Predators in the Okavango Delta region in Botswana are plagued by attacks by lions and other predators, asking farmers to take revenge by killing the predators. An alternative nonlethal technique involves painting eyes on the butts of cattle to trick preachers such as lions into thinking they have been spotted by their intended prey. It’s called the “Eye-Cow Project”, and a recent paper published in the journal Communications Biology provides some solid empirical evidence for the practice. There are now practical manuals for using the “eye-cow” technique available in both English and Setswana, so that farmers can try it for themselves.

Neil Jordan, a conservation biologist at the University of New South Wales in Australia, came up with the idea several years ago while doing fieldwork in Botswana. Local farmers killed a few lionesses in retaliation for the prey of their cows, and Jordan wanted to come up with a non-lethal alternative. The African lion population has dropped significantly from more than 100,000 in the 1990s to somewhere between 23,000 and 39,000 in 2016 – many of which have to do with revenge killings.

Jordan knew that butterfly wings with sporty eye patterns are known to protect prey birds, and are also found in certain fish, molluscs, amphibians and birds, although such patterns were not observed in mammals. He also discovered that lumberjacks in Indian forests were known to wear masks on the back of their heads to discourage tigers hunting prey. He had spotted a lion stalking an impala, and noticed that the predator was hunting when the prey spotted it. Lions are horse hunters, Jordan reasoned, and decided to test his “detection hypothesis” that painting eyes on the butts of cows would discourage predatory behavior from the local lion population.

The Botswana Predator Conservation Trust (BPCT) has agreed to work with Jordan on the project, along with a local farmer, for a ten-week pilot study. Jordan and the farmer painted the eyes of one-third of a herd of 62 cattle, and took a head count when the cattle returned to the fold each night to see how many were left. During that period, only three cows were killed, none of which had eyes painted on their butts. All painted cows survived.

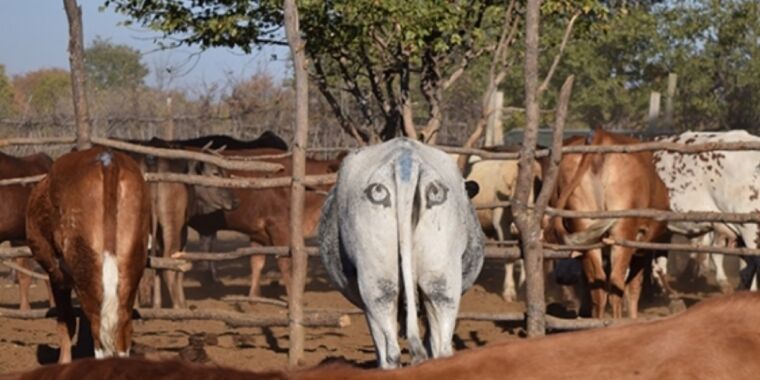

Sure, it was a small sample size, but those results were encouraging to persuade Jordan to conduct a more ambitious study over the last four years. His team worked with local farmers in the Okavango Delta region, painting the livestock in 14 herds (a total of 2,061 animals). They used acrylic paint (black and white as well as yellow), applied with shoe stencils in the shapes of the inner and outer “eyes”. The colors were chosen “because of their highly contrasting and aposematic features, simply in natural settings for anti-predator signal,” the authors wrote.

Roughly one third of the cattle in each herd received the eye patterns, one third received simple cross points, and one third were not painted at all. The results confirmed Jordan’s preliminary findings. Bovine animals with the painted eyes on their trunks were significantly more likely to survive than those cows that had crosses on their butts and that were not painted at all. But the authors were surprised to find that even the painted crosses had some survival advantage over the unpainted cattle. During the four-year study, 15 (out of 835) were not painted and four (out of 543) cross-colored cattle were killed by lions; not one of the 683 animals with painted eyes was killed.

“To our knowledge, our research is the first time it has been shown that large mammals scare off predators,” said co-author Cameron Radford, a student at the University of South Wales. “Previous work on mammalian responses to eye patterns has generally supported the detection hypothesis. We think this may suggest the presence of an inherent reaction to eyes that could be exploited to change behavior in practical situations, such as conflicts for human-wild animals, and reduce criminal activity in humans. “

There are a few caveats. First, Jordan acknowledged that there were always unmarked cattle in the herd for their experiments as controls – what he called “proverbial sacrificial lambs”. It is not clear whether applying painted eyes to cow herds would be as effective if all the cows in the herd were painted. He suggests that farmers apply the markets to the most valuable livestock in the herd if the best approach to future research can be done. Second, there is the question of habit: if predators will eventually become accustomed to the painted eyes and learn to ignore them as a limitation.

“Protecting livestock from wild carnivores – and carnivores themselves – is a major and complex issue that is likely to require the application of a suite of tools, including practical and social interventions,” Jordan said. “The eye cow technique is one of a number of tools that can prevent conflict with meat farming. No single tool is likely to be a silver bullet. In fact, we need to do much better than a silver bullet if we are to co-exist successfully. cattle and large carnivores. But we hope this simple, low-threshold, non-lethal approach could reduce the cost of co-existence for those farmers who carry the hull. “

DOI: Communications Biology, 2020. 10.1038 / s42003-020-01156-0 (About DOIs).