[ad_1]

“You are no longer allowed to stay and must now voluntarily return to your home country or be deported,” the Irish Department of Justice and Equality said in a letter. Lily was informed that she has five days to inform the authorities of her decision.

Lily was flooded with a whole bouquet of emotions, which also penetrated through the protective suit she was wearing. Lily assures him that at that moment she just wanted to cry, but the accumulated tears had to be swallowed.

“I had to stay strong because of my residents. So I tried to smile, even though I felt an infinite amount of pain inside, “the woman tells CNN.

Lily, whose name, CNN says, has been changed for her safety, says she fled her native Zimbabwe over LGBTQ harassment. He arrived in Ireland in 2016.

All she wanted was to help others, so in Ireland, Lily was studying to become a health care assistant. Last year, Lily got a job in a nursing home and in the future she promises to study and get a nursing specialty.

During the coronavirus pandemic, Lily worked in a nursing home and did not work for just three weeks in April, when she became infected with the virus.

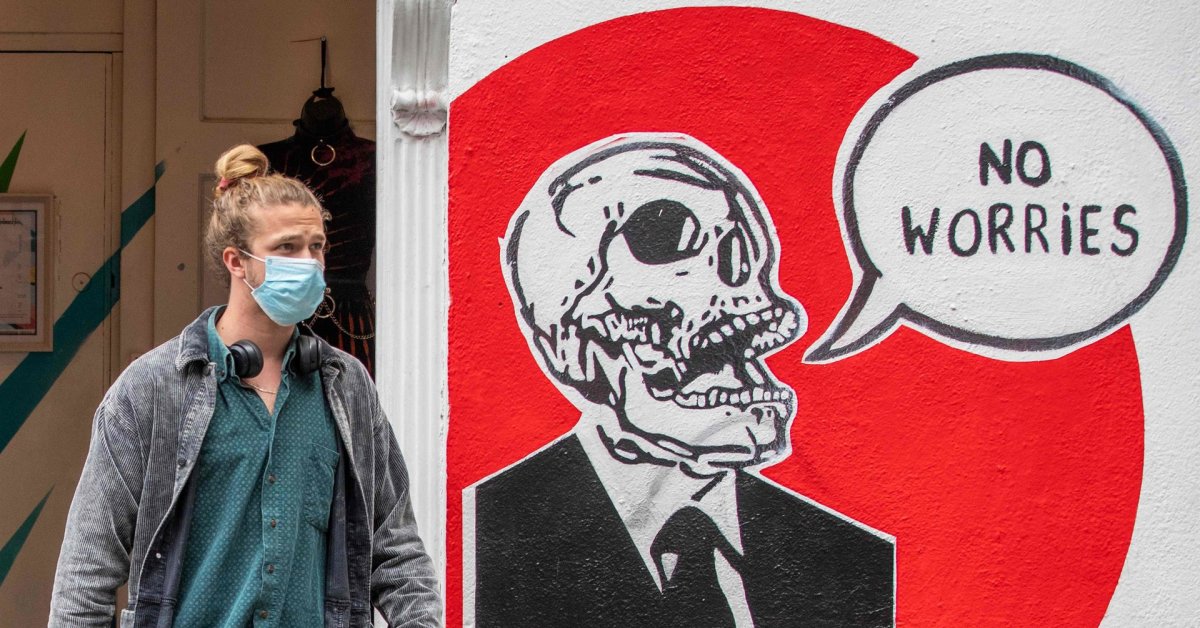

Scanpix Photo / Coronavirus in Ireland

Already at the beginning of the pandemic, the Irish Association of Nurses and Midwives reported that in Ireland, Covid-19 infection was more prevalent among healthcare workers in Europe.

As soon as she recovered, Lily went back to work. Over the months, she said she had seen the disease take the lives of the grandparents she cared for.

“There were so many people dying. It was incredibly hard to bear,” says Lily.

In Ireland, Covid-19 infection was more prevalent among healthcare workers in Europe

Now that she’s threatened with deportation, Lily says she feels like someone is writing the death warrant herself.

“They say frontline workers are heroes … But behind closed doors, they kick us out and send us back to the countries we escaped from,” he says.

A letter from the Justice Department to Lily was sent three weeks before a second national quarantine was introduced into the country to halt the rise in coronavirus infections and deaths. With this letter, Lily’s work permit in the country also expired, although she continues to work.

Constance, a health worker, whose name has also been changed for her safety, works in other nursing homes, but her situation is very similar.

