[ad_1]

On Thursday, NRK was able to reveal that Forlaget Oktober is breaking its collaboration with author Per Marius Weidner-Olsen. The reason is that the publisher was unaware that the author was sentenced to prison in 2003 for “having obtained sexual relations through abuse of office or a relationship of trust,” according to the sentence.

In July, the publisher published Weidner-Olsen’s critically acclaimed novel “I Grew Up Almost Like Me,” in which the author describes raising a child who, among other things, is subjected to sexual abuse.

– This novel is not about the relationship for which you have been convicted, but rather has an overlapping theme that allows you to read it in a completely different light. It’s clearly relevant information for us, says Editorial Director Ingeri Engelstad at Forlaget Oktober. She describes this as a serious breach of trust.

– Affects the relevance of literature

One of those who gave overwhelming criticism of Weidner-Olsen’s debut novel is Dagbladet critic Marius Wulfsberg. You think the publisher is a coward who ends the collaboration with the author.

– This is a weakening of freedom of expression. If it is the case that authors cannot write about subjects for which they have been condemned, then we are in a whole new place. If this becomes a precedent, it will weaken the relevance of literature in society, Wulfsberg tells NRK.

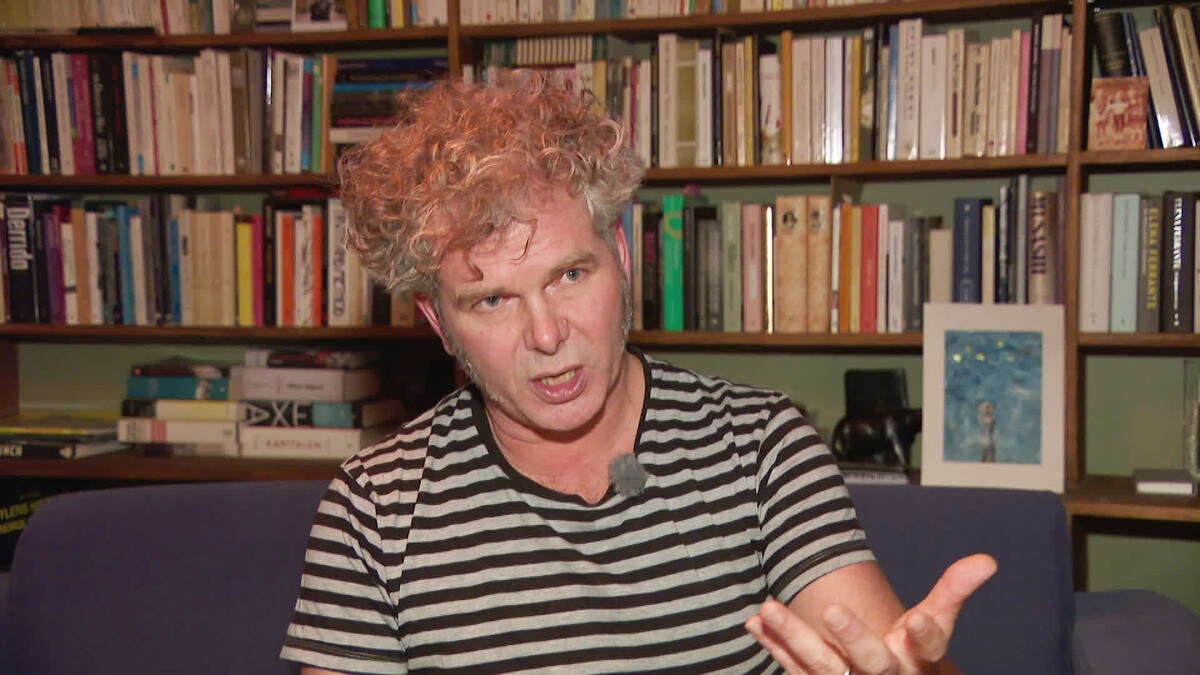

Author Per Marius Weidner-Olsen believes it was irrelevant to inform the publisher of the 17-year verdict against him.

Photo: Baard Henriksen / Forlaget Oktober

He emphasizes that literature is not a morally impeccable place, and that it cannot be the case that it should be free of convicts.

– They are complex things and literature is a place to write, reflect and try to understand the most difficult experiences of our life. Fiction is one of the few places you can do it without having to answer for everything you write, he says.

– The sentence sentenced does not prohibit writing

Kari Marstein, editor-in-chief of Norwegian fiction at Gyldendal, believes the case is demanding.

Editor-in-chief Kari Marstein at Gyldendal says she understands the case is demanding for Forlaget Oktober.

