[ad_1]

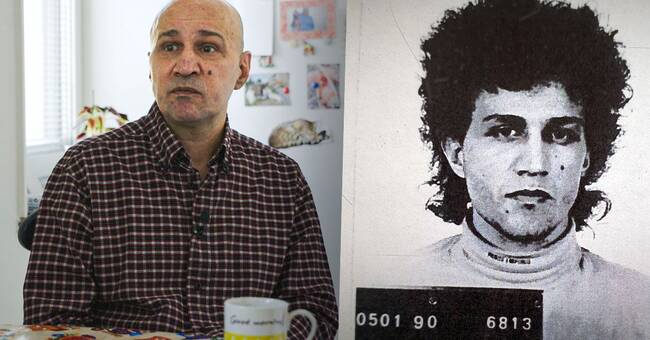

On September 12, 2006, Mahmoud Reza Beirani will perform at Norrbro in Stockholm. In his hand he holds an ax and around his neck hangs a trap. Threatens to kill himself.

The police block the area and call the negotiators. Passersby perceive the situation as threatening, but no one is hurt. Beirani then says that he does it to be seen.

– All day I screamed that “Here I am. I exist I exist You can’t go on for so many years and say no, you don’t exist. I exist I’m here.”

Late at night he gives up and is taken to the forensic psychiatric clinic in Säter. But the story begins much earlier, in March 1987, when Beirani arrived in Sweden from Iran.

Convicted of drug trafficking

He arrives without a passport or identity documents, states his real name and says he is seeking asylum. That same year, he was granted a permanent residence permit, learned Swedish at SFI and trained as a turner.

But Beirani is starting to abuse drugs. In 1993, he was indicted with ten other people in a drug scandal in which he admits that he used and sold heroin to smoke. He is sentenced to seven and a half years in prison and deportation for life.

In October 1998, he was released on parole and airlifted with two officials from the transport service of the Swedish Prison and Parole Service to Iran. He says he’s looking forward to coming home.

– He had an open smile when we went to Iran. He was joking with two government officials up to Iran. I wanted to go home and I wanted to live the rest of my life there, says Beirani.

Police: Destroyed the whole case.

But it won’t. Beirani, who still has no identity documents, is told to get off the plane alone. He ends up being escorted back by Iranian border guards.

– They just grabbed me by the neck and took me to the plane, threw me and said “send away,” says Beirani.

The assignment review meets with the former head of Aliens Rotel in Norrköping, Tore Persson, who is highly critical of the way the deportation was handled.

– I think it’s actually the decision they made on board the plane, to stay there and not go ahead and negotiate, that has ruined the whole thing, says Tore Persson.

The two officials who escorted Beirani have declined to be interviewed by Assignment Review.

For several years, Tore Persson has been working towards the expulsion of Beirani. He is trying to get the Iranian embassy to confirm his identity and organize the necessary travel documents, but the embassy is constantly demanding new information to do so.

Meanwhile, Beirani is in custody. After eight months, he is released, but can only stay in the municipalities of Vadstena and Motala for two years. Just before his retirement, Tore Persson gives up and supports a Beirani clemency request.

– He did not have permission to be in the country, but he had to be in the country. He didn’t get a chance to get out of here and he didn’t get a chance to get a job or anything.

“It touched me very hard”

The government rejects Tore Persson’s request. Years go by and Beirani’s mental health deteriorates, she loses weight and takes sedative pills. After attempting to kill himself, he spends time in a psychiatric clinic.

The former Vadstena pastor, Torbjörn Ahlund, is involved in the case:

– He did not receive papers, he was not allowed to work and yet he had to stay, because it was not possible to return him. I was very touched.

It has been 22 years since the failed expulsion of Mahmoud Reza Beirani. He agrees that he was the one who put himself in the situation when he committed his crime.

– I didn’t know what it would be like. If I had guessed it, all the mistakes would be corrected. It’s like they say, it’s easy to be retrospective, he says himself.

Having previously participated in the expulsion, Beirani is no longer willing to return home. He says he has no connection to Iran and only has a few distant relatives left. He is concerned about what could happen if the authorities are reported, in a country where a serious drug offense can be punishable by death and prisoners being tortured, who once sold heroin in Sweden.

A “quite positive” forecast

Today she lives with her friend Karolina in Motala. Every month, he visits the social services that pay for financial assistance as Beirani, according to them, meets the requirements to be entitled to support.

Doesn’t he send double signals that a part of society has decided he should be kicked out of here?

– I can understand what you think and that’s how it looks right now with the regulations. What we have to relate to is the right to subsistence, says Lilane Egnell.

The Swedish authorities have tried since 1998 to establish Beirani’s identity with the help of the Iranian embassy, without success. But the border police responsible for the deportation say it has a “pretty positive prognosis” and believes it should be possible to implement.

Is it common that it takes up to 22 years?

– I’d say it’s not common. Normally, we execute people already on the day of their release, says Ulrika Johansson, head of the border police in the Eastern Region.

After Assignment Review interviewed the Iranian embassy in Sweden, they announced that they have now established Beirani’s identity. Watch the interview and read more about Iran’s attitude towards deportations. here.