The chief of elections in the Detroit suburb of Rochester Hills, Michigan, a competitive softball player in her younger days, feels she has been pushed into the batting cage. This time, no one is giving Tina Barton a stick.

“It’s like he’s standing there with nothing to hit the balls,” said Barton. “Every day I go in and something new comes to me at great speed.”

Poll workers resign. An agitation of judicial decisions that throw electoral rules to riot. A COVID-19 outbreak at City Hall that could sideline your department at a critical time.

The viral pandemic has put the nation’s electoral system under stress with few precedents.

And while the figures in both parties rejected President Trump’s suggestion to postpone the November election when he flirted with the idea on Thursday, they have not provided the money officials like Barton need to prepare.

A few months ago, the House of Representatives approved $ 3.6 billion to help state and local election officials deal with an expected flood of mail ballots this fall, something that threatens to overwhelm election officials in the states where they vote for Mail is a relative novelty. Money has stalled in the Republican-controlled Senate, part of the biggest stalemate over a new round of aid for people and businesses devastated by the economic impact of the pandemic.

“Election officials needed that money yesterday,” said Justin Levitt, associate dean of the Loyola Law School who worked on the enforcement of voting rights at the Justice Department during the Obama administration. Given the trillions that Congress is spending to shore up the economy and public institutions, it is puzzling that lawmakers are resisting the few billions needed to make elections work, he said.

Voting by mail works smoothly in states, mainly in the West, which have had years to refine their procedures. But in places that are now trying to improvise in a hurry, the problems were cleared up during the primaries this spring and summer. Administrative dysfunction and fighting over voting rules left tens of thousands, predominantly colored voters, deprived of their rights as voting systems buckled under stress.

“I am afraid we are preparing for disaster unless there is congressional intervention and states get the resources they need to do it right,” said Kristen Clarke, chair of the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights under the law.

“We saw long lines in cities across the country in primaries. Those lines could be 10 times longer in some communities. “

In states where voting went wrong during the primaries, black communities tended to suffer the most.

In Wisconsin, for example, the overwhelming white city of Madison managed to open 66 voting centers. Milwaukee, more than twice the size and 40% black, had just five open sites.

Although the number of voters increased overall in Wisconsin compared to previous primaries, the state failed to mail ballots to many voters on time, and officials acknowledge that the delays deprived thousands of people.

The pandemic may be amplifying the barriers to voting that legislators had previously established. These barriers, which include requirements in some states that absentee ballots have witness signatures, that voters include a copy of their identification with their ballot by mail and that no one other than the voter can deliver their ballot to a polling place , tend to have a disproportionate impact on the suppression of the black vote.

“The primary demonstrated tremendous damage to communities of color,” he said. Michael Zubrensky, lead attorney for government affairs at the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

Georgia, which has frequently struggled with its elections, once again had some of the nation’s worst failures during the primary season. The malfunctioning of the voting machines, lack of preparedness for increased absentee ballots, and the closing of polling places contributed to the chaos in the June 9 state primaries.

Some voters waited in line for seven hours. Hundreds of thousands of absentee ballots were not delivered on time. In Georgia, as in other states, the fact that black and Latino communities have been especially affected by the virus made poll staff in cities a much bigger challenge.

In other states that are not used to voting by mail, the problems have not been primarily with voting, but with counting.

