“We do not even think about” the decline in the purchasing power of the dollar – and therefore the purchasing power of labor.

By Wolf Richter for WOLFSTREET.

A supply shock and a demand shock came together during the Pandemic, and it produced chaos in the price environment. There was a sudden drop in demand in some segments of the economy – restaurants, petrol, jet fuel, for example – and an increase in demand in other segments, such as eating at home, and everything to do with the -commerce, including transportation services aimed at it.

These shifts came along with supply chain and supply chain disruptions that were not prepared for the major shifts, leading to deficits in some parts of the economy – the supply shock. There were empty shelves in stores, while product stepped up with no buyers in other parts of the economy.

The sectors surrounding petrol, jet fuel, and diesel fuel – oil and gas drilling, equipment manufacturers, transportation services, refineries, etc. – were thrown into turmoil when demand disappeared, leading to a total collapse in energy prices. In April, at a bizarre moment in the history of the oil industry, the price of the US benchmark crude WTI came to negative – 37 dollars per barrel.

Since then, the price of crude oil has risen sharply (now to a positive + $ 41 per barrel), as demand for gasoline has returned to near normal, while demand for jet fuel remains in column mode as people drive around to go on vacation, instead of flying, and when business travel is essentially closed.

As a result, in a few months, all inflation data went into horseback, with some prices falling and others spike. This is now being worked out of the system.

Energy prices are up from March and April, but remain below last year. Gasoline prices jumped 12.6% in June to May and by another 5.6% in July to June, but are still down 20.2% from July last year, according to the Consumer Price Index report. tomorrow by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Electricity services rose 0.3% in July, following a sharp decline in the previous two months.

Prices of food eaten at home, after rising from March to June during the shifts and the period of empty shelves, fell by 1.1% in June from July, but were still up 4.6% from last year year. More on the main categories in a moment.

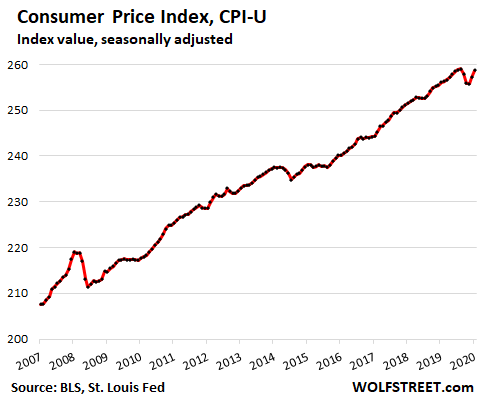

Total inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index for Urban Consumers (CPI-U) jumped 0.6% in July from July to June, after jumping 0.6% from May in June, and the decline exchanged in March to May. Compared to July 2019, CPI was up 1.0%, still held back by the 20.2% year-over-year decline in energy prices. The month-on-month increases of June and July of 0.6% each were the largest two since 2009.

The CPI excluding food and energy rose 0.6% in July from June and was 1.6% up from July last year.

When we say that the CPI increased by 0.6% from June in July, we mean that it went from an index value of 257.2 to an index value of 258.7. We get this chart that looks like progress, as something good has happened, with a fairly consistent uptrend from bottom left to top right, kind of like a stock market chart, and the Fed and economist want this line, and lines of other inflation indices, to climb steeper, and they take pride in doing so when it does:

But the Bureau of Labor Statistics also offers the corollary index, the “Purchasing Power of the Consumer Dollar.” And it just hit a new all-time ever low. Note on purchasing power recovery during the financial crisis, when consumers could actually buy a little more with their labor for a few quarters:

If the Fed wants to increase consumer price inflation, it does reduce the purchasing power of the consumer dollar.

At the moment, the Fed is very impatient about purchasing the purchasing power of the dollar. To communicate this, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell continues to repeat so eloquently that the Fed does not “even think about thinking” about the decline in the purchasing power of the dollar as it accelerates.

A decline in the purchasing power of the consumer dollar means a decline in the purchasing power of labor. And consumers (who are in their real-life jobs) need a corresponding increase in wage inflation.

