[ad_1]

The causative agent of the flu has been sought before, but was thought to be a bacterium. 1892 Bacteriologist Richard Pfeiffer (1858–1945) reported discovering the causative agent, the Haemophilus influenzae bacteria, which was later named the Pfeifer (bacillus) bacteria.

1918-1920 During the pandemic, it was understood that it was not the Pfeifer bacteria that caused the flu, but rather something else.

For researchers to say I would say that the Spanish flu pathogen had been discovered, known and restored, 87 years should have passed since the pandemic began.

Numerous scientists contributed to the discovery. Not only virologists, but also developers of modern technologies, scientists in molecular biology, genetics, and other fields.

Research in Alaska in 1951

The influenza virus was first isolated in the 1930s from pigs, and in 1933. – from a person with the flu. Therefore, effective virological investigations of influenza were initiated.

Every year different types of viruses cause the flu, but humanity and scientists couldn’t forget the deadliest from 1918-1920. Spanish flu.

Scientists were increasingly concerned with the origins of the Spanish flu, what caused it, and how to protect against it. The pandemic could have recurred. The need to know, research and develop measures to prevent the Spanish flu has been understood.

Johann Hultin (b. 1925), a graduate of Uppsala University, came to the University of Iowa (USA) in 1949. and began his master’s studies here, and then his doctorate studies in microbiology.

The choice of the subject for the doctoral thesis was determined by the 1950s. Academic discussion on the Spanish influenza pandemic and dr. The words of William Hale (1898–1976) say: “Someone should go north and find the eternal frost of 1918. agent of the flu.”

This idea determined the choice of research topic for 25-year-old doctoral student J. Hultin. He speculated that Alaska might be the most appropriate site for such an archaeological study.

After receiving approval from the university, he began planning an expedition. After coordinating the topic of the work, he received valuable advice from the paleopathologist Otto Geist (1888–1962), as well as 10,000. research dollars, 1951. In May, Hultin flew west of the Sioard Peninsula in Alaska.

According to the writing exactly 1918-1920. selected three sites for archaeological research on the Siouard peninsula for epidemiological data. The flu victims’ cemetery in the small town of Brevig Mission was the most suitable place to investigate.

Johan Hultin (left) and colleagues at the University of Iowa unearth the grave of those who died of the Spanish flu. Brevig Mission, Alaska, 1951

During the pandemic, 80 adults lived here, mostly Inuit (a branch of the Eskimo ethnic group). Infected with the influenza virus in a few days, in 1918. November 15-20, 72 of them died. Only 8 adults and some children remained. Almost the entire rural community was buried in a grave.

The way the flu virus has reached the periphery of the world is told in several ways. Some say that the traffickers came with the dog sled, others say that the postman has spread the pathogen.

Three in 1918. Villagers who survived the pandemic in 1918 were able to tell the incredible events of November.

Hultin gained the trust of the community, was able to adequately explain the importance of his investigation, and received permission from the village elder to dig a cemetery and exhume the bodies. He called several colleagues from the University of Iowa for help.

While burning bonfires, they thawed the ground so they could dig a grave. The bodies were buried at a depth of 2 meters and perfectly preserved. The girl’s body was first exhumed and part of her lung tissue was removed, followed by a few more bodies.

The researchers knew they were looking for a virus that would kill millions of lives, but they used only the simplest means of protection: surgical masks, rubber gloves, and autopsy tools sterilized in boiling water.

The samples had to be kept frozen, so Mr. Hultin returned to the university laboratory as soon as possible to begin the study. The ice ready for freezing melted quickly, and the Alaska to Iowa trip was a long one.

The plane landed multiple times to replenish fuel supplies, and Mr. Hultin attempted to cool the samples with carbon dioxide gas from the extinguisher at each stop.

Upon his return to Iowa, investigations began urgently, lasting a month and a half. He injected samples of lung tissue and extracts into fertilized chicken eggs, hoping to multiply influenza viruses.

There were also attempts to infect five test ferrets with the virus through the nasopharynx, with no symptoms of the disease. From the collected material grew Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria

Various investigative methods were used until material shipped from Alaska was finally depleted. Failed to save virus. At an unprecedented rate during the pandemic, a human-to-human virus died during the journey.

Search in Norway, beyond the Arctic Circle

It was not just J. Hultin who was disappointed in the attempt to unfreeze and “revive” the Spanish flu agent. There was more evidence of this kind. The failure, which has been widely described in the press, was also experienced by the Canadian anthropologist and geographer Kirsty Duncan (b. 1966).

The researchers presented their study to different societies and assessed the risk that the virulent virus “escaped” differently. J. Hultin discussed his plans, workflow, failures in a narrow circle of scientists.

K. Duncan, a 30-year-old Canadian, was born in 1992. After defending his doctoral thesis at the University of Edinburgh, by contrast, he spoke publicly about efforts to discover the pathogen in the remains of Spanish flu victims .

First, he analyzed a possible site for archaeological research, considered conducting research in Alaska, Siberia, Iceland.

In Alaska, he did not have as good a relationship as Hultin, he did not receive the slightest response to letters from Siberia, and Iceland proved to be the wrong place for such an investigation.

Eventually, he decided to conduct research in the northern Norwegian archipelago beyond the Arctic Circle in Spitsbergen, a small town in Lògygybbiene (Longyearbyen). A local teacher had kept records indicating that six young miners had died of the flu and mentioned their burial site.

