[ad_1]

Coincidence or not, but Matilda’s work finally came to the house on 16 Basanavičiaus Street in Vilnius, where she lived while studying. Approximately a dozen years after his death in 1987, these manuscripts fell into the hands of Professor Irena Veisaitė, a literary critic who survived the Holocaust and escaped from the Kaunas ghetto.

“It is a really fantastic story here. This never occurred to them, it happens, I don’t know, maybe it is the hand of fate or God. Look, this is not just a book, it is a monument,” said Professor I. Veisaitė while presenting Matilda Olkinaitė’s biography “Unlocked Diary” at the Book Fair.

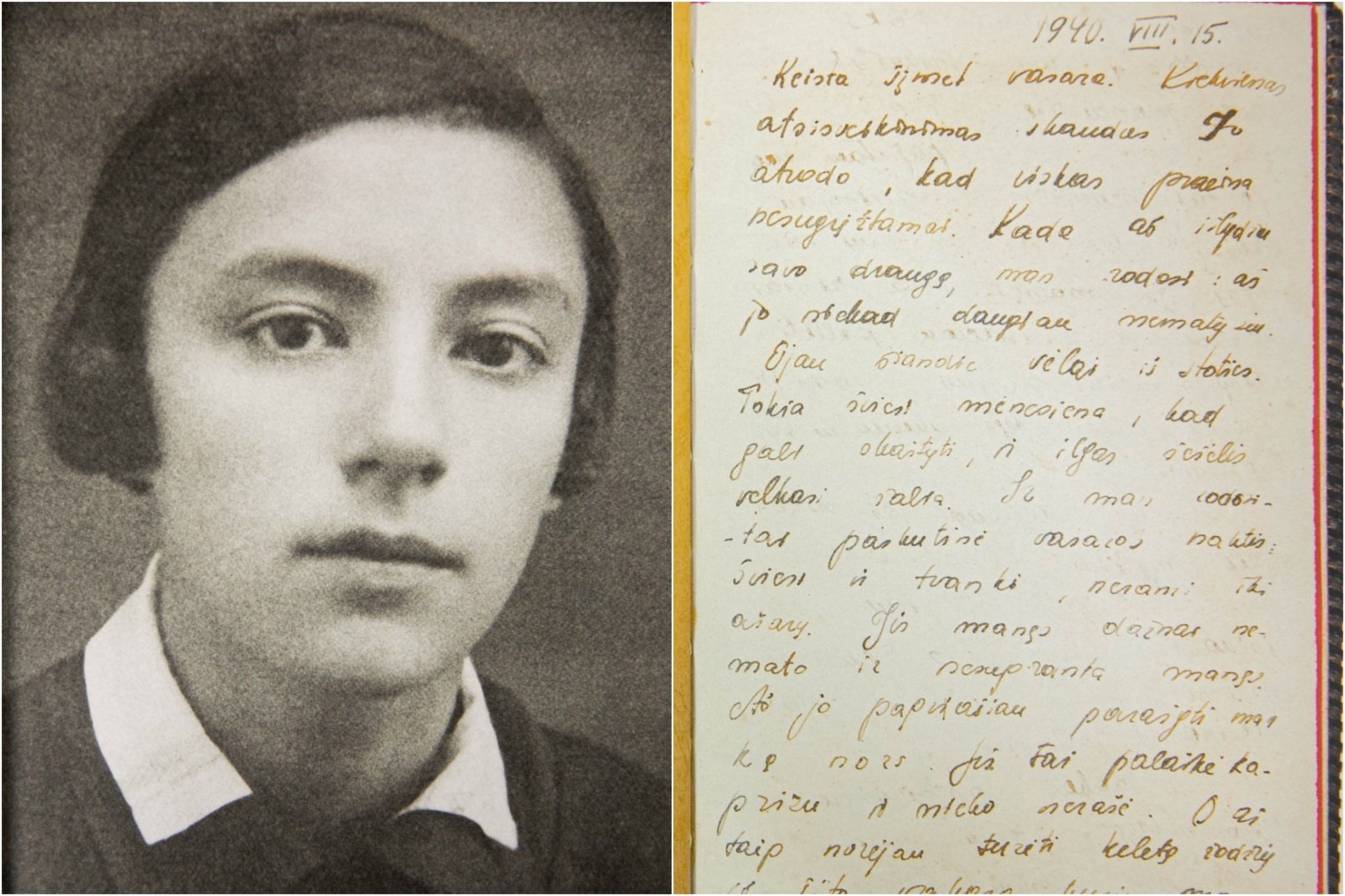

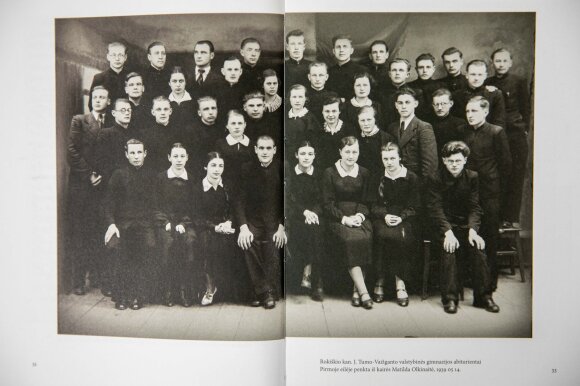

The tragic story of a girl and her family can hardly leave anyone indifferent. Having written poems in the perfect Lithuanian language since the age of nine, M. Olkinaitė could become a famous writer. Especially since he studied with well-known poets like Alfonsas Nyka Niliūnas, Vytautas Mačernis, he studied at Vincas Mykolaitis Putinas.

However, the Nazi occupation and those who pursued the regime’s unimaginable goals did not choose the victims and ruthlessly silenced the path of their lives only for the young poet who had started. What is even more shocking is that the Olkinai family, who lived in the small town of Panemunėlis near Rokiškis, could have survived, but made a very difficult decision not to risk other people’s lives and surrendered to their own executioners.

For the Lithuanians, the beginning of the war and the German occupation seemed a liberation from the “red plague”, from the horror of deportations. For the Jews, although they were transported to Siberia in cattle cars along with ethnic Lithuanians, Nazism meant death, and the Soviets and even deportation meant some chance of survival.

Prof. I. Veisaitė

Two families were shot and buried in a remote bog

As Laima Vincė Sruoginis, a writer and translator who studied the life of M. Olkinaitė, writes, in her book, the last day of the young poet’s life dawned in 1941. in July. That day, residents of the city of Panemunėlis saw a group of white-collar people, Lithuanians who collaborated with the Nazis, ride a bicycle on the village road leading to Kavoliškis.

“After leaving the bikes near the road … they started digging. It was bad (…), so they moved the shovels to the other side of the road and started working again on the peat bog, ”writes L. V. Sruoginis. This place is still called Sahara by the villagers.

Soon, according to the book, white-collar workers went somewhere and returned approximately an hour later with a horse-drawn carriage with captives sitting blindfolded.

