[ad_1]

Vilnius and London came together for a conversation about responsibility for the facts and the text, portraits of Peter I and Catherine turned into letters on the covers, how the author managed to create thoroughbred characters, and how writing a novel changed the author himself during the pandemic.

Challenges for you

When asked how successful he was in writing the book during the pandemic, the author made no secret that it was not easy.

“At the time of writing this latest book, the pandemic has disrupted all my limited habits and opportunities. In fact, I don’t know how I did it myself. I will not hide that it really was extremely difficult, and that is why I say that this book is bound with my gray hair. I just had to fight for every hour of free time to write, and the responsibilities and problems with the pandemic really increased. This writing journey has become obsolete for me. Time passed, a long period of time during which many things and experiences happened. And I am definitely not the same as when I started writing, “said K. Sabaliauskaitė.

According to her, one of the most important leitmotifs in the book is time, which symbolically fits into 24 hours.

“The book is written in real time. I like to throw myself various virtuoso challenges, invent all sorts of quirks to make it harder to create, and this book is no exception. Since time is a very important leitmotif in him, I thought I should try to write a book with all the flow of the subconscious, with all the real action, and put it together so that one chapter is an hour of real time. The text had to be managed responsibly, as a chapter had to fit on 24 pages of the manuscript. The number 24 became a kind of destiny; Then I realized that 24 years had passed between Martha’s relationship with Pedro I and his death, “said the author.

Responsibility for facts and text

When asked by Rytis Zemkauskas if he felt responsible for the actual authenticity of the works, the author did not question him.

“The way I work and the novels I write are historical novels and are infinitely woven. I can’t begin to move, pinch, because then the whole story will slip away like the eyes of a sock. Therefore, I take full responsibility for what the text is and what I say. After all, I am a scientist first. When writing a research paper, all the facts should be presented in a logical, methodical way, there can be no nonsense. The preparatory work, the very long studies of sources and documents from that period are always very important to me. And only after collecting it and putting it all together, do I feel next to the text as an author, as a writer, and I have empathy, “said K.Sabaliauskaitė.

Therefore, according to the writer, it is not worth looking for great similarities between her and the character in the book.

“If I wanted and could identify a lot with the main character, it would hardly be very healthy psychologically. I see the empathy and identification of the actors with them as writing rather as an actor on paper. I try to put on my hero’s coat, I try to live up to his motivations, his reactions. When it comes to identification and likeness, it seems to me the opposite: when writing, you have to get out of who you are, get out of your comfort zone and try to empathize with another, stranger, whose story you are trying to tell. ”The author is convinced.

R. Zemkauskas asked: what happens if a very good literary walk is invented, which slightly exceeds the historical truth? How does the author behave then?

“When writing a historical novel, that feeling is, in fact, the first sign that the literary procession is definitely not so good. It usually happens to me in another way: in the investigation sources arise that reveal motives, those literary movements, and dictate For example, the second part is the story of a baby rescued from the waves of the storm in a barrel of a sunken ship. And, no matter how fabulous it may seem, it is a true story described by a Scottish officer who accompanied Peter I during that campaign. And when you come across such a story, you can’t be indifferent, “said the author of” Empress Peter. “

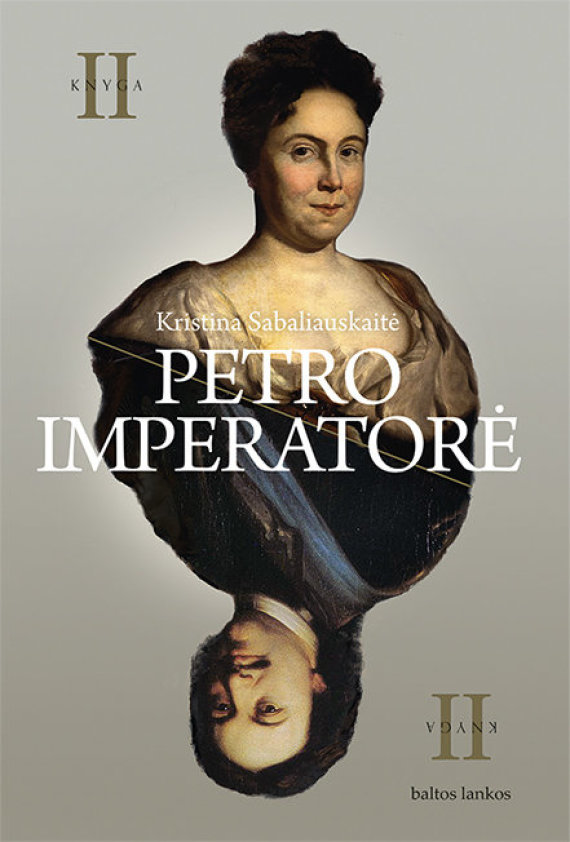

Editor’s Photo / Book Cover

Portraits turned into letters

Readers are also drawn to the covers of both books created by artist Zigmantas Butautis: they show portraits of Peter I and Catherine as if they were cards.

