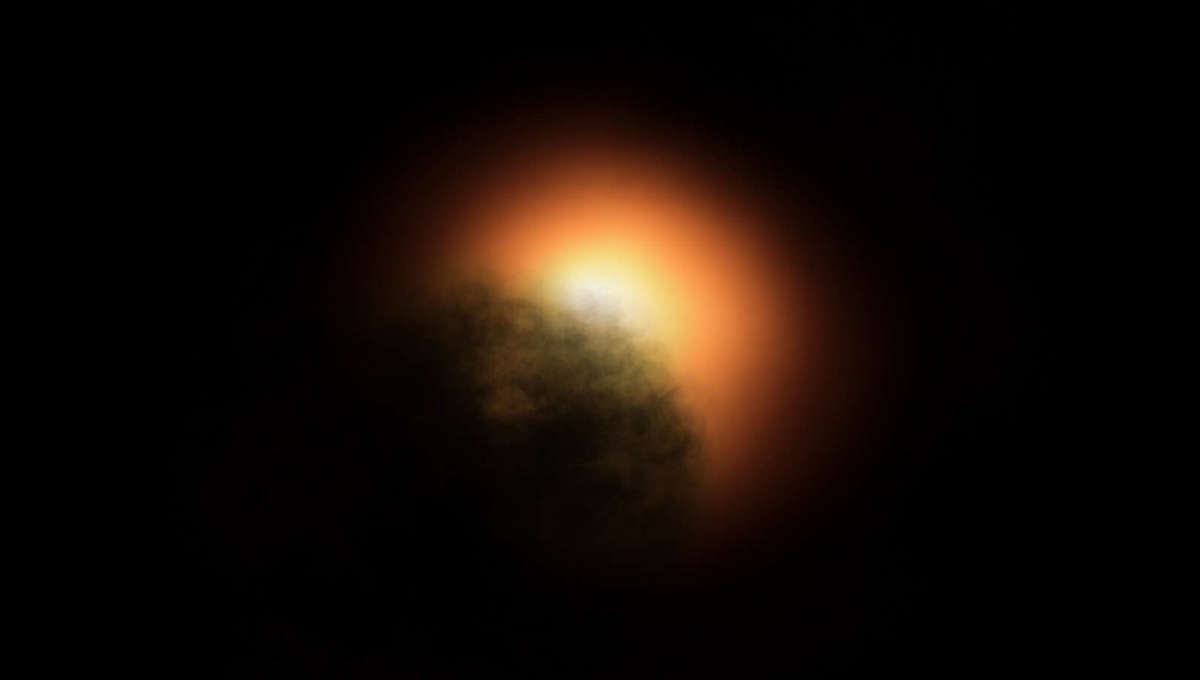

The smoking gun (in a sense, literally) may have been found for the reason why Betelgeuse, everyone’s favorite red supergiant star, evaporated so dramatically earlier this year: Dust. A lot of it.

It’s been 75 years since 2020, here’s an update: Betelgeuse is one of the brightest stars in the sky, lying in the constellation of Orion (his right armpit; the name literally means “The armpit of Orion” or “The Axis of the Giant”). It is a red supergiant, a colossal star with 15 times the mass of the sun and a diameter of half a billion kilometers or more.

It undergoes regular variations in light, brightness and dimming over time. There are a few cycles on top of each other; one lasts about 420 days (plus or minus), and the other about 2000 days. These variations usually change the brightness by a small amount; you should really pay attention to notice under normal circumstances.

But in late 2019, Betelgeuse took a nosedive, and by mid-February 2020, its brightness had dropped by a whopping 70%, so of course you could just go outside and see it.

Astronomers knew this did not mean that an explosion was difficult – a supernova is when the star’s core collapses, but Betelgeuse is so swollen enormous that its core and outer atmosphere are essentially independent of each other – although of course speculation online ran rampant. But still, this was a big mystery. What could cause such a large drop in brightness?

Betelgeuse is so large that observations show it as a disk, and by early 2020, the southern half of the star could be seen physically dimmer! One idea is that an enormous starspot covered its surface. Like sunspots, these are shorter, darker streaks on a star, and it is known that red supergiants are plagued by them. Some of the evidence supports this idea, others do not.

Another idea is that Betelgeuse blew an enormous cloud of dust. Red supergiants do this too. Stars like this physically pulsate, with their upper layers expanding and shrinking by large amounts (this is what causes the period of 420 days; if the star is larger, it emits more light, and when it is smaller, it emits less) .

So what is it? The mystery now looks almost definitively solved: New Hubble observations of the inflated supergiant show strong evidence that the southern hemisphere underwent significant illumination in the ultraviolet right before the sudden dimming event. This is what you expect from a pulse moving upwards through the star, the same kind of thing that generates the enormous dust eruptions.

The observations used the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (yay, STIS!), Which can look at the ultraviolet. It takes spectra, where light is refracted in its constituent colors, hundreds or even thousands of them. This isolates the signatures of various elements in the atmosphere of the star that give diagnostics of the conditions there.

STIS observed Betelgeuse in January and March of 2019, which was in the star’s normal behavior, then again several times in late 2019 and early 2020, during what was called The Great Dimming. Betelgeuse is so large that the camera could look just to the southern hemisphere, where the dimming happened later, and that is where they found the UV shenanigans.

The STIS observations also indicate an increase in the density of the gas in the upper atmosphere of the star at the same time as the UV glare. What it saw was that gas was getting hotter and denser: just what you would expect from a pulsation wave through it.

The authors speculate that convection – hot gas rising in the star’s atmosphere – may have triggered a more significant upward flow (a plume), and this coincided with the normal extension of the periodic cycle of Betelgeuse. This caused a massive pulse in the atmosphere, heating and compressing as it rose. Once it reached the very upper limits of the star’s surface (as it is; the star is so inflated that it just slowly disappears as you walk out without an actual surface), the gas was cooled, dust formed, opaque, and blocked the light coming from the star beneath it.

Dust in space comes in two types; silicaceous (rocky) grains, and grains of complex carbon chain called – get this – polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. That is soot in principle. If this was made in the atmosphere of Betelgeuse and helps to cause the dimming, then it is literally like smoke, hence the expression smoke gun. On the other hand, some work indicates that the made grains were larger than normal, which would mean they were silicates, and my ordnance-based metaphorical expression falls short. Except it was a pellet gun. Hmmm.

However, this all seems to add to Betelgeuse sneezing / belching / flattening of a huge cloud of dust, large enough and dense enough to block most of the star’s light. Again, seeing that Betelgeuse is a billion miles wide, that’s an enormous load of dust.

Can this happen again? It does not seem likely, because such a deep dip in the light has never been seen before (large drops have been seen, just none like this). However, some observations have shown that it can dim again! Maybe there was another dust eruption, smaller this time. Unfortunately, this happened while Betelgeuse was too close to the sun in the sky to observe from Earth (the dimming was seen by observers of suns that are currently in another part of the Earth’s orbit, with a very other view).

We may know better soon enough; Orion starts just early in the morning enough to get sightings again. Stay tuned! The armpit of Orion is perhaps just at the beginning.

.