[ad_1]

17th century John Graunt, considered a pioneer in epidemiology, studied four decades of deaths in Britain amid the fight against outbreaks of smallpox, fever and typhoid, the Financial Times reported.

In 1666, Graunt realized that these data could serve to support a simple idea: epidemics do not end when diseases disappear, but when mortality is similar to that recorded in normal times.

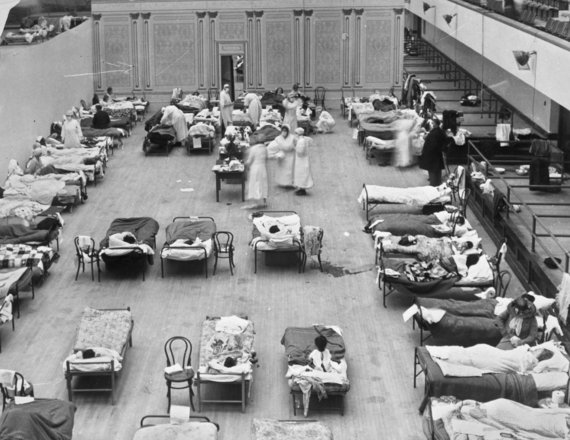

Scanpix / AP Photo / Temporary Hospital During the Spanish Flu Pandemic

400 years later, the Oxford Vaccine Principal Investigator made a similar thesis on COVID-19.

“The end of a pandemic is not the end of a virus, it is the end of an unsustainable impact on health systems. “If we can make it less harmful, we will see the end of the pandemic,” said Andrew Pollard.

With infectious strains of coronavirus emerging more rapidly earlier this year, the number of infections has increased and governments have expanded restrictions. Sometimes it starts to look like a pandemic will never end. But history shows otherwise. Pandemics end, but their end is rarely in order

Diseases rarely go away completely, and outbreaks don’t end everywhere at the same time, writes the Financial Times.

Consequences of Spanish influenza

Influenza A, whose various strains have spread around the world, is a classic example of the disease reaching epidemic levels before breaking out and then returning in unpredictable waves. The disease first appeared among humans in the 16th century.

One particularly contagious strain was the Spanish flu, the pandemic of which occurred in 1918-1920. Medical historians still debate how it ended. Some claim to have infected enough populations to develop natural immunity. Others believe that the Spanish flu has mutated less deadly over time.

However, it survived in the world until about 1922.

The first influenza A vaccine was developed in the 1950s, but the pandemic continued to slowly decline. Genetic “relatives” of the Spanish flu were responsible for the Asian flu outbreak in 1957, the Hong Kong flu epidemic in 1968, and outbreaks continued to break out later.

“If we can get to a flu-like level, where most people feel fine, when we have a coronavirus season every year, then we can deal with that,” Collard told the Financial Times.

Like influenza A, COVID-19 will probably never go away completely. And attitudes about the risks posed by the virus will change over time.

“Pandemics end when something that society considers unacceptable turns into something that can be fatal, but somewhere in the background,” said Erica Charters, associate professor of medical history at the University of Oxford.

Researchers talk about when a pandemic or epidemic becomes endemic.

Recently, researcher Kristin Heitman wrote that “this is the time when the relevance of a disease outbreak diminishes enough to draw public attention to the moral and social crises that the disease has caused or exposed.”

The exception of smallpox

Smallpox is the only pandemic that has been completely overcome. But this is an exception.

The campaign to eradicate the disease began in 1966 and ended in 1979 in Somalia.

“Smallpox teaches us that the vaccine alone does not cure the disease,” warns Alexandre White, associate professor of historical medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

akg-images / Scanpix photo / A child with depression in Colombia

The smallpox vaccine was developed in Britain in the 18th century, but Western doctors weren’t interested in passing the vaccine to distant parts of the world until increased travel increased the risk of contracting the disease again.

History shows that pandemics never end for everyone at once. Polio has not been around in Europe, North America, South America and Australia for a long time, but it is still prevalent in parts of Africa and South Asia, according to the Financial Times.

The first major polio pandemic was detected in the United States in 1894, and it peaked in 1952 when nearly 60,000 people were infected. children, thousands of them were paralyzed, another 3,000. passed away.

The polio vaccine was developed in 1955, and by 1979, the disease in the US had already been eradicated.

In the 1970s and 1970s, vaccination was taking place at a similar rate in Europe and the Soviet Union, but campaigns in the south were less effective.

Africa declared that it had eradicated polio in August, but new cases of the disease were reported in South Sudan in August.

[ad_2]