“When they got to the hill, they were told to get out, because the horses no longer pulled the full carriages. The guards urged people to climb the mountain (…) “,” L.V. write about the suffering of the Olkin and Jofiai families. Stranded.

© DELFI / Josvydas Elinskas

According to the book, the entire journey of the two families to death, hidden behind a haystack, was followed by a girl of just eight years old, the daughter of a local farmer, since their farm was very close to the murder site. Already as an adult woman, she said she couldn’t see anything soon, but the screaming and yelling ran aside for a long time before the gunshots were finally heard.

“No one dared to approach the site of the massacre that day, only the next day Šarkauskienė and her neighbor went to see her. They found a lot of dirt. Šarkauskas sprayed it with a rake and realized that their bodies were covered by only a few centimeters of earth. They covered the remains of the remains with branches and poured a larger hill of earth to prevent the bodies of wild beasts from finding the bodies, “writes LV in the biography of the young poet, based on painful memories of locals stranded.

Two Panemunėlis families, Olkinai and Jofiai, are now known to have been killed separately from other arrested Jews.

“It is believed that the objective of the Jewish shooters was to rob the pharmacist and miller from Panemunėlis considered wealthy,” writes Mindaugas Kvietkauskas, the Minister of Culture and author of the book.

“He had to disappear, his name had to disappear,” he said at the Book Fair. According to the book, the exact location of the murder and burial of her and her family and another family was determined only in 2018, during an expedition of US archaeologists. USA And Lithuania.

Kvietkauskas Mindaugas

Admittedly, the Lithuanians who committed this heinous crime have not been specifically identified so far, although, as mentioned in the book, the locals name them by last name.

Growing up as an American Lithuanian, I believed for many years that it was the Nazis who valued Lithuanians for killing their Jewish neighbors with a gun. The truth was much more painful: Matilda’s killers were aware, they committed the crime with a clear understanding of what they were doing. According to the researchers, 23,000 Lithuanians collaborated with the Nazis at the time, although this did not reach one percent of the total Lithuanian population ”, L. V. Sruoginis describes the painful historical truth in the book.

Growing up as an American Lithuanian, I believed for many years that Lithuanians were worthy to kill their Jewish neighbors with a Nazi weapon. The truth was much more painful: Matilda’s killers were aware, they committed the crime with a clear understanding of what they were doing.

