Black holes are not supposed to flash light. It’s right there in the name: black holes.

Even when they collide with each other, massive objects are supposed to be invisible to astronomers’ traditional instruments. But when scientists spotted a black hole collision last year, they also saw a strange flash of the crash.

On May 21, 2019, Earth gravitational wave The detectors picked up the signal from a pair of colliding massive objects, sending cascading waves through space-time. Later, an observatory called the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) caught an explosion of light. When scientists looked at the two signals, they realized they were both coming from the same patch of sky, and researchers began to wonder if they had seen the rare visible black hole collision.

“This detection is extremely exciting,” Daniel Stern, co-author of a new study on the discovery and an astrophysicist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, said in a statement from NASA. “There is a lot we can learn about these two fused black holes and the environment they were in based on this signal that they inadvertently created.”

Related: Scientists have just found the largest neutron star (or smallest black hole) yet in a strange cosmic collision

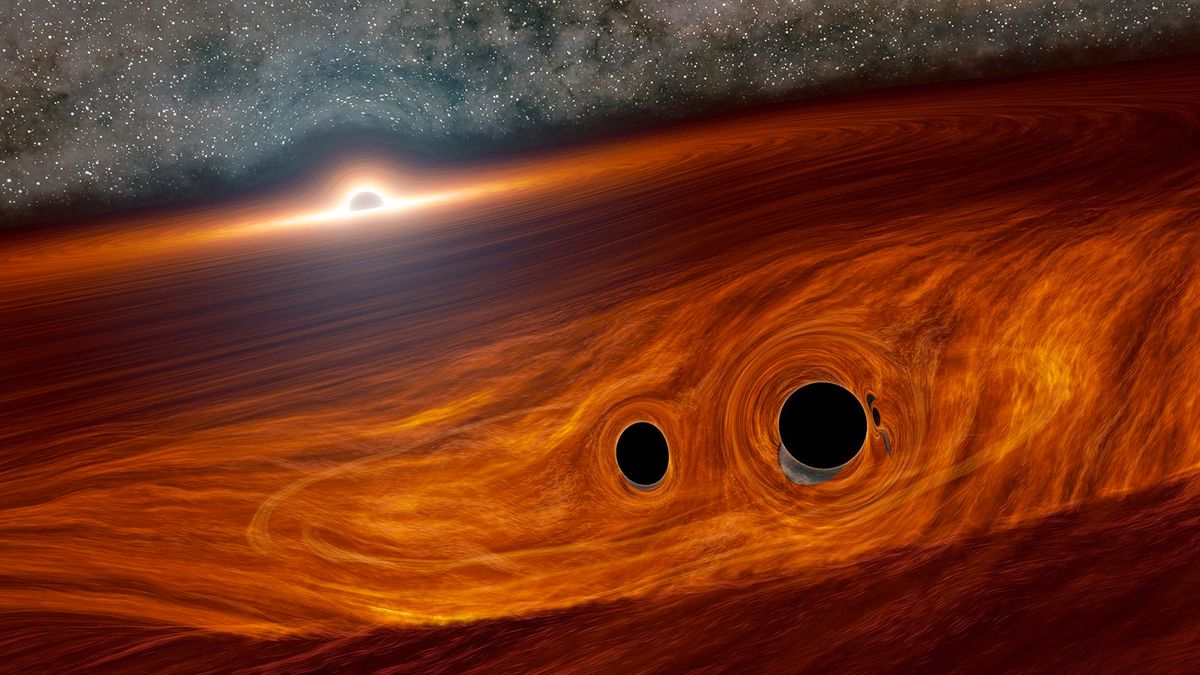

This is what scientists think happened in this strange case. The two merging black holes were enclosed in the disk surrounding a quasar, a supermassive black hole that fires blasts of energy.

“This supermassive black hole was bubbling for years before this most abrupt flare,” Matthew Graham, Caltech astronomer and project scientist for ZTF, he said in a university statement.

That in itself is not so strange, according to his colleague. “Supermassive black holes like this erupt all the time,” co-author Mansi Kasliwal, an astronomer at Caltech, said in the statement. “They are not silent objects, but the timing, size, and location of this flare were spectacular.”

Scientists suspect, based on the pairing of gravitational waves and light, that the flare arose from two small black holes that merged within the accretion disk of the supermassive black hole. The incredibly strong gravity of the supermassive black hole affects the smallest things on the disk, even other black holes.

“These objects swarm like angry bees around the monstrous queen bee in the center,” said co-author KE Saavik Ford of the New York City University Graduate Center, Borough of Manhattan Community College and the American Museum of History Natural. statement. “They can briefly find gravitational partners and pair up, but they generally lose their partners quickly in the crazy dance. But in the disk of a supermassive black hole, the flowing gas turns the swarm’s mosh pit into a classic minuet, organizing black holes so they can be paired. “

The flash of light does not come from the merger itselfscientists think. Instead, the force of the fusion sends the now slightly larger black hole flying through the surrounding gas in the accretion disk of the supermassive black hole. The gas, in turn, produces the flare after a delay of days or weeks, according to theory. In the case of this event, scientists detected the eruption approximately 34 days after the gravitational wave signal.

The researchers said that this does not guarantee that this explanation fits what happened.

“The eruption occurred on the correct time scale, and at the correct location, to coincide with the gravitational wave event,” said Graham. “We conclude that the eruption is likely the result of a merger of black holes, but we cannot completely rule out other possibilities.”

The results are described in a paper published Thursday (June 26) in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Email Meghan Bartels at [email protected] or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us On twitter @Spacedotcom and in Facebook.