In 2019, Constance’s request to stay in Ireland, again based on LGBTQ discrimination in Zimbabwe, was denied. Constance was told that her story doesn’t seem convincing because she is “not bisexual.”

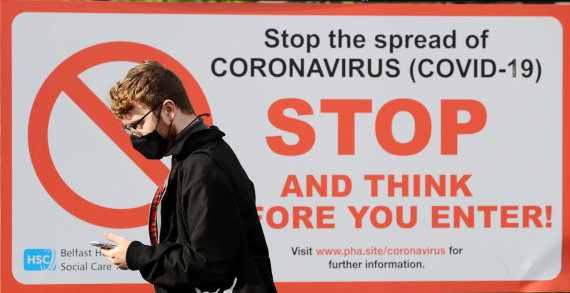

Scanpix Photo / Coronavirus in Ireland

The Irish Justice Department said in a response to CNN that they did not comment on specific immigration cases.

In another statement, the department stated that it was following the recommendations of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees “on applications for international protection based on sexual orientation or gender identity” and that training of social workers “is very complete and is in conjunction with the United Nations Refugee Agency.

Under the direction of the Department, each case is heard and decisions are made as soon as possible.

“This ensures that those who need our help and protection can get it as quickly as possible and start building their lives here feeling safe,” the department said.

When Constance’s application for permission to reside in Ireland was rejected, she appealed on “humanitarian grounds”. In this case, the examination of the application will take into account the character of the person, his conduct and the nature of the relationship with the State.

Given her many years of commitment to the most vulnerable people in Ireland, both before and during the pandemic, and the excellent recommendation from the employer that her work is necessary, Constance said she hoped her appeal would be successful.

However, on October 28 she received a letter announcing that her appeal had been rejected and that she would be deported. Constance assures that the rest hurts. The woman says that during the first quarantine, a public demonstration of the Irish authorities’ solidarity with healthcare workers has now fallen somewhere or been forgotten.

“Hundreds of thousands of congratulations”

In May, speaking to the Irish Parliament, then-Health Minister Simon Harris acknowledged the contribution of some 160 migrant health workers to the country’s health system and the country’s controversial asylum-seeker system.

Harris later said he gave those migrant health workers a “céad méle failte,” which means “one hundred thousand congratulations.”

But for those at risk of deportation, like Lily and Constance, his words now ring completely empty.

In its August report “Powerless: Direct Supply Experiences During the Covid-19 Pandemic”, the Irish Refugee Council called on the government to grant migrant health workers and others in the health sector “permission to stay. “as” recognition for his work and contribution to Irish society. “

CNN asked Ireland’s Department of Justice and Equality how many of the roughly 160 migrants working in the country’s health sector have had their asylum claims rejected since the pandemic began.

CNN has not received this information, but the fact that at least two healthcare workers are at risk of deportation amid a second national lockdown is a concern for migrant rights groups.

Bulelani Mfaco, a spokesman for the Movement of Asylum Seekers Irish (MASI), told CNN that the Justice Department had been “hostile to migrants” for a long time, but said it had no hope of reaching “such low levels” in the middle of a pandemic.

AFP / “Scanpix” nuotr./Koronavirusas

Mfaco added that many migrants in other professions also played an important role during the pandemic, in retail, as guards or cleaners, they did everything possible to keep the country and its economy afloat.

CNN contacted two migrants who worked in other professions, one who worked in the food service industry and the other who worked as a security guard. Both have received deportation letters in recent weeks.

In May, the Asylum Movement asked the government to recognize the contribution of these essential workers, stating that the Department of Justice “can, should and should allow undocumented people to live in the country and offer them long-term residence during a pandemic. regardless of current immigration status. “

The message now resonates in the Irish Parliament, with several lawmakers calling on the current Justice Minister to reconsider his position.

In an emotional speech last week, Sen. Eileen Flynn said it was “completely ridiculous” that healthcare workers faced deportation when the pandemic broke out.

“These women have risked their lives in this country. If you don’t show determination and devotion to this country, what will you show? … Those who live here should stay here,” she said.

Both Lily and Constance say they are currently preparing to appeal the deportation with their attorneys. Constance claims to have the support of an employer. Meanwhile, Lily said she had not yet shared the news with her leaders, despite constant fears that the Irish authorities could come and deport her from the country at any time.

Both women assure them that they will continue working. They must, as they say, “because the country needs them.”

[ad_2]