[ad_1]

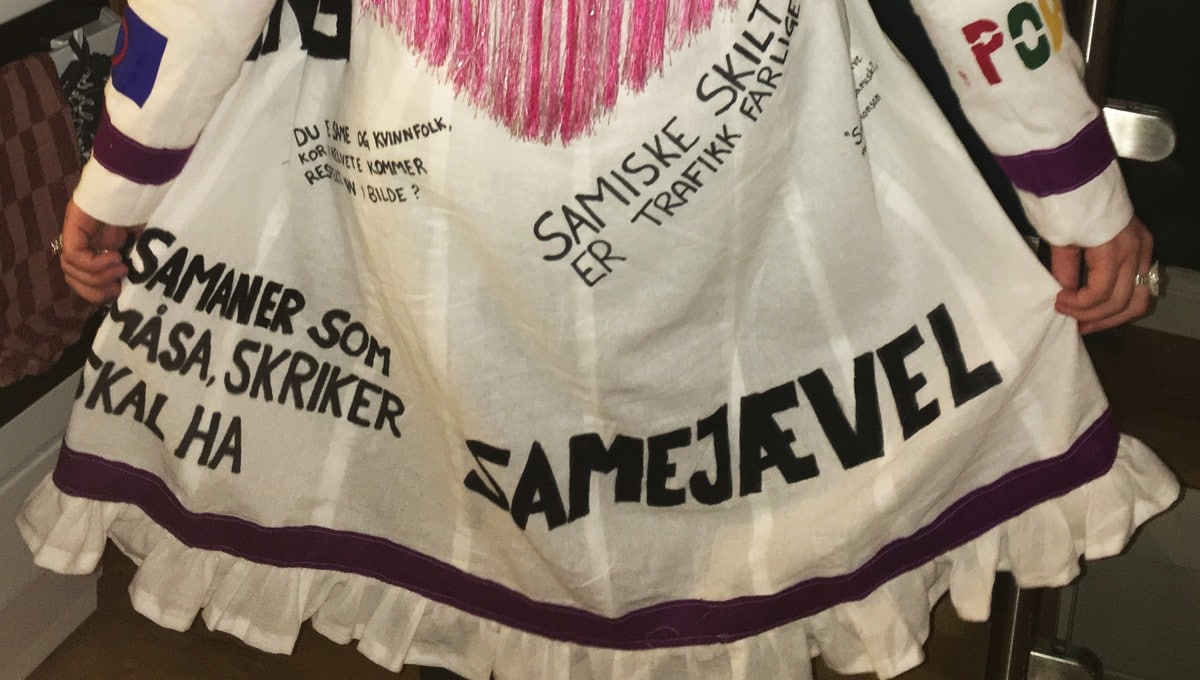

After 20-year-old Ann-Marie Dorph was harassed by an elderly woman because she spoke Sami on the bus in Tromsø, several have argued that there is a culture in the city in which Sami are harassed and harassed.

On social media, the # doarváidál or #noknu campaign is taking off and several organizations have signed the petition against the unit in Tromsø.

But Saminess is not something new, so why is this happening now and why is it happening in Tromsø?

1. Is it a single case?

Torjer Andreas Olsen, a professor of indigenous studies at the University of Tromsø (UiT), says the individual case of the bus in Tromsø has shed light on a major problem.

– There are always stories of small and large incidents of people being harassed because they go out with a cardigan or speak Sami. There are so many cases that it’s not just about individual stories, it’s systematic, Olsen says.

2. Why Tromsø?

Tromsø is the Norwegian city with the most Sami inhabitants. However, several Sami believe that they experience more Sami in the largest city in northern Norway than anywhere else. Olsen doesn’t think it’s surprising.

– Many here remember Norwegianization and it has created bad feelings and shame. For many, it is difficult to relate to their own identity and that the Sami presence is so great.

– Therefore, there will be more agitation and aggression here than in other places, says Olsen.

At the same time, he notes that it is a bit more complicated. Tromsø is perhaps the “best” and the “worst” place for many Sami at the same time.

– Many people choose to move to Tromsø because the city has a wide and diverse Sami environment. There are many here to share experiences with, says Olsen.

GREATER PRESENCE: Although the Sami are more visible in public now, it’s still rare, says Torjer Andreas Olsen, a professor at the Center for Sami Studies at UiT.

Photo: Vilma Taubo / NRK

3. Why is an agreement reached now?

Several young Sami people tell NRK that they have gotten used to Sami. After the incident on the bus, it may appear that the cup is simply clean.