K. Duncan received excavation permits, project funding, assembled an international team of 17 researchers, and focused on the safety of the study. Once infected, expedition participants could spread the virus again and cause fatal consequences.

1998 excavations began. Journalists discussed the excavations extensively and awaited sensational news.

However, after opening the graves and exhuming the bodies, it became clear that their lungs and brains were broken. The bodies were buried shallow.

K. Duncan is known in Canada as both a scientist and a politician. He has been a member of the Canadian Parliament since 2015. – Head of the Ministry of Science, later – the Ministry of Science and Sports.

Canadian Minister of Science Kirsty Duncan and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, 2017

He held this position until 2019. K. Duncan described the archaeological excavations in Norway and the Spanish influenza pandemic in 2003. in the book “1918. Hunting the Flu of 1918.

The goal was reached in 1997.

The defeats suffered by the scientists were painful, but the story was a success.

In 1997, when K. Duncan was collecting research material and planning an expedition, Hultin, 72, lived in Sán Fransìske and was constantly interested in virological discoveries and seeing scientific news.

One in 1997 opened the magazine in the morning Science read an article by Jeffery Taubenberger, researcher at the Department of Molecular Pathology at the Institute of Military Pathology in Washington, DC and co-authors, “Primary Genetics Description of the Spanish” influenza virus “(“Initial genetic characterization of the 1918 Spanish influenza virus. ”)

Article by Jeffery Taubenberger and co-authors.

Then Hultin thought that what he was trying to do was done: the virus was found, restored, detected. However, this was only the initial step in studying the viral genome.

J. Taubenberger and colleagues since 1995. investigated in 1918. September 26 In South Carolina, a sample of lung tissue from a 21-year-old soldier who died of pneumonia induced by the Spanish flu and recovered part of the virus’s RNA.

Americans not only carefully recorded epidemiological data, but since the Civil War, they have collected sets of pathological anatomical tissues that also contained parts of the lung tissue of those who died of Spanish flu, soaked in formaldehyde and “covered” with paraffin film .

However, it took time and cutting-edge technology to investigate the cause of the Spanish flu. After examining the material in this tissue file, J. Taubenberger restored part of the viral genome.

After reading Taubenberger’s article, Hultin thought he might try to find the virus in Alaska again. In a letter to Taubenberger, he asked if the scientist would examine the tissues of victims of the Spanish flu that he had brought from Alaska and if this could help identify the entire chain of RNA.

He feared that the young scientist would not endorse his proposal as “inadequate fiction,” but Taubenberger, who soon called him, admitted that the material would be useful.

It is incredible that after almost half a century, Hultin has achieved his goal. Immediately the week after the interview, he flew to Alaska and arrived at the Brevig Mission itself.

The town had changed. It was home to some 400 people, often unemployed but receiving significant state benefits. Instead of the dog sledding, the snowmobiles were close to the house.

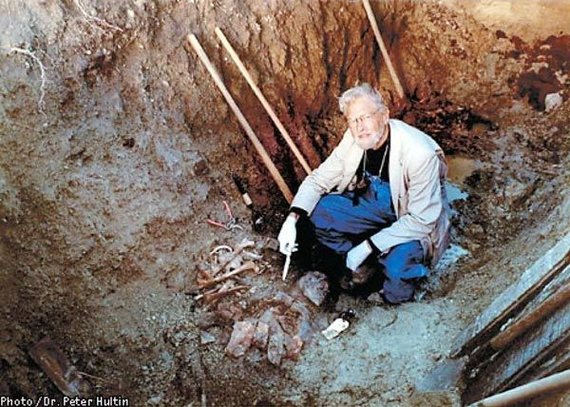

Johann Hultin’s Second Expedition, Brevig Mission, 1997

Past experience and known survivors helped Hultin obtain community consent to resume excavations at the same cemetery. Four local men helped him.

The first in 1951. During the expedition, the remains were damaged during the excavation of the cemetery and the thawing of the earth. As a result, Hultin was now disappointed that he couldn’t find the properly preserved lungs as he exhumed their bodies one after another. There seemed to be another frustration at play.

However, in the remains of a plump 20-year-old woman, the layer of fat protected the lungs and were adequate for the study. This time, the scientist had modern means to preserve tissue samples.

He kept tissues infected with the deadly virus in a preservative fluid. The remains, from which he took material so valuable to science, Hultin called Lucy, and they ended the expedition by erecting a new cross in the Brevig Mission Common Cemetery with the names of the victims of the flu pandemic.

This expedition, airline tickets, taxes on helpers planted $ 3,200. Upon his return to Sán Fransìsk, Hultin sent the virus-infected tissues through three different postal services to several members of J. Taubenberger’s team in Washington. In this way, he wanted to make sure that the research material did not disappear and reach the investigators.

The most virulent virus in human history traveled from Hultin’s suitcase from Alaska to San Francisco and then, as a simple mail, to a laboratory in Washington. When the virus escaped into the environment, it could spread and infect many people.

Ten days later, Taubenberger reported that the laboratory had received the package and that the tissues were in a position to be analyzed. A young Inuit woman named Lucy injured the lungs of a deadly virus and helped scientists rebuild the genome of the Spanish virus.

The researchers announced in 2005 the successful reconstruction of the Spanish influenza virus genome, which took ten years.

[ad_2]