[ad_1]

During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union built more than 400 nuclear submarines, considered a “silent service” that allowed both to retaliate, even if missile shafts and strategic bombers were destroyed during a first sudden attack. Just 97 kilometers from the border with NATO member Norway, the Arctic port of Murmansk and the surrounding military bases have become the center of the Soviet Union’s nuclear fleet and icebreakers, as well as spent nuclear fuel. highly radioactive.

With the fall of the Iron Curtain, the consequences of such a strategy became clear. For example, in Andrejevo Bay, where in 1982 600,000 people leaked from the nuclear waste storage facility into the Barents Sea. The toxic water, the spent fuel from more than a hundred nuclear ships, was stored in rusty tanks just outside.

Fearing pollution, Russia and Western nations, including Britain, undertook large-scale clean-up work and spent nearly a billion dollars. pounds ($ 1.3 billion) to safely dismantle 197 Soviet nuclear submarines, repair 1,000 radio beacon strontium batteries, and begin removing fuel and debris from Andreyev Bay and three other dangerous coastal locations.

Soviet nuclear submarines

As in other countries, unfortunately, Soviet nuclear waste was dumped directly into the sea, now attention has also been paid to this damage. In 2019, a feasibility study by a consortium led by UK nuclear security firm Nuvia revealed that there are 18,000 people in the Arctic Ocean. radioactive facilities, including up to 19 ships and 14 reactors.

Although the level of radiation emitted by many of these objects has almost reached the background level (due to the layer of mud formed on them), the study found that a thousand of these objects still emit a higher level of highly penetrating gamma rays. 90 percent. they are being distributed over six sites that will be built by Russia’s state nuclear power corporation Rosatom over the next 12 years, said Anatoly Grigoriev, the corporation’s head of international technical support. These will be two submarines and reactor compartments of three submarines and the Lenin icebreaker.

“We believe that even the extremely low probability of leakage of radioactive material from these facilities represents an unacceptable risk to the Arctic ecosystems,” Grigoriev said in a statement.

To date, a clean-up mission of this magnitude has never been carried out at sea. Relocation of the reactor compartments will take place in extremely cold waters, where such operations are only safe for three to four months out of the year. Deploying the two nuclear submarines will be an even greater challenge, as they both emit a million curls of radiation, equivalent to about a quarter of the radiation that spread in the first month after the accident at the Fukushima nuclear power plant.

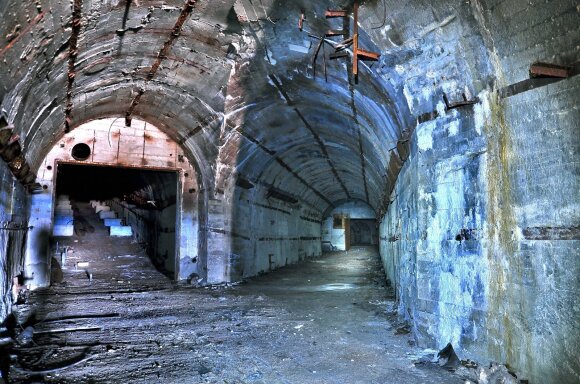

Soviet submarine hangar

One of these ships is the K-27, which was once called the “goldfish” due to the high cost of the work. The 118-meter-long attack submarine (such ships were designed to hunt other submarines) ran into problems with liquid metal-cooled experimental reactors, one of which lasted six years later and fatally irradiated nine sailors, since