At a mostly white high school near Salt Lake City, the steps leading to the football field are covered with red handprints, arrows and drawings of Native American men in headlines meant to represent the mascot, the Braves. “Welcome to the Dark Side” and “Fight like a Brave” are next to images of teepees, a tomahawk and a dream catcher.

While lawyers have taken steps to change Native American symbols and names in sports, they said there is still work to be done at the high school level, where mascots such as Braves, Indians, Warriors, Chiefs and Redskins persist. Momentum is building under national pressure on racial justice after the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the NFL team in Washington lost the name Redskins.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE SPORTS COVERAGE AT FOXNEWS.COM

At Bountiful High School, there’s a nostalgia for the Braves name that’s been used for almost 70 years and comes with an informal mascot – a student dressed in paint. Fans point to tradition as their forearms rhythmically expand for the tomahawk kettle, wearing face paint and singing at football games.

It’s an honor, they say, but not for many Native American Americans who see the portraits in high school, collegiate, and professional sports. The images could affect the psyches of younger Indians and create the image of a non-existent monolith, lawyers say.

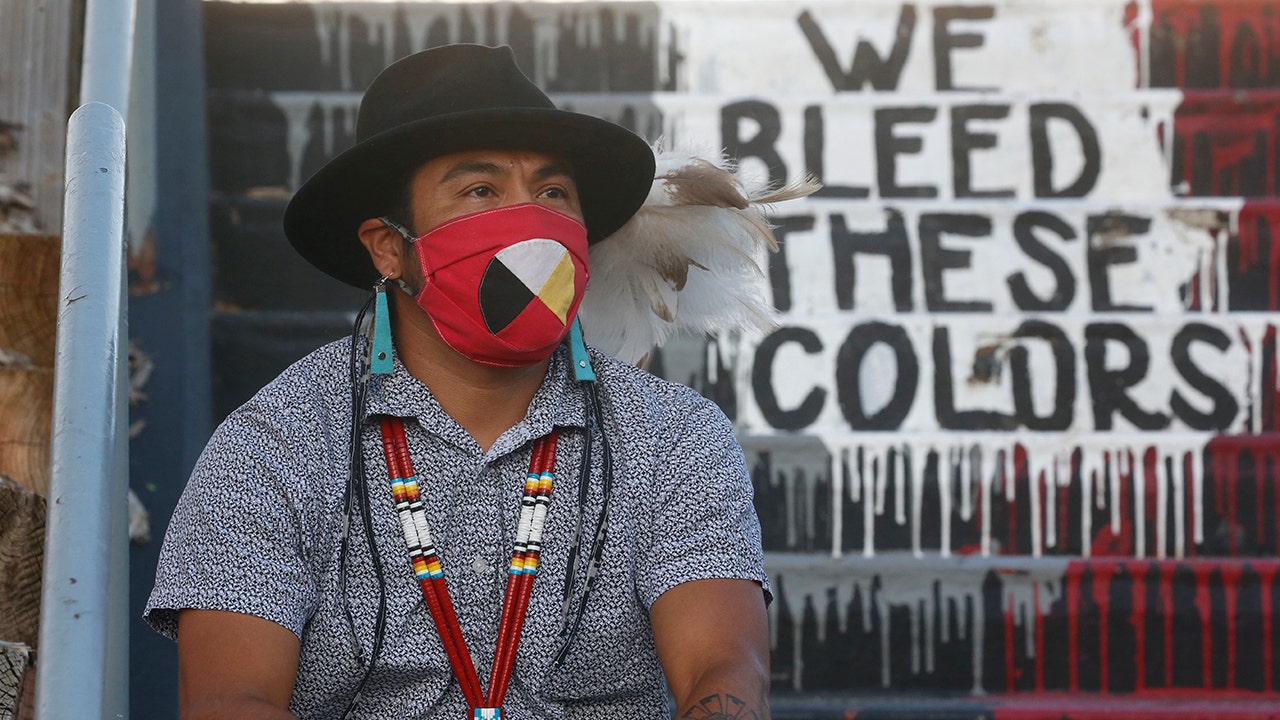

“There’s no tribe that can advertise on it,” said James Singer, co-founder of the Utah League of Native American Voters. “Despite this, many tribal governments, which exercise their tribal sovereignty, have issued statements that they do not want these types of mascots for school teams.”

