[ad_1]

There have even been expert voices calling for COVID-19 not to be controlled but to be completely eradicated from the new coronavirus disease.

New Zealand has almost succeeded, but after 100 days with no new cases of the disease, infections from international travel and other unknown sources have returned.

And if applying all these strict measures can help tilt the infection spread curve downward, complete eradication of COVID-19 is an incomparably more difficult goal to achieve.

For some isolated island states, like New Zealand, which has shown this by example, this may be possible. Only later should care be taken to ensure that those infected do not come from foreign countries. And that would likely mean tighter and longer restrictions on international travel and testing of all international passengers before and after the trip.

Knowing that long-term border closures are difficult for the country’s population to accept, and that internal control measures alone cannot achieve a sufficient effect, it is impossible to achieve zero levels of infection. But if we use different methods, it could become an achievable goal in the future.

The best strategy is immunity.

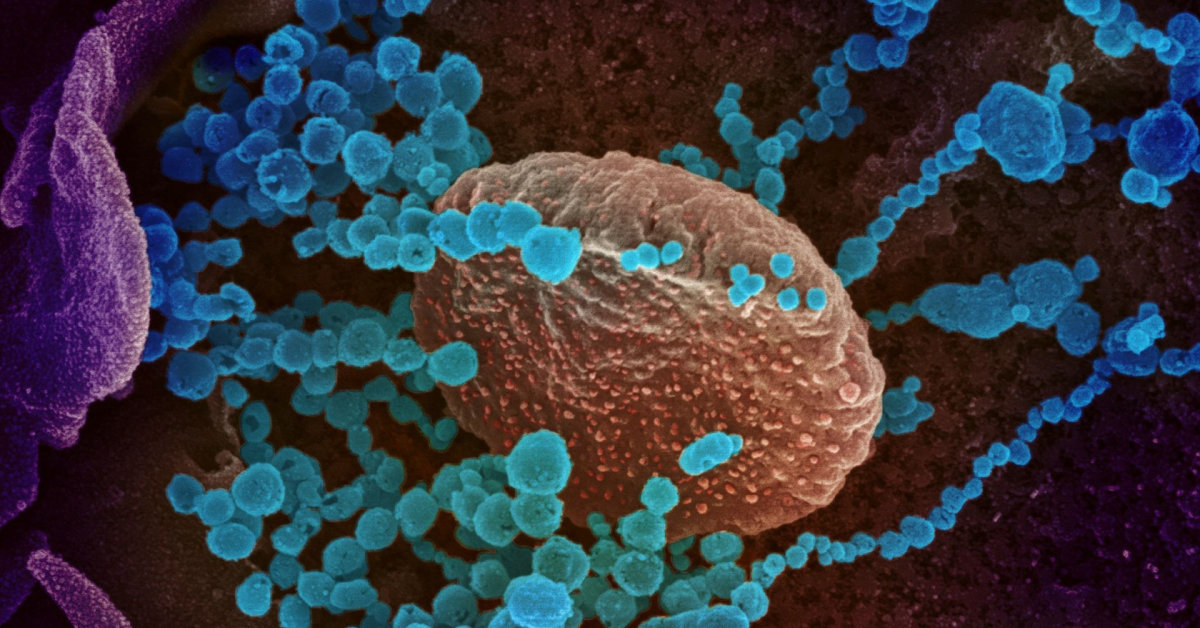

The most effective way to control COVID-19 is to use the body’s natural defenses – the immune system.

Recovery from a viral infection is generally associated with the development of specific immunity. It is not yet clear whether the recurrence of SARS-CoV-2 provides immune protection against reinfection, but there are very few cases of people becoming infected with the same disease a second time.

Most infected people develop specific antibodies against the virus. And although the formation of antibodies is not guaranteed in an asymptomatic version of the disease, that infection can still activate the T cells of the immune system, which are another line of defense for the immune system. Thus, in one way or another, the appearance of COVID-19 seems to confer immunity to this disease in most people, at least for a short period of time.

With this in mind, some researchers have proposed allowing the virus to spread in society, but protecting that part of the population that is called at risk, the elderly or people with chronic diseases. The ultimate goal of this idea is the development of so-called “herd immunity”.

Such immunity arises when a sufficient number of people appear in society to prevent the disease from spreading freely. For some highly contagious diseases, such as measles, the threshold for “herd immunity” is quite high: 90-95 percent of that population must be resistant to the spread of the disease in society. Some experts have hypothesized that in the case of SARS-CoV-2, this threshold should be significantly lower, around 50 percent, but most researchers agree that it is slightly higher, than 60 to 70 percent.

But now there are very few people who have contracted SARS-CoV-2 and have recovered. For example, an antibody test in Dublin, Ireland, found that only 3% of the population has resistance.

In New York City, USA, the figure is much higher than 23 percent. However, the fact that there are so many people with COVID-19 antibodies in New York means that many more people have died in that city, even considering that the city has a much larger population than Dublin anyway.

And in Sweden, where very liberal pandemic management measures were applied, the number of infected people was much higher. There were up to 10 times more deaths from COVID-19 in this country than in neighboring Finland and Norway, in relative terms, per million inhabitants.

Naturally, we can expect that the impact of the second wave of coronavirus in those “seriously ill” states will be less than in the rest. But if that threshold of “herd immunity” is not reached, society will still not be protected and the virus will spread.

But the inevitable consequence of naturally reaching the limit of “herd immunity” will be death. Significantly more people will die at risk: older people, overweight citizens and people with chronic diseases.

Also, some people with the disease will develop long-term health problems, sometimes even those whose illness has not been serious.

Therefore, the natural “herd immunity” development path is a completely unacceptable strategy to limit the spread of the virus, not to mention its complete elimination.

Vaccinations to help?

The goal of achieving complete eradication of COVID-19, which is theoretically difficult to achieve, can be addressed by acquiring immunity through vaccination.

For example, in many parts of the world, vaccines have helped reduce the spread of diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, measles, rubella, mumps, and Haemophilus influenzae type B.

Currently more than 200 different SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are being developed in various laboratories around the world. But even that doesn’t mean that full COVID-19 is an easy goal to achieve. This requires that the vaccine be very effective in preventing the virus from becoming infected and in preventing the virus from spreading from the person who has been vaccinated to others.

And the same cannot be said for the more advanced vaccines right now. Currently, the target for vaccines closest to certification is at least 50%. efficiency is a threshold beyond which the US Food and Drug Administration.

Of course, waiting for an incredibly effective vaccine to be developed for the first time is very optimistic. Furthermore, the vaccine should work equally well in all age groups and be safe for use in the general population. The issue of safety is very important: any safety issue will reduce confidence in the vaccine and the level of vaccination in all age groups.

Also, the vaccine will have to be produced in large quantities. After all, more than 7 billion people will need to be vaccinated, and that will take time.

For example, AstraZeneca, which has launched production lines for one of the best vaccines currently being tested, has been contracted to produce 2 billion euros. doses until the end of 2021. The world will take even longer to produce these vaccines.

And the effect would not be felt in an instant. For example, the last case of smallpox was medically recorded in 1977, a decade after the World Health Organization launched a global program to eradicate the disease and nearly 200 years after the first vaccines against the disease were developed.

Unfortunately, it took more than 30 years to eradicate polio from most of the world, with the exception of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Therefore, while a highly effective vaccine would provide us with the best chance of achieving zero levels of morbidity from COVID-19, we must realistically assess the expectations and opportunities. Eradication of the virus worldwide, while achievable, will undoubtedly take years.

[ad_2]