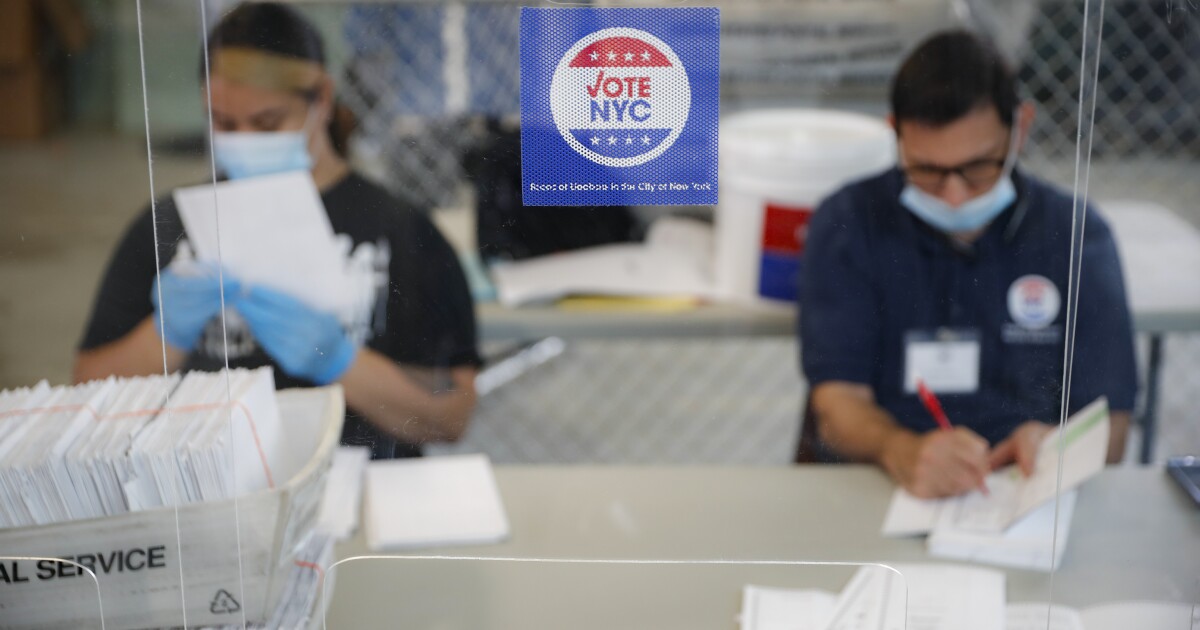

In New York, for example, results in several congressional primaries have been delayed for weeks as election officials struggle to handle an unprecedented flood of mail ballots.

Many electoral experts fear that if the November elections end close, a slow count will fuel the conspiracy theories and Trump’s efforts to delegitimize the outcome if he loses.

Additionally, a lack of voter education on how to complete and mail ballots in absentia – state-wide rules – puts many inexperienced voters at risk of not counting their ballots. In some states, the rate of rejected ballots has skyrocketed.

As election officials absorb the harsh lessons from the primaries, legal battles over voting rules that are spreading across the county have further complicated the situation.

166 cases have already been filed across the country, according to a count Levitt maintains. Many of them are disputes between Democrats who believe it is in their best interest to make voting as easy as possible and that Republicans who argue that the pandemic is not an adequate cause to relax what they see as anti-fraud measures.

The resulting court rulings are hitting the besieged election offices.

In Virginia, for example, a consent decree for the primaries exempted the requirement that absentee voters obtain a witness to sign their ballots. But the requirement is back for the general election, for now. The fight in court continues.

“We don’t know how that will turn out,” said Brenda Cabrera, director of elections for the city of Fairfax. “If we start printing ballots and the rule changes, we have a problem.”

During local elections in May, when witnesses were required, some voters who lived alone went to their office in desperation to vote.

“They had no one else to be their witness,” said Cabrera. “We went out with masks and gloves and we did it.”

The rush of dollars that supporters of both parties are investing in fights over electoral rules is often due to the belief that the outcome could help one party over another. However, in the midst of the pandemic, those calculations are often not working.

Trump’s crusade against voting by mail, for example, appears to be counterproductive in some key places.

In Florida, Republicans long held an advantage in absentee voting that has now faded as party voters heed the president’s advice not to trust mail-in voting.

Enthusiasm for voting by mail is fading fast among Republicans in other states, too, according to Charles Stewart III, an electoral management expert at MIT.

“Trump’s statements seem puzzling to me,” said Richard L. Hasen, an electoral law scholar at UC Irvine. “They can make it difficult for their followers to vote.”

All the confusion alarms Levitt. He compares the US election to a durable water balloon, with lawmakers and lawyers pushing water in one direction or another as the rules constantly change. But the strain of the pandemic, he warned, has left the globe extremely fragile.

“If you keep pressing that balloon too hard, it breaks,” he said. “And it breaks for everyone.”