Flathead county commissioners fired two other doctors with more public health experience and appointed him to the county health board last December – commissioners said the changes would increase diversity of opinion.

Last spring, Bukasek became the hero of anti-people activists across the country, after he addressed a local church saying the federal government was exaggerating the number of coronavirus deaths.

“Freedom is abandoned when people are blessed by fearful people,” he told members of the Liberty Fellowship.

She wore a lab coat and stethoscope to her presentation, which has been viewed more than 860,000 times on YouTube.

The congregation is led by Chuck Baldwin, described by the Montana Human Rights Network as “unofficial respect for the military movement.” He has violated state orders by continuing personal services.

D black. The center’s bookcase, in the center, joins protesters in black, Montina Kalispel, protesting the need for masks in schools.

Dr. Buk’s Bukasek opposes restrictions on slow-spreading coronaviruses, saying the death toll has been exaggerated.

Buccaneers and a small group of allies protested outside schools and government buildings a few times each week as they tried to eliminate mask requirements and make other state sanctions equal to martial law.

His message last summer had some plausible so-called causes and deaths, though whitefish and the national park received more tourists than expected.

Eventually it became clear that Flathead County, with a population of 100,000, would not avoid the kind of suffering experienced in many other parts of the country.

The first major outbreak of whitefish struck a nursing home in August, infecting 43 out of 52 patients – and eventually killing 13 of them.

The county’s largest hospital, Kalispell Regional Medical Center, soon began seeing more admissions to its coronavirus ward.

Ric, a 46-year-old critical care nurse who works night shifts in the 46-year-old ward, can cope with the trauma of dying patients. It was part of the job.

Opponents of the basic safety measures were meant to be for the victims of the epidemic.

“I just felt so deep, so deeply sad that when I saw patients suffering and dying, I realized that our community has moved on and doesn’t really care.”

“I realize there is a historic historical tension between public health and personal freedom.” “But a good part of our community is hitting the state’s mask command, and I still can’t get my head around how this has become politicized and divisive.”

The number of patients in the coronavirus ward has risen to about 29 in recent days, but managers are hiring more nurses if things go wrong.

The recent outbreak in Flathead County – where the total number of infected people has more than doubled in the past three weeks to 2,800 – has led to large gatherings at four churches, four weddings, three political events and two trade shows.

This week the county health department advised residents to stay home as much as possible and limit their out-of-family contacts to no more than six people a week, each for 15 minutes or less. Recommendations have been widely ignored.

The interim county health officer, Tamali St. James Robbins, said in an interview that he has the right to make such measures mandatory but further regulations would be useless because officials were already refusing to implement them in place.

The county prosecutor, Travis Ahner, said he focused on the crime and did not see any issue of breaking up industries for mask violations.

Tamley St. James Robinson, the interim public health officer for Flathead County, refused to impose coronavirus sanctions.

(Richard Reed / Los Angeles Times)

For their part, county commissioners issued a statement this month, “Montana’s constitutional right to make choices about personal protections for themselves.”

“Where does he leave me, just leaves me there?” Asked Robbins.

Speaking of the County Health Board, Bukasek won the latest battle over whether or not to limit social gatherings.

“Statistically, for practical purposes, Covid exists 100% in Montana,” he said during the board’s public online public meeting last week.

“No, it’s not!” Local infectious disease specialist Dr. Jeffrey yelled at Tajade, who said things were likely to get worse without immediate action.

A minute later, he stopped telling her again that she was fed up with his presentation that she was logging in.

“I’m not saying it doesn’t matter who died,” she said after leaving.

At the end of the night, the board members were left with only one proposal: no more than 500 people.

They rejected it by a 5-to-3 vote.

Encouraged this criticism from the governor, who said he was disappointed that the board had ignored experts and that “some people are trying to politicize the virus” to protect health and safety.

“The message was loud and clear that if the spread of the virus in the flathead area is not controlled, schools will have to close, parents will be out of work, businesses will be damaged and hospital beds will run out of capacity,” Bullock told reporters.

This week, he announced that state investigators had conducted spot checks on more than a dozen businesses in Flathead County and that authorities would ask a judge to temporarily close five establishments as “criminal violators” changing mask requirements and social distance norms.

The biggest risk may be winter, as the virus spreads very easily when people are indoors.

In Whitefish, temperatures plummeted Friday as the first major snowfall of the season hit.

“It’s time for action and unfortunately it has fallen on us,” Cunell told his colleagues at this week’s City Council meeting.

The city manager wrote a letter to the health board encouraging him to work. One councilor said another letter to businesses would persuade them to co-operate.

Cunell did not see this issue.

“The county won’t do anything, no matter what letters we write,” he said.

They wanted the council to vote to close the bar by 10pm – usually before it gets crowded and furious – and limit restaurants to 25% capacity.

But the only thing decided by the council was to meet again on Monday, when Halloween weekend, when the whitefish traditionally put on the popular downtown bar crawl, would consider imposing a limit.

In an interview, Cunnell said Whitefish must find a balance between the economy that protects citizens and national, state and county leaders.

“There has been a failure of leadership from a very high level,” he said. “Responsibility keeps pushing downhill, and it ends up in our laps.”