When the flu pandemic hit the United States in 1918, most cities responded with measures that included closing schools.

However, three cities, New York, Chicago, and New Haven, Connecticut, promised to remain open.

Schools had extensive public health programs and argued that keeping students in school was “an opportunity to implement public health strategies for school medical inspection and intensified disease surveillance,” according to a public health report published in 2010.

Now, more than a century later, when society faces the same question of whether to reopen schools during a pandemic, experts warn that what allowed those three cities to remain open in 1918 is no longer feasible.

Dr. Howard Markel, co-author of the report and distinguished professor of medical history at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, told ABC News that the situations “differ in a billion ways,” that is, that they still There is little known about the coronavirus and there is no longer an emphasis on public health in schools.

“There was a system in place that has been dismantled for a long time,” said Markel.

In New York City, the then Commissioner of Health, Dr. Royal S. Copeland, had relied almost entirely on isolation and quarantine to stop the spread of the virus, but eventually Dr. S. Josephine Baker, director of the Department of Health Office of Child Hygiene, according to the 2010 public health report.

Baker, a leading reformer in the progressive era, when officials and experts placed more emphasis on expanding public health and education programs, believed that many students would be safer at school than ever.

At the time, 75% lived in houses with overcrowded and unhealthy conditions that made it easier for infections to spread, according to the report.

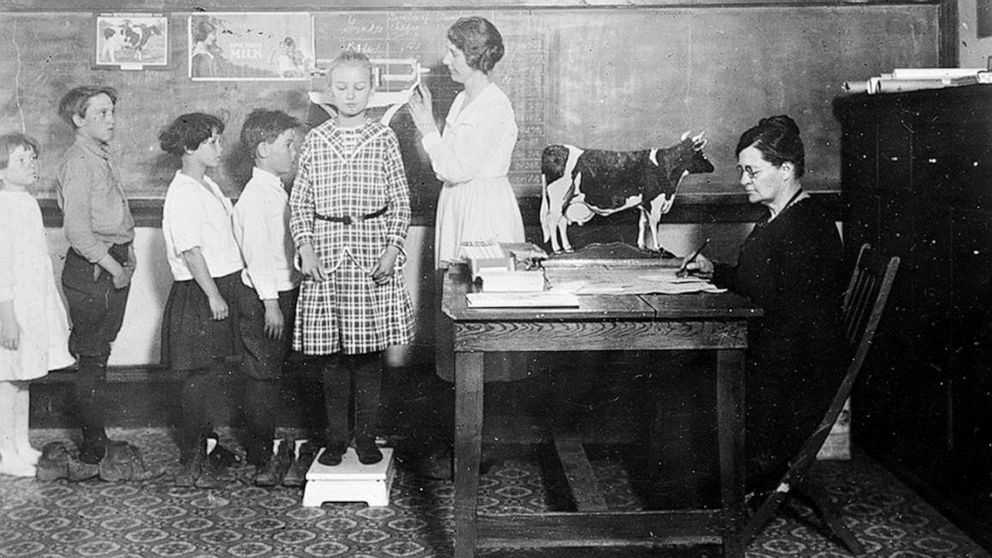

In schools, students underwent routine inspections, the report noted. Teachers looked for signs of a respiratory condition, such as a runny nose, red eyes, sneezing, or cough.

If the students showed any symptoms, they were transferred to an isolation room where they were inspected by a health professional and, if they had a fever, they were sent to their homes or to a hospital if their home was a critical point of spread.

In Chicago, the city’s health commissioner, John Dill Robertson, believed that schools could build their “well-developed school medical inspection program,” according to the public health report.

Robertson coordinated with Dr. C. St. Claire Drake, the state’s director of health, regularly to develop regulations and action plans. School health officials and nurses also visited the homes of the absent students and informed families of the proper procedures for isolation and care.

Chicago suffered more absenteeism than New York City, which Robertson attributed to “fluphobia.”

New Haven Health Officer Dr. Frank W. Wright was also one of those who urged schools to remain open.

Wright argued that children “would be safer in well-ventilated schools where doctors and nurses worked full time to identify sick children and send them home to receive appropriate care,” according to the 2010 report.

In early October, about a month after the pandemic, health and school officials agreed that children should stay in school to prevent them from congregating elsewhere unsupervised and to minimize their exposure to infected adults.

Markel and another co-author of the report, Dr. Alexandra Stern, noted that the influenza outbreak and the new coronavirus outbreak are not epidemiologically the same.

Although the 1918 outbreak was severe, health experts knew much more about the flu than they do now about the new coronavirus, and its effects on children.

A recent study from South Korea found that children younger than 10 years old transmitted COVID-19, the disease caused by the respiratory virus, to others much less often than adults, although the risk is not zero. According to the study, people ages 10 to 19 transmit the virus at about the same rate as adults.

Another study conducted in the United Kingdom found that children under the age of 18 were not as negatively affected by COVID-19 as adults.

Markel put it simply: “The key word in this new coronavirus is ‘novel.’ It is new.”

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has influenced the reopening of schools. Originally, the federal agency warned of the risks of reopening schools and issued recommendations. But on Thursday, two weeks after President Donald Trump demanded the reopening of schools, the CDC changed its tune and released statements about children who are not at high risk of becoming seriously ill, though their original guidance still remained in place. Web.

Markel also said that detailed responses such as those available in 1918 would be unlikely or simply impossible today because so much funding for public health programs has been cut.

“In recent decades, financial cuts to public education have severely impacted public health programs, reducing the number of school nurses and resources for activities such as physical education,” according to the 2010 study.

Stern called most public schools “woefully inadequate,” and most had “a rotating nurse who would move between five public schools.”

“The bottom line is that the public health infrastructure that was built in schools as they expanded in the early 1900s has been largely destroyed and dismantled,” Stern said.

As of 2018, based on the most recent data available on school nurses, there were 95,776 working full-time in the U.S., according to the National Association of School Nurses. With about 50.8 million students in public schools, this is one nurse for every 530 students.

Statistics like this show how difficult it would be for routine medical inspections, let alone practices adopted in Chicago, such as the way nurses visited the homes of absent students.

Markel and Stern, however, recognized the complexity of the problem and said that for many children, school is not just a place for education.

“The best reasons, or the most compelling reasons, for wanting children to go to school is that they live in an unsafe environment and school nutrition,” said Markel, although he noted that some school districts have promised to deliver meals.

He thinks that school “is not a good idea at the moment.”

Stern felt the same, saying there are “so many unanswered questions.”

“And when there are unanswered questions about a deadly virus,” added Stern, “you could argue that it makes more sense to follow the precautionary principle, which is ‘Do the least harm.'”

.