By John Miller

ZURICH (Reuters) – Many studies evaluating the accuracy of antibody tests against COVID-19 had major shortcomings, a review published Thursday concluded, offering more evidence that blood tests are of little use to people seeking know for sure if they have been infected.

Cochrane, a British journal that reviews research evidence to help decision-makers adopt better health policies, analyzed 54 studies, mainly from Asia, that sought to measure the reliability of tests that purported to show whether someone had developed antibodies against the new coronavirus.

The studies were often small, did not use the most reliable methods, and the results were often incomplete, Cochrane said in its 310-page report.

Furthermore, most of the examinees had been admitted to the hospital, without giving an idea of how well the tests could detect antibodies in most people with milder symptoms.

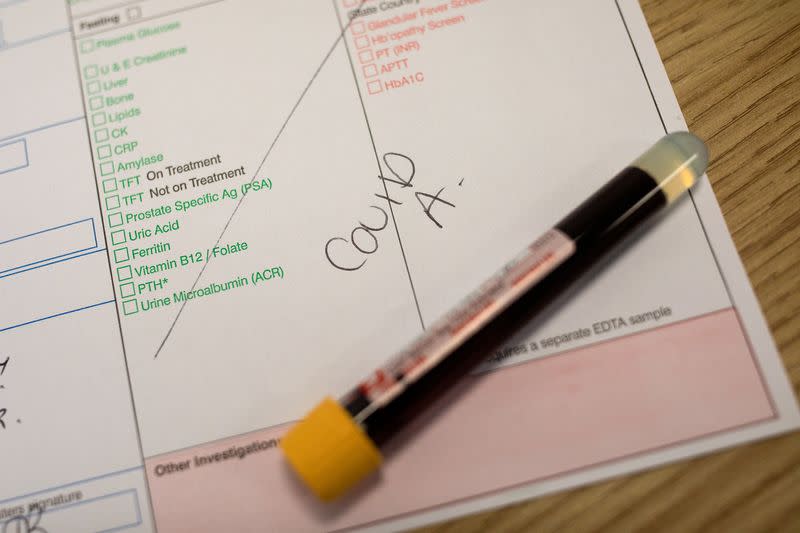

There is great interest in these antibody tests, which are based on a finger prick or a venous blood draw, by people eager to know whether they have had COVID-19 or not.

It has been speculated that a positive result could mean that people have some protection, at least temporarily, from reinfection. Such hopes are unrealistic, said Jon Deeks, a professor of biostatistics at the University of Birmingham who leads Cochrane’s evidence assessment efforts.

“A lot of people in the UK are very interested and eager to know, but there is no decision they should make at this time based on the results of that test,” Deeks told reporters.

In total, the Cochrane researchers identified data from 25 commercial COVID-19 tests, a fraction of about 300 of those tests that exist. Its review did not include tests offered by Roche or Abbott Laboratories, which were approved by regulators after the April 27 deadline.

Updates to the Cochrane report plan to include test data from both companies, which now sell for millions in the United States and Europe.

While the Cochrane-reviewed studies showed that antibody tests were better at detecting COVID-19 antibodies in people two or more weeks after symptoms started, they did not provide clues as to how well they work in patients further from the infection.

Such gaps undermine the value of testing as tools in so-called “seroprevalence studies,” to determine what percentage of people in a population may have been exposed to the virus.

“We don’t know how well these tests work after five weeks, so that’s our biggest concern,” said Deeks. “In seroprevalence studies, you’re looking beyond that and we really need some data that says, ‘How well do they work at three months, four months, five months?

UNDER SCRUTINY

The veracity of scientific studies has come under scrutiny during the pandemic, even more so after the British medical journal The Lancet issued an apology after publishing a study on the health risks of the anti-malaria drug hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID- 19 which was withdrawn by three of its authors.

Cochrane said that of the 54 studies it analyzed that covered nearly 16,000 samples, 89% were at high risk of bias based on how participants were selected, as they were unlikely to match patient populations in clinical practice.

Cochrane said there were more problems, which often did not mention whether the samples were anonymized or blinded, which could lead technicians to repeat the tests if they thought they had obtained an incorrect result.

Some studies retained the results, while others included five or more samples per patient, resulting in inflated sample sizes and results that were falsely accurate, Deeks said.

“For many of the studies, we were never able to find out how many patients were included in them,” he said. “All we know is how many samples were analyzed.”

(Report by John Miller, Edited by Timothy Heritage)