There is a huge asteroid somewhere out there Solar system, And he threw a large stone Earth.

Evidence of this mysterious space rock comes from a diamond-filled meteorite that exploded over Sudan in 2008.

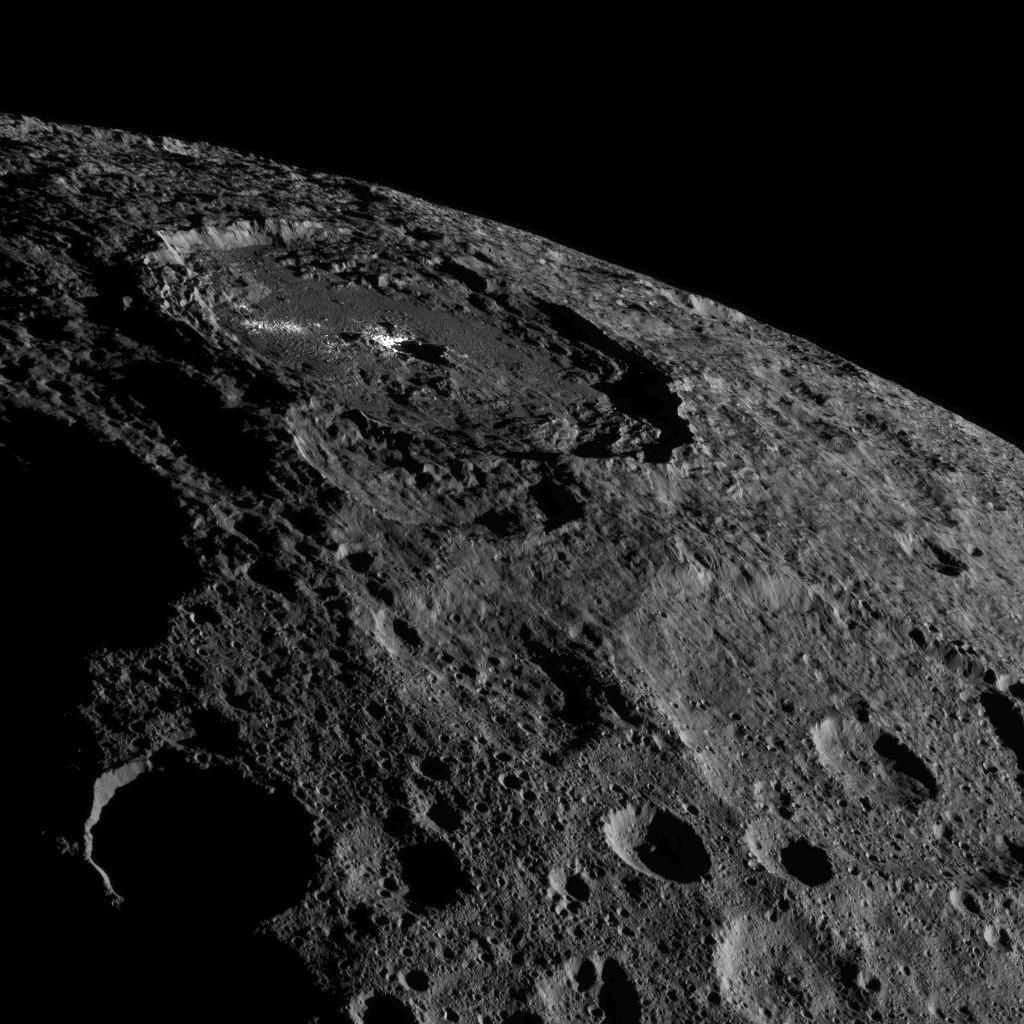

NASA’s 9 ton (8,200 kg), 13-foot (4 m) Meteor Moving towards the planet before impact, and researchers showed up to collect unusually rich fossils in the Sudanese desert. Now, a new study of one of those meteors suggests that the meteor may have shattered a giant planet – one or more sizes of the dwarf planet Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt.

Related: Reasons Reasons Astrobiologists are hoping for life on Mars

Like about 6.6% of the meteors on Earth, this one – known as Almahata Sita (AHS) – is made of a material called carbonaceous condensate. These black rocks contain organic compounds as well as various minerals and water.

This space hints at the mineral makeup “parental asteroids” of the rocks that make up a given meteorite, The researchers said in a statement.

“Some of these meteorites are dominated by minerals that provide evidence of exposure to water at low temperatures and pressures,” said Vicky Hamilton, a planetary geologist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “The formation of other meteorites points to heat in the absence of water.”

The team analyzed a Tennessee 0.0018-ounce (50 mg) sample from AHS under a microscope and found that it contained a special mineral makeup.

The meteorite uses an unusual suite of minerals that form “intermediate” temperatures and pressures (higher than what you would find in a typical asteroid, but lower than inside the planet). Amphibol, a mineral in particular, also needs prolonged exposure to water for growth.

Amphibol is common enough on Earth, but it only appeared once in a trace amount in a meteor known as Allende – the largest carbonaceous chondrite ever found, which fell in 1969 in Chihuahua, Mexico.

The amphibole content of AHS indicates that the fragment has broken the parent planet that has never before released meteors on Earth.

And samples taken from the asteroids Rayugu and Bennu, respectively, by Japan’s Hybusa 2 and NASA’s OSIRIS-Rex probes, will likely reveal more space rock minerals that rarely turn into meteors, the researchers wrote in their study.

Hamilton said some types of carbonaceous chondrites simply could not survive a dip in the atmosphere, and that prevented scientists from studying the flavors of chondrites that might be more common in space.

“We think the solar system has carbonaceous condensate content represented by our meteorite collection,” he said.

The paper was published in the December 21, journal Nature astronomy.

Published on Original Living Science.