Climate change involves direct consequences on water cycling through our environment. The warmer weather has more humidity, the heavier the rain storms they fill the more water than before. On the flip side, hot air can suck up more moisture from the soil through evaporation, drought deterioration. The currents of these things should obviously change. But the amount of water in the currents varies dramatically under normal conditions, and can be affected not only by the weather. It’s hard to find trends in that data.

A new study led by Evan Dathier at Dartmouth College has started group streams in the physically meaningful category to see if relevant patterns emerge once the apples are separated from the orange. That analysis reveals several currents – both at the extremes of high currents And Low flow.

Going with the flow

Many attempts have found mixed trends between streams when analyzing peak annual flow records, where records tend to go beyond continuous measurement. Attempts to find regional examples have largely relied on factionalism by arbitrary boxes or political boundaries, which have only a limited connection to the landscape.

In new research, U.S. And there are about 540 streamflow stations in Canada, all in places that have low human impact and at least 60 years of data. To group stations, they used their location, elevation, and seasonal flow patterns. These sites are clustered into 15 different groups, 12 of which attempt to analyze trends with a large number of stations.

These groups were analyzed for extreme high and low flow frequency changes on an annual and seasonal basis. Researchers have made this calculation for different species (50 percent chance per year, 20 percent chance per year, etc.) and different early years, but the results were generally consistent.

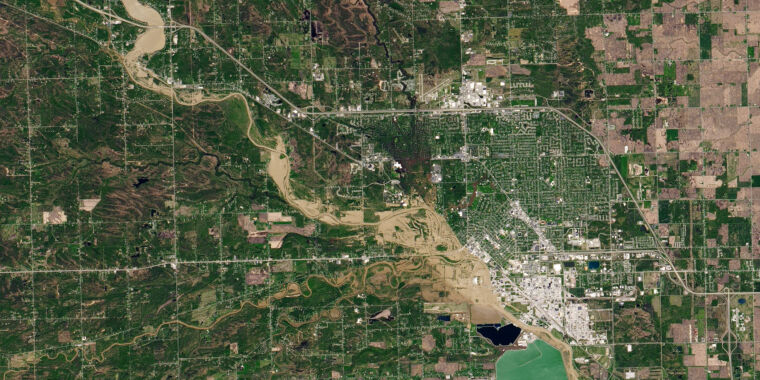

There are two broad themes that stand out from the results – one for areas where snowmelt drive peaks, and another for areas where drought prevails. Snowmelt regions include the Pacific Northwest, the Rockies (both US and Canadian parts), the Midwest, the Appalachians, and the Northeast. In these places, either in spring you tend towards peak peaks or in winter you have a peak peak flow. It is consistent with the trend towards the previous snowpack depletion with warmer spring temperatures.

Separately, stream flows in summer and autumn have become more common in the East-East, Midwest, and Appalachian regions, matching current flow trends.

Is drying

Usually in drought-prone areas-along the west coast and in the southern part of the country ના the currents look different. The increased frequency of summer and autumn low-tide events is normal, with more incidence events also being seen in the West Coast areas. Researchers point out that the low-flow events caused by drought are largely regional, which makes them stand out in the analysis. In contrast, storm-driven high-current events become more local. Still, with a large enough dataset, those trends can also become apparent.

Where regions show statistically significant trends, the researchers say, the average change a Double The frequency of such flows since 1950.

By better grouping similar currents, this method helps to strip the North American landscape of the effects of weather currents on the blue ribbons tied together. That means more actionable information on a local scale. And, researchers say, “decisions about the high and low flow events of the extreme river result in billions of dollars.”

Science Advances, 2020. DOI: 10.1126 / sciadv.aba5939 (About DOIs).