It’s not clear how many high schools have built their sports team image around Native Americans, but lawyers say it’s in the hundreds – significantly down from decades ago.

Schools in Ohio, Michigan, Idaho, New York, Massachusetts and California change names, often at the urging of Native Americans. Schools in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Red Mesa on the Navajo Nation talk about their Redskins masks.

“I understand the problem, and then you have to listen at the same time to the students who are proud of this, but give them the information on why the other side is also concerned,” said Timothy Benally, who is at the Red is Mesa Unified School District Board in Arizona and is Navajo.

On a practical level, firing a mascot means new uniforms, field signs and market imagery.

Dr. Jason Black, a professor of communications studies at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte, who co-authored “Mascot Nation,” said the changes are not too expensive, but finding replacements can take time.

“You get what you pay for, and what you get is respect for people and … rebirth of a community that truly understands how to be responsible with its members,” said Black, who is not a Native American. “It’s an investment in people, and that’s who makes it.”

Only three states have laws that prohibit or restrict these symbols in public institutions. Maine lawmakers banned Native American mascots in public schools last year. In Oregon, public schools and universities may not use names, symbols, or images depicting Indians unless they have an agreement with a local federally recognized tribe. California bans “Redskins” as a team name as a mascot.

Attempts in other states to govern the use of Native American mascots have failed in recent years. At least three – Illinois, Massachusetts and Minnesota – are considering legislation this year, according to the National Conference of State Legislators.

At the university level, Native American mascots have been seen as “hostile and abusive” since 2005 banned in championships. Some schools, including the University of Utah and Florida State University, have agreements with local tribes to use their names and imagery.

Luke Duncan, an official of the Ute tribe, recently denounced the call to the University of Utah to stop using the tribe, calling the agreement a “source of pride” for tribal members.

Professional sports teams that have names and mascots with Native American themes are increasingly catching up with backlogs, including Atlanta Braves of baseball and Super Bowl champion Kansas City Chiefs. The Cleveland Indians baseball team recently said it would talk to Native Americans because it is considering a name change.

Last week, the Chicago Blackhawks said hockey fans would be banned from wearing headscarves when home games resume, but would keep their name in honor of Black Hawk, a Sac and Fox Nation leader.

At Bountiful High School in Utah, many alumni support the name Braves. Kurt Gentry, who graduated in 1976, said the mascot was treated with “enormous respect and honor and power” when he was a student.

“There is a lot of misinformation and hypersensitivity that is honestly propagated by those who have zero understanding of the culture,” Gentry said, noting that he had a Navajo foster daughter.

Lemiley Lane, who is Navajo, moved to Bountiful last year as a sophomore and said she was the only Native American student at the school. She was excited for the first meeting, but walked away when she saw the ‘Brave Man’ – a white student wearing a headband. Thereupon she skipped school clubs and sports games.

‘I could not stay there because I felt uncomfortable; I did not feel welcome, ‘said Lane. “I wanted to go home.”

The mascot is no longer allowed at school events, said Davis County School District spokesman Chris Williams. Bountiful’s logo has been changed in recent years from a Native American man to the letter “B” with a feather as an arrow on it, he said.

The fate of the Braves name and logo will not be known for the first football game this month, Williams said.

Carl Moore of Peaceful Advocates for Native Dialogue and Organizing Support said that real change will not come without the school educating students about Native American history.

“They change the logo, but it does not change the culture,” Moore said. “The culture is still racist when you go up with these steps.”