L. V. Sruoginis

A closed blog is a mysterious love story.

Before the start of the war, M. Olkinaitė lived in Kaunas, later in Vilnius. Here he studied at the University of Vilnius, studying French language and literature. Matilda is known to have lived for some time in the same house on Basanavičiaus Street, where prof. I. Veisaitė.

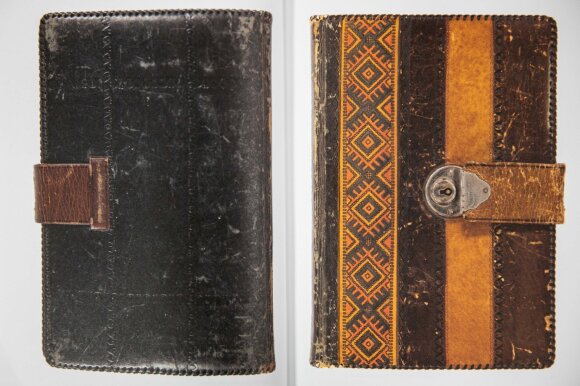

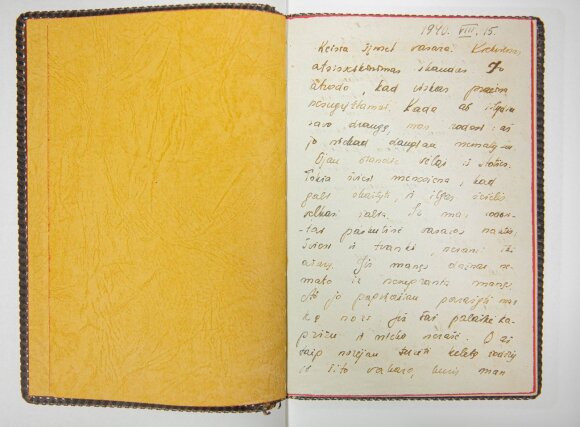

It was here that the girl finished writing her sensual diary, which was later discovered by a literary critic after receiving a book of poems from M. Olkinaitė. It was delivered to the professor by a Soviet colonel.

As the teacher said in her presentation of the book, she no longer remembers how the diary, decorated with leather covers and closed, fell into the hands of a Soviet colonel because he had lost his collected notes on a young poet somewhere.

“Most of Matilda’s diary is about love for a young man, whose identity remains a mystery,” writes L. V. Sruoginis.

© File photo

Throughout the blog, a nineteen-year-old girl never mentions her loved one’s identity, and is mentioned everywhere. Perhaps yes, according to the authors of the book, M. Olkinaitė tried to protect him by feeling the imminent threat.

Although today the researchers of the young poet’s work are fascinated by the tones of Salomėja Neris and Bernardas Brazdžionis reflected in their poems, M. Olkinaitė did not hide his resentment in the newspaper about the creators who glorified the communist regime.

“It just came to our attention then. The world took to the streets, put a red scarf in his pocket and shouted. Poems by Salomėja Neris, Liudas Gira. I don’t know how normal people can write like this,” lamented M. Olkinaitė on his blog.

The date of the last journal entry, written in his biography book, is 1941. February. The poet of the book did not finish anyway, there are many blank pages.

He returned to his homeland

It is not known exactly why and when the girl from Vilnius decided to take her back to her parents’ house, but it is believed that she did it in 1941. in June, after the outbreak of the Second World War in Lithuania.

As can be seen in the surviving journal of M. Olkinaitė, before taking home, the poet still dreamed of her first book, but realized that the Soviet system was unfavorable for her work.

“When he returned to his hometown, Matilda was unable to find a safe haven there. As early as 1941. In early July, the Jews of Panemunėlis, the Olkinai, Karabelnik, Jofiai families and others, were arrested (…) by the called white-collar workers and initially locked up in a detention center near the railway station, and later in the Panemunėlis mansion cemetery, “writes M. Kvietkauskas.

Genovaitė, a good friend of Grunė, M. Olkinaitė’s sister, also shared her memories of that time with investigators.

“The conditions there were terrible, manure everywhere, rotten potatoes, beets. They spread white sheets on the straw, that’s how they lived …”, Genovaitė, who was seven years younger than Matilda, recalled the cruel period.

© File photo

At just 12 years old, Genovaitė brought food to incarcerated families. She said her mother was very concerned about all of them, so she was constantly doing something. According to Genovaitė, Kumetynas was guarded by a single guard, he allowed her twelve-year-old children, she and Matilda’s sister, Grune, to walk and play in the field.

