For years, scientists have been trying to track down an extremely rare “boomerang” earthquake. Well, they’d taken one into the ocean for the first time – and it’s even more bizarre than they expected.

Earthquakes are the result of rocks breaking on a fault, which is a boundary between two plates. An earthquake “boomerang”, also known as a “rear-end supershear rupture”, means that the rupture moves away from the initial crack before returning at an even faster rate, scientists said.

Great earthquakes are capable of destroying buildings and triggering tsunamis, so understanding how they work is necessary to assess potential hazards and implement warning systems for future shocks.

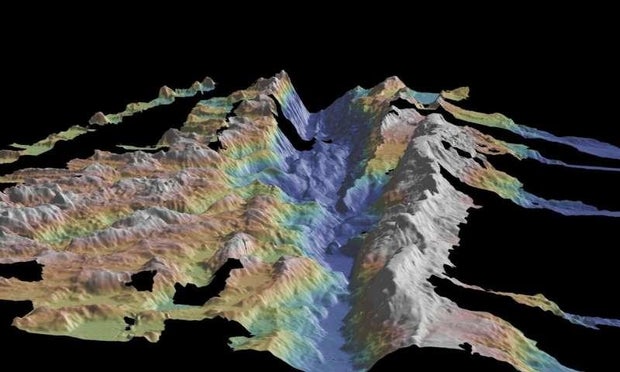

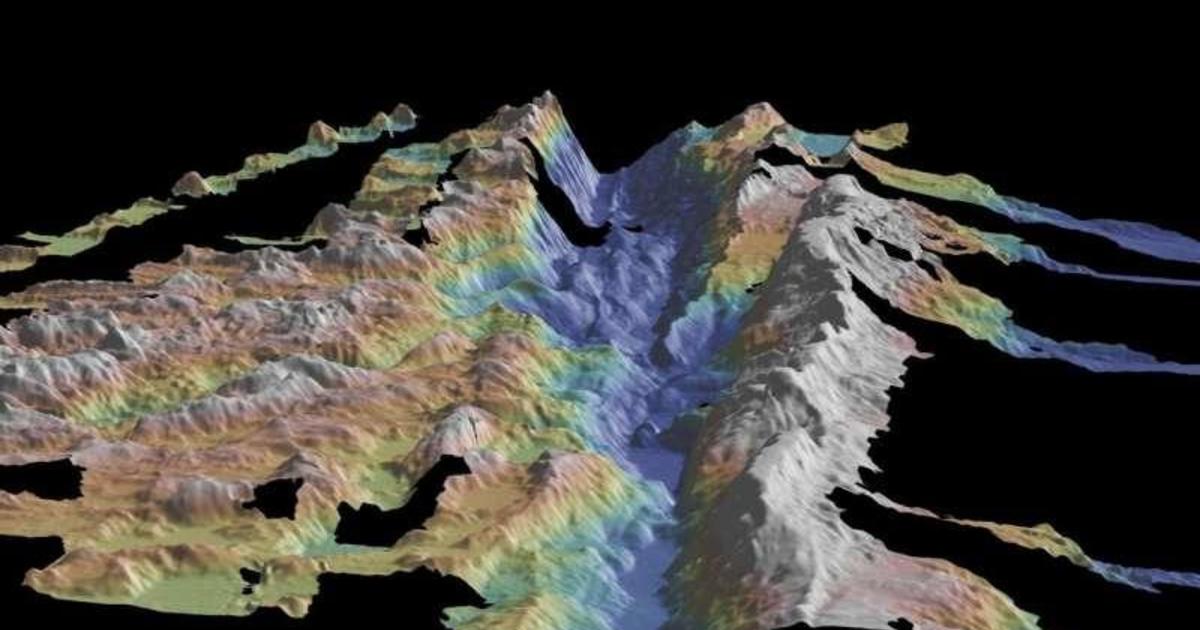

According to a new study in the journal Nature Geoscience, a team led by scientists from the University of Southampton and Imperial College London successfully carried out a magnitude 7.1 earthquake on August 29, 2016. It ran along the fracture zone of the Romanche, a 560-mile fault line below the Atlantic Ocean at the equator, between Brazil and Africa.

Scientists say that large – significant magnitude 7 or higher – shakes are difficult to study because they often set up a series of chain reactions along complex networks of faults. Faults under the ocean have simple shapes, but they lie far away from seismometer networks on land, so an underwater network of seismometers is needed.

Researchers said the quake traveled in one direction between the South American and African tectonic plates, and then boomeranged back to the beginning at ultra-fast speeds – breaking the “seismic sound barrier” – a sonic boom of sorts.

Hicks et al

An analysis showed that the quake had two distinct phases. The fracture first traveled upwards and to the east, before suddenly returning and moving west to the center of the fault at a rapid velocity of 3.7 miles per second.

Scientists are not exactly sure how this happened, but they believe that the first phase somehow exposes aggressive aggressors.

Only a handful of boomerang earthquakes have ever been recorded – the phenomenon has been theoretical to this day.

“Although scientists have found that such a mechanism for reversible fracture is possible from theoretical models, our new study provides some of the clearest evidence for this enigmatic mechanism occurring in a real error,” leads author Dr. Stephen Hicks, from the Department of Earth Sciences and Engineering at Imperial College London, said in a press release.

“Even though the error structure seems simple, the way the earthquake grew was not, and this was in stark contrast to how we expected the earthquake to look before we started analyzing the data.”

Scientists said that if a similar type of shaking occurred on land, it would drastically affect the amount of ground shaking – and possibly widen the affected area. If you follow more boomerang shakes, researchers would be better able to predict and assess the dangers of such events, and improve impact forecasts.

.