– I think we’ve had enough, Ann-Marie Dorph told NRK earlier this week.

At the same time, there is a lot of discussion about how indigenous peoples and minorities should be portrayed and talked about, says UiT researcher Torjer Andreas Olsen. Like the debate on joika balls, the Diplom-Is ‘Eskimonika’ logo and the use of ‘blackface’.

I HAVE ENOUGH: Ann-Marie Dorph says she has experienced agitation several times and no longer feels sorry for it.

Photo: Marita Andersen / NRK

4. Aren’t we done with this?

RECESSED FRONT: In 2011, the Sami Association of Tromsø received this letter.

Almost ten years ago, an agreement was also reached with Sami in Tromsø. The decision of the City Council to withdraw the application to join the Sami language area generated hatred and division among the population.

Then-Mayor Jens Johan Hjort (H) later regretted the decision and said that they were destroying Tromsø’s reputation as a Sami city.

– I was hoping that the settlement we had, which was deep and brutal, would clean the air, Hjort says today.

However, the results of a survey carried out earlier this year show that one in three Sami has suffered discrimination in the past two years. It also shows that this happens in all the municipalities of Troms and Finnmark.

RECONCILED: Former Mayor Jens Johan Hjort has spent much of his political time reconciling with the Sami communities. – We should be proud of our indigenous peoples, says Hjort.

Photo: Eskil Mehren / NRK

5. Why so much excitement at the same time that the Sami have become “popular”?

– I think there is a connection there, says ITU researcher Torjer Andreas Olsen.

It points to a positive trend in which more people feel it is good to be Sami. This can be seen in the fact that more people register on the electoral roll of the Sami Parliament, regain their Sami identity, put on a cardigan, mark the National Sami Day and learn the Sami language.

– The high level of activity is also fueled by the turbidity and the history we have with Norwegianisation. It brings out bad thoughts and feelings that Sami is somewhat difficult, says Olsen.

6. Why are some people so angry with the Sami?

There has been a lot of research on how pervasive unity is and how it affects provocation, but there is less research on who is inciting and why.

– Unfortunately, we know very little about that. I think it’s about the fear that the Sami have rights and that that means that the Norwegians have fewer rights, says Olsen.

Jens Johan Hjort believes that the incident on the bus supports his impression of 2011, that it is primarily a problem with the senior escort.

– I saw a clear distinction between old and young people. I think it is ignorance and that someone is against more samer.

– Unfortunately, there are also some elderly people who are descendants of Sami and who have been deprived of their culture and language. They have learned from the Norwegian authorities that we should not have a Sami culture, says Hjort.

DIFFERENT INTERESTS: Many have come out in favor of reindeer herding in places where government industrial projects threaten operations. Here from the Øyfjellet wind farm, but there is also a heated dispute on the Repparfjord in Finnmark.

Photograph: Lars-Petter Kalkenberg / NRK

7. Is it a generational change?

Olsen notes that the older generation have a more complicated Norwegian history and that many of them feel ashamed to be Sami around their bodies.

– You probably think that it is better to be Norwegian than Sami. So why should anyone get stuck being Sami, aren’t you done with that? he asks rhetorically.

There is a generational difference here, according to Olsen. There is a consensus among researchers that children and young people feel something positive about being Sami.

– I think the new generation has recovered a bit from the pain after Norwegianization. Therefore, they can have the pleasure of being Sami and experience that there are many ways to be Sami, says Olsen.

When Ella Marie Hætta Isaksen won the Stjernekamp, ”all of Norway” could see how important Sami culture is to her and to many young Sami people.

Photo: Julia Marie Naglestad / NRK

When Frost 2 was made, Sami Parliament collaborated with Disney throughout the process. Here are Sami’s reps at the Los Angeles premiere in the US.

Photo: Siv Eli Vuolab

Sami artist Fred Buljo, known to the Keiino group, believes that Sami profiles help to make young Sami proud. Here during the finale of the Eurovision Song Contest in Tel Aviv.

Photo: Terje Bendiksby / NTB scanpix

Artist Máret Ánne Sara drew a lot of attention when she hung 400 reindeer skulls outside the Storting to support her brother, who was ordered by the state to drastically reduce his herd of reindeer. The exhibition was later mounted at Documenta.

Photo: Heiko Junge / NTB

Sami Agnete Johnsen was allowed to wear the Sami flag when he participated in the Melodi Grand Prix in 2020.