– First I must say that I do not know the case in all the details, but I understand that this has been demanding for the publisher. Good author-editor collaboration is built on trust and works both ways, he says.

At the same time, he points out that a publisher assumes a great legal and ethical obligation when publishing a book.

– Here it seems that there has been information about events from the past that undoubtedly would have been an advantage to know during the edition and not least at the launch of the book. At the same time, the protection of the author and the publication are also important. A sentenced sentence does not prohibit writing, says the editor-in-chief.

Author Tom Egeland picks up on Marstein’s point.

– Of course, there is no professional ban on convicted writers in Norway. There are many examples from the history of literature, also in Norway, of authors writing books during and after imprisonment. It will not normally be problematic for the editor, says Egeland.

He also emphasizes that he does not know all the details of the case, but states that “firing” an author is very unusual.

– May cause unpleasant side effects

Leader Heidi Marie Kriznik of the Norwegian Writers Association says it should not be the case that all authors should feel they have a duty to provide information to the editor.

Heidi Marie Kriznik, who heads the Norwegian Writers Association, believes that authors should not feel obliged to provide information.

Photo: Espen Tollefsen

– Especially about things that are so far back in time. This can contribute to an unpleasant domino effect and limited leeway for the author. But with that said, it is not the case here that Forlaget Oktober demands a certificate of good conduct, says Kriznik.

At the same time, Kriznik understands the editor’s concerns.

– It depends on the existence of a relationship of trust between the author and the publisher. I can understand that the publisher feels that he would have liked to know this, as there is an overlapping theme between the verdict against the author and the content of the novel.

She says that they have not been involved in this case and that she only knows about the case through the media.

The Oktober publisher does not want to print any more editions of Per Marius Weidner-Olsen’s novel. Kriznik notes that the Standard Contract provides support to both publishers and authors in deciding this:

“If there have been changes in conditions in the artistic, political or other areas since the publication of the work that must be assumed with certainty that they have dissuaded the author or publisher from publishing the work in its present form, each of them may require that the work not be published in a new edition or edition, or that the work not be used in other ways covered by the normal contract. The claim can be required in writing. “

Eystein Hanssen, leader of the newly created Association of Authors, says they have been in contact with the author Per Marius Weidner-Olsen:

– We had conversations with the author a few weeks ago and gave him some advice based on the information we received. What this tip was about is confidential information. But what I can say is that this is a challenging case for both the author and the publisher, he tells NRK.

Another, who is in awe of Forlaget Oktober’s handling, is the former leader of the Norwegian Writers Association, Sigmund Løvåsen. He does not want to elaborate on his views on NRK.

– Irrelevant

The publisher learned of the author’s background because the offended party in the 2003 trial reacted to the novel. The author himself chose to stand out when NRK spoke about the case. He says he did it because he believes that the editor’s handling is fundamental and ethically wrong, and because he needs to tell what the novel is about and not what it is about.

Per Marius Weidner-Olsen believes it was irrelevant to inform the editor of the verdict.

– If I had informed the editor about the verdict, it would have brought people who are not mentioned in the novel, presumably still attracted. Ethical compensation weighed more for me than consideration of the publisher’s need or right to information. In any case, I thought the information here was irrelevant, since the novel does not address the verdict, the actors, or the events in the verdict, Weidner-Olsen says.

This novel seemed to be the beginning of a stellar career for the debut author. Now the editor breaks collaboration with him.

Photo: Ola Hana / NRK

Ingri Engelstad, Head of Publications at Forlaget Oktober, answers questions from NRK:

– Could this contribute to restricting the author’s freedom of expression?

– No, this is not a question of freedom of expression. It’s about publishing ethics. When there is an overlap between the subject of the novel and the circumstances for which the author has been convicted, it is important and relevant information for us, and absolutely necessary to be able to make the ethical evaluations that we, as a responsible editor, must be able to do. . We always defend freedom of expression. But freedom also comes with responsibility. Transparency is necessary so that the editor can do a good job with the authors. Therefore, industry players agree that there is a mutual duty to provide information. It is not a question of censorship, but of the relationship of trust that must exist between author and publisher.

– Will you ask the authors for a certificate of good conduct in the future?

– No, of course we won’t ask.

– Are you going to change the practice of checking the background of the authors with whom you want to collaborate?

– No, we won’t do that.

– Dagbladet book critic Marius Wulfsberg says cowards break up the collaboration. What is your comment on this?

– You are free to think that.

– Can the author take the book to another publisher?

– Yes, you can, if you want.