For employers who can raise prices but do not have to raise wages, it means “cheaper labor” – and this has been one of the major problems in the US economy for decades among the lower 40% of workers who deliver this cheaper labor.

So for consumers who earn their money by working, inflation of consumer price means that the purchasing power of their labor is diminished. Goods and services are more difficult to pay, and their wages are being pushed up by rising costs, and there is less money left to make mortgage payments and other debt payments.

Inflation of consumer prices, given the wage environment by several decades, means the further impoverishment of the people in the lower income categories, and means making debt payments harder – not easier.

These people want to wage inflation (pay more for the same work) to compensate them for price inflation, but wage inflation is anathema to Corporate America and the Fed.

Rising prices make debt payments easier for only those who can raise prices: Companies, in particular Corporate America where price power and debt are concentrated.

Inflation by category.

Here are the changes in the consumer price index for the main categories. The second column shows the relative weight of the line item in the total CPI. The biggie is “services less energy services” which weighs 59.6% in the index. It includes two sub-biggies: “shelter” which includes horse and equivalent of owner of hair, which make up one third of CPI, and “medical care”, with a relative stake of 7.4% in CPI.

The third column shows the change in prices in July compared to July last year. The three columns on the right show month-on-month price changes, with the sixth column showing the current change in July of June (if your smartphone cuts the right part of the table and you do not see six columns, turn your device into landscape mode):

| Category expenses | % weight | % YOY July | % Apr-May | % May-Jun | % Jun-Jul |

| Food | 14.3 | 4.1 | 0.7 | 0.6 | -0.4 |

| Food at home | 8.0 | 4.6 | 1.0 | 0.7 | -1.1 |

| Cereals and bakery products | 1.0 | 2.8 | -0.2 | 0.4 | -0.4 |

| Meats, poultry, fish, eggs | 1.9 | 8.4 | 3.7 | 2.0 | -3.8 |

| Milk and related products | 0.8 | 4.4 | 1.0 | -0.4 | -0.8 |

| Fruits and vegetables | 1.4 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Non-alcoholic beverages | 0.9 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | -0.5 |

| Other food at home | 2.0 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 0.2 | -0.2 |

| Food away from home | 6.3 | 3.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Energy | 6.1 | -11.2 | -1.8 | 5.1 | 2.5 |

| Energy Commodities | 2.9 | -20.2 | -3.5 | 11.7 | 5.3 |

| Gasoline | 0.1 | -27.2 | -6.3 | 10.2 | 4.3 |

| Engine fuel | 2.8 | -20.3 | -3.5 | 12.0 | 5.5 |

| Petrol (all types) | 2.7 | -20.3 | -3.5 | 12.3 | 5.6 |

| Energy services | 3.2 | -0.1 | -0.5 | -0.2 | 0.0 |

| Electricity | 2.5 | -0.1 | -0.8 | -0.3 | 0.3 |

| Outdoor system (piped) gas service | 0.7 | -0.3 | 0.8 | 0.0 | -1.0 |

| Other goods | 20.7 | -0.5 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Apparel | 2.7 | -6.5 | -2.3 | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| New reds | 3.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.8 |

| Used cars and trucks | 2.5 | -0.9 | -0.4 | -1.2 | 2.3 |

| Commodities for medical care | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Alcoholic beverages | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.2 | -0.3 |

| Tobacco and smoked products | 0.6 | 5.2 | -0.2 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Services less energy services | 59.6 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Shelter (hair & equivalent of hair) | 33.5 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Medical care services | 7.4 | 5.9 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Transportation services | 5.0 | -3.7 | -3.6 | 2.1 | 3.6 |

| Engine maintenance and repair | 1.1 | 3.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | -0.1 |

| Motor car insurance | 1.5 | -1.9 | -8.9 | 5.1 | 9.3 |

| Loftline rates | 0.6 | -23.7 | -4.9 | 2.6 | 5.4 |

Enjoy reading WOLFSTREET and would you like to support it? Use ad blockers – I totally understand why – but want to support the site? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and ice tea cup to find out how:

Would you like to be notified by email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()