Genovaitė is convinced that the families could have easily escaped, but he did not believe that there was such danger. Only the last conversation with a good friend, investigators told the woman, was extremely memorable.

“The last day I went out for a walk with Grune, she said she heard they were going to shoot her. I hugged Grune and said, “Who will kill the innocent children?” Grune replied, “And I don’t think they’ll shoot us,” recalled the girl’s girlfriend killed in a painful conversation.

“The last day I went out for a walk with Grune, she said she heard they were going to shoot her. I hugged Grune and said, “Who will kill innocent children?” Grune replied, “And I don’t think they’ll shoot us.”

excerpt from the book

To save the pastor, they surrendered

Matelionis, the pastor of Panemunėlis, who had previously been helped by Matilda’s father to heal a language defect, also tried to save the Olkinai family from doom. According to M. Kvietkauskas, the priest protected the family at the rectory, but soon the rumors about the Jews hiding here in the small town also reached white-collar workers.

Soon throughout the city, as evidenced by the memories of the locals, announcements were published announcing that not only Jews would be punished with death, but also those who helped them. Matilda’s father, Noah Olkin, who saw one of those Nazi warnings, is believed to have made the decision to surrender and not risk the life of his savior.

“Probably then, after making this fatal decision, Matilda handed her notebook to the pastor, who hid it under the main altar of the Panemunėlis church,” writes M. Kvietkauskas.

Of course, Olkin’s rescuer was not an easy path: the Soviets deported him to Siberia for many years, but even the priest questioned by the occupants never mentioned the protected work of a young but brutally silenced girl.

© File photo

This notebook was discovered many years later by a dissident writer and organist who worked at the Panemunėlis Church. At that time, he already knew literary critic Irena Veisaitė, because she was the supervisor of his dissertation.

“One day he comes to me with a notebook, which you will see in this book, which contains the poems of Matilda Olkinaitė. There were quite a few of them, including prose and its essays. You know, I looked at everything and how Class’s ashes hit my heart, my house. I could not fall asleep for three weeks, I could not agree with the idea that she was dead and that I was alive, “said the teacher sensitively in the presentation of the book.

He said that when Sąjūdis started, his research was stopped, but this work was taken over by the Lithuanian American J. V. Sruoginis.

The writer says that as soon as she wrote the first publication about this poet in English, she received many reactions from around the world. M. Olkinaitė even began to call herself Lithuanian Anne Frank.

Neringa Danienė, director of the Rokiškis Theater, did not let the girl forget her tragic fate, but, according to Matilda’s diary and a book of poems, in 2016 she wrote the play “Silent Mutes”.

After all, this cruelty spread at that time as a universal phenomenon across Europe, and it would be a mistake to blame one nation or another. A nation can never be guilty because there are different people in each nation, there are murderers and saviors.

Prof. I. Veisaitė

During the story of one family, all the tragedy that took place in Lithuania arose

In his book Unlocked Diary, J. V. Sruoginis writes that while gathering information about the young poet, he repeatedly spoke and listened to the story of his own life with Professor I. Veisaitė, who began this work. The writer acknowledges that the question of why these innocent people were executed remains relevant and painful to this day.

“Regarding the first Soviet occupation, it is necessary to understand that at that time the existential situations of ethnic Jews and ethnic Lithuanians were very different. For Lithuanians, the beginning of the war and the German occupation seemed a liberation from the” red plague “, from the horror of deportations. For the Jews, although they were transported to Siberia in cattle cars together with ethnic Lithuanians, Nazism meant death, and the Soviets and even deportation meant some possibility of survival. We should stop blaming each other for this, “the writers told I. Veisaitė about the extremely complicated historical period that affected both nations.

Irena Veisaitė

© DELFI / Josvydas Elinskas

In the book, the teacher herself speaks openly and sensitively about the murders of Jews in Lithuania.

“Through Matilda’s work, I experience all the tragedy that has taken place in Lithuania. It hurts so much so far. I can’t imagine how people could have been persuaded to kill even children. After all, until then, everyone lived in peace. My grandfather, who lived in Babtu before the war, also agreed with everyone that his neighbors loved and respected him, and had never heard anything bad about Lithuanians. Why did he have to be killed? Incomprehensible.

After all, this cruelty spread at that time as a universal phenomenon across Europe, and it would be a mistake to blame one nation or another. The nation can never be guilty, because there are different people, assassins and rescuers in each nation, “writes I. Veisaitė.

It is strictly prohibited to use the information published by DELFI on other websites, in the media or elsewhere, or to distribute our material in any way without consent, and if consent has been obtained, DELFI must be cited as the source.

[ad_2]