[ad_1]

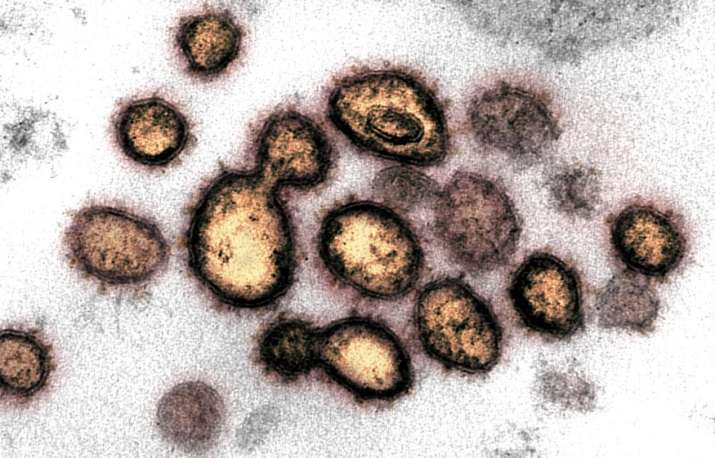

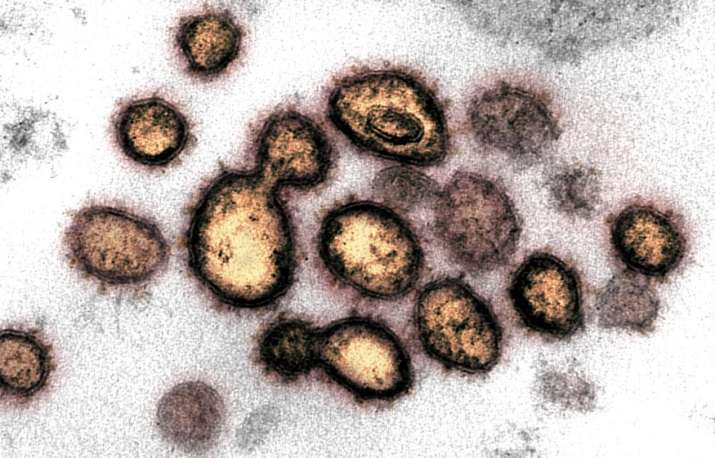

Mutant coronavirus has emerged and is more dangerous, study finds

As the deadly novel coronavirus has wreaked havoc worldwide, scientists have discovered a new strain of COVID-19 that has become worldwide dominant and appears to be more contagious than the one that was initially spread. According to a new study led by scientists from Los Alamos National Laboratory, the strain appeared in Europe in February, migrated rapidly to the east coast of the United States, and has been the dominant strain worldwide since mid-March.

In addition to spreading faster, it can make people vulnerable to a second infection after a first attack with the disease, the report warned.

The 33-page report was published Thursday on BioRxiv, a website researchers use to share their work before it is peer-reviewed, an effort to accelerate collaborations with scientists working on COVID-19 vaccines or treatments. That research has relied heavily on the genetic sequence of previous strains and may not be effective against the new one.

The mutation identified in the new report affects the now infamous spikes on the outside of the coronavirus, which allow it to enter human respiratory cells. The report’s authors said they felt an “urgent need for an early warning” for vaccines and drugs in development worldwide to be effective against the mutated strain.

Wherever the new strain appeared, it quickly infected many more people than previous strains that came out of Wuhan, China, and within a few weeks was the only strain prevailing in some nations, according to the report. The new strain’s dominance over its predecessors shows that it is more infectious, according to the report, although exactly why is not yet known.

The coronavirus, known to scientists as SARS-CoV-2, has infected more than 3.5 million people worldwide and has caused more than 250,000 deaths from COVID-19 since its discovery late last year.

The report was based on a computational analysis of more than 6,000 coronavirus sequences from around the world, compiled by the Global Influenza Data Sharing Initiative, a public-private organization in Germany. Time and time again, the analysis found that the new version was in transition to become dominant.

The Los Alamos team, assisted by scientists from Duke University and the University of Sheffield in England, identified 14 mutations. Those mutations occurred among the nearly 30,000 base pairs of RNA that other scientists say make up the coronavirus genome. The report’s authors focused on a mutation called D614G, which is responsible for the change in the virus’s spikes.

“The story is troubling, as we see a mutated form of the virus emerging very rapidly, and during the month of March it became the dominant pandemic form,” study leader Bette Korber, a computer biologist in Los Alamos, wrote on her page. From Facebook. “When viruses with this mutation enter a population, they quickly begin to take over the local epidemic, making them more transmissible.”

While the Los Alamos report is highly technical and dispassionate, Korber expressed some deep personal feelings about the implications of the finding in his Facebook post.

“This is difficult news,” wrote Korber, “but please do not be discouraged by that.” Our team at LANL was able to document this mutation and its impact on transmission only due to a massive global effort by clinical people and experimental groups, making the new virus sequences (SARS-CoV-2) in their local communities so available fast as they possibly can. “

Korber, a Cal State Long Beach graduate who earned a doctorate in chemistry from Caltech, joined the laboratory in 1990 and focused much of her work on an HIV vaccine. In 2004, he won the Ernest Orlando Lawrence Award, the highest recognition from the United States Department of Energy for his scientific achievements. She contributed a portion of the financial award to help establish an orphanage for young AIDS victims in South Africa.

The report contains regional breakdowns of when the new virus strain emerged and how long it took to become dominant.

Italy was one of the first countries to see the new virus in the last week of February, around the same time that the original strain appeared. Washington was one of the first states to be hit with the original strain in late February, but by March 15 the mutated strain dominated. The original virus hit New York around March 15, but within days the mutant strain took over. The team did not report results for California.

Scientists at major organizations working with a vaccine or medication have told the Times that they are relying on initial evidence that the virus is stable and unlikely to mutate like the influenza virus, requiring an new vaccine every year. The Los Alamos report could override that assumption.

If the pandemic doesn’t decrease seasonally as the weather warms, the study warns, the virus could undergo more mutations even when research organizations prepare the first medical treatments and vaccines. Without taking the risk now, the effectiveness of vaccines could be limited. Some of the developing compounds are supposed to adhere to or disrupt the spike. If designed based on the original version of the spike, they may not be effective against the new strain of coronavirus, the study authors cautioned.

“We cannot afford to go blind while we pass vaccines and antibodies to clinical trials,” Korber wrote on Facebook. “Please be encouraged to learn that the global scientific community is in this, and we are cooperating with each other in a way that I have never seen before … in my 30 years as a scientist.”

David Montefiori, a Duke University scientist who worked on the report, said he is the first to document a mutation in the coronavirus that appears to make him more infectious.

Although the researchers still don’t know the details of how the mutated spike behaves inside the body, it is clearly doing something that gives it an evolutionary advantage over its predecessor and is fueling its rapid spread. A scientist called it a “classic case of Darwinian evolution”.

“D614G is increasing in frequency at an alarming rate, indicating a fitness advantage over the original Wuhan strain that allows for faster spread,” the study said.

It is still unknown whether this mutant virus could explain regional variations in the intensity with which COVID-19 is affecting different parts of the world.

In the United States, doctors independently began to question whether the new virus strains could explain the differences in how it has infected, sickened, and killed people, said Alan Wu, a UC San Francisco professor who runs clinical chemistry labs and toxicology. at the San Francisco General Hospital.

Medical experts have speculated in recent weeks that they were seeing at least two strains of the virus in the United States. One prevalent on the east coast and one on the west coast, according to Wu.

“We are looking to identify the mutation,” he said, noting that his hospital has had only a few deaths out of the hundreds of cases it has treated, which is “quite a different story than what we are hearing in New York.”

The Los Alamos study does not indicate that the new version of the virus is more lethal than the original. People infected with the mutated strain appear to have higher viral loads. But the authors of the University of Sheffield study found that among a local sample of 447 patients, hospitalization rates were nearly the same for people infected with either version of the virus.

Even if the new strain is not more dangerous than the others, it could complicate efforts to control the pandemic. That would be a problem if the mutation makes the virus so different from previous strains that people who have immunity to them would not be immune to the new version.

If that’s the case, it could make “people susceptible to a second infection,” the study authors wrote.

It is possible that the mutation will change the peak in some way that helps the virus evade the immune system, said Montefiori, who has worked on an HIV vaccine for 30 years. “It is hypothetical. We are seeing it very hard. “

Current news about Coronavirus

Fight against coronavirus: full coverage

[ad_2]