“Peter I and Catherine I, when she was a mature woman and became the official Tsarist, were repeatedly portrayed by very important European artists, both French and Dutch, and then by artists of the Russian school. And these two portraits are very , very important because, in my head, the work painted in 1717. In The Hague, it is the most representative of his psychological world, his personality. An unadorned, unpolished and unadorned portrait that reflects how he could have really looked. It is very interesting that Peter I recognized himself in his portrait: it is documented that looking at this portrait he said that “here I really am sharia“- this is exactly the word he uses, but he did not like the portrait of Catherine at all.

And you can understand why. After all, the painting greatly exposes her soul, it is clear that she is a strong woman, full of her sense of value, of a certain dominance. He left the portrait in The Hague with the Russian envoy Kurakin and did not take it to St. Petersburg. And this portrait entered the Hermitage only in the 19th century. pab. ar XX a. At the beginning, from the Kurakin family kits. And it seemed to me that it was this portrait that would be on the cover of the book ”, said K. Sabaliauskaitė

And is the fact that the cards are turned in the second part a completely conscious decision?

“Yes, because the cards are turning. At the end of the life of Pedro I, it was Catherine who took the lead in his history. And the title of the book is very ambiguous – understand it however you want. Does “Empress of Peter” mean that she was the Empress created by Peter, or still the Empress who ruled Peter? I think that, as in any relationship or marriage, the situation can be interpreted this way and that way ”, explained the writer.

What is that Russia like?

According to the author, the first book showed that our knowledge of Russian art, literature and culture ends in the Soviet school, and if someone is still interested, it is more by inertia, an old groove.

“After all, it doesn’t work in the Lithuanian cultural circulation, because the most important books on Peter I, which are really well known to Western European readers, are simply not translated. Although Orlando Figes work on the cultural history of Russia, we have not done so far. We are not familiar with the work of British historians, Yale professors, and finally Russian scientists themselves on this subject. There is still an extremely interesting work by Marquis Astolpheʼ de Custineʼ “Letters from Russia” – we don’t have it in Lithuanian either. This is his 1839 travel journal. Lithuania and Poland are also mentioned a lot in the book, because the action described in the letters takes place after the 1831. uprising. There is simply no in-depth approach, especially for Russian superior literature or more serious historiography. And, in my head, a lot is missing. For example, what are we currently translating from major high-caliber Russian authors? ”Asks K. Sabaliauskaitė rhetorically.

The second part of the book is a quote: “In Russia, God is not love, but fear.” What does that mean?

“I have the impression that this is probably one of the biggest and most surprising differences between Western Christianity and the Eastern Orthodox tradition. After all, the image is sometimes more eloquent than many words, and this difference we will see clearly when we look at the icons of the Eastern tradition and the images of Christ painted in the West. In the East, it is obvious that Jesus is not a handsome young Jew with a beard and eyes full of compassion, pity and love. No, it is a very gloomy image with a large worry wrinkle on your forehead. The iconic oriental image of Christ is impressive and disturbing, very intense, just omnipresent. It seems to me that the visualization is very different and very eloquent ”, says the author.

Although in the last decade, after the “Silva rerum” tetralogy, Lithuania has seen an influx of historical novels, according to the author, we are still not characterized by a linear historical narrative: “As a culture, we are not followed by others. We really lack this perception, such self-awareness, and it probably won’t give us long-term projects that have a vision for the future that we probably don’t already have. Education, parks, gardens, museums, monuments. I would say that we are characterized by peasant thinking, which also comes from the image of Lithuanian literature: a cycle of years, from harvest to harvest. Even current semantics, when it comes to literature in Lithuania, is related to this kind of thinking, not to the historical linear narrative. Therefore, history as a line, as an epic, does not have a very deep tradition in our culture ”.

[ad_2]