Scientific ‘Red Flag’ reveals new clues about our galaxy

Find out how much energy permeates the center of the Milky Way – a discovery reported in the July 3 issue of the magazine Scientific advances “It could give new clues to the fundamental source of our galaxy’s power,” said L. Matthew Haffner of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University.

The nucleus of the Milky Way vibrates with hydrogen that has been ionized or stripped of its electrons so it has plenty of energy, said Haffner, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Embry-Riddle and co-author of the Scientific advances paper. “Without a continuous source of energy, free electrons generally meet and recombine to return to a neutral state in a relatively short period of time,” he explained. “Being able to see ionized gas in new ways should help us discover the types of sources that might be responsible for keeping all of that gas energized.”

University of Wisconsin-Madison Dhanesh Krishnarao (“DK”) graduate student, lead author of Scientific advances paper, collaborated with Haffner and professor Bob Benjamin of UW-Whitewater, a leading expert on the structure of stars and gas in the Milky Way. Before joining Embry-Riddle in 2018, Haffner worked as a research scientist for 20 years at the University of Washington, and continues to serve as principal investigator for the Wisconsin H-Alpha Mapper, or WHAM, a Chile-based telescope that was used for the team. last study

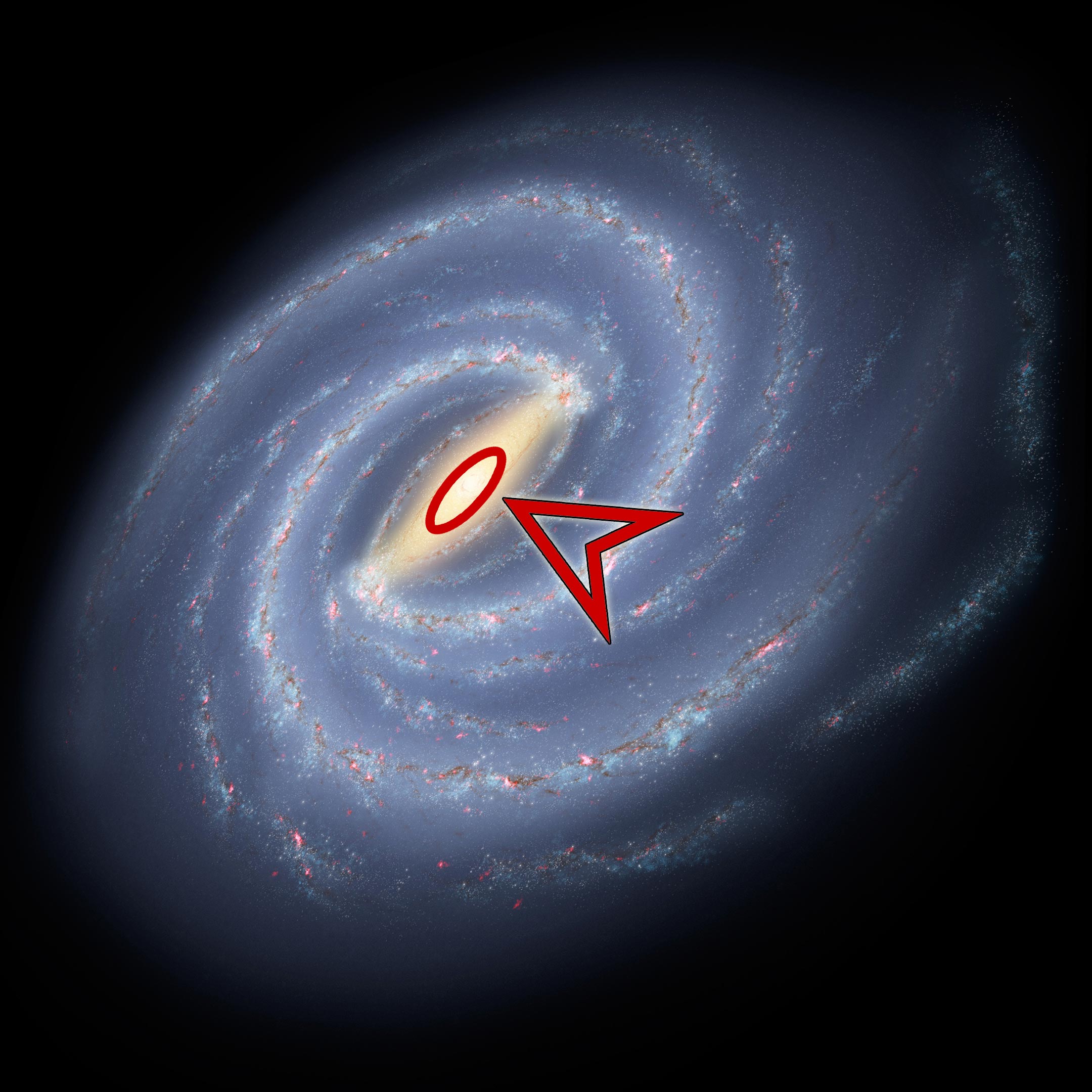

To determine the amount of energy or radiation at the center of the Milky Way, the researchers had to look through a sort of tattered dust cover. Packed with more than 200 billion stars, the Milky Way is also home to dark patches of dust and interstellar gas. Benjamin was looking at the WHAM data from two decades when he saw a scientific red flag, a peculiar shape protruding from the dark and dusty center of the Milky Way. The rarity was ionized hydrogen gas, which appears red when captured through the sensitive WHAM telescope, and was moving in the direction of Earth.

The position of the feature, known to scientists as the “Tilted Disc” because it appears to be tilted compared to the rest of the Milky Way, cannot be explained by physical phenomena known as galactic rotation. The team had a rare opportunity to study the protruding inclined disk, released from its irregular dust cover, using optical light. Typically, the tilted disk should be studied using radio or infrared light techniques, which allow researchers to make observations through dust, but limit their ability to learn more about ionized gas.

“Being able to make these measurements with optical light allowed us to compare the Milky Way nucleus with other galaxies much more easily,” said Haffner. “Many previous studies have measured the quantity and quality of ionized gas at the centers of thousands of spiral galaxies throughout the universe. For the first time, we were able to directly compare the measurements of our galaxy with that large population. “

Krishnarao took advantage of an existing model to try to predict how much ionized gas should be in the emitting region that had caught Benjamin’s attention. Raw data from the WHAM telescope allowed him to refine his predictions until the team had an accurate three-dimensional image of the structure. Comparing other colors of visible light from hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen within the structure gave the researchers more clues about its composition and properties.

At least 48 percent of the hydrogen gas in the inclined disk in the center of the Milky Way has been ionized by an unknown source, the team reported. “The Milky Way can now be used to better understand its nature,” said Krishnarao.

The gaseous and ionized structure changes as it moves away from the center of the Milky Way, the researchers reported. Previously, scientists only knew about the neutral (non-ionized) gas located in that region.

“Near the core of the Milky Way,” Krishnarao explained, “the gas is ionized by the newly formed stars, but as you move away from the center, things become more extreme and the gas becomes similar to a class of galaxies. called LINERs or regions of low emission of ionization (nuclear) “.

The researchers found that the structure seemed to move toward Earth because it was in an elliptical orbit inside the spiral arms of the Milky Way.

LINER-type galaxies, such as the Milky Way, account for about a third of all galaxies. They have centers with more radiation than galaxies that are only forming new stars, but less radiation than those whose supermassive black holes are actively consuming a tremendous amount of material.

“Before this WHAM discovery, the Andromeda galaxy was the closest LINER spiral to us,” said Haffner. “But it is still millions of light years away. With the core of the Milky Way just tens of thousands of light-years away, we can now study a LINER region in more detail. Studying this extended ionized gas should help us learn more about the current and past environment at the center of our galaxy. “

Next, researchers must discover the energy source at the center of the Milky Way. Being able to classify the galaxy based on its radiation level was an important first step toward that goal.

Now that Haffner has joined Embry-Riddle’s growing Astronomy and Astrophysics program, he and his colleague Edwin Mierkiewicz, an associate professor of physics, have big plans. “In the coming years, we hope to build WHAM’s successor, which would give us a clearer picture of the gas we are studying,” said Haffner. “Right now, our map ‘pixels’ are twice the size of the full moon. WHAM has been a great tool in producing the first sky-wide study of this gas, but now we are hungry for more details. “

In a separate investigation, Haffner and colleagues reported earlier this month on the first visible light measurements of “Fermi Bubbles,” mysterious columns of light projected from the center of the Milky Way. That work was presented at the American Astronomical Society.

###

Reference: “Discovery of diffuse optical emission lines from the inner galaxy: evidence of gas similar to ER LI (N)” July 3, 2020 Scientific advances.

DOI: 10.1126 / sciadv.aay9711

Research described in Scientific advances the document “Discovery of Diffuse Optical Emission Lines from the Inner Galaxy: Evidence for Gas Similar to ER LI (N)”, was supported in part by the National Science Foundation for WHAM development, operations and science activities, including grants AST-0607512, AST-1108911 and AST-1714472/1715623; POT grant NNX17AJ27G; and the IDEX Paris-Saclay grant ANR-11-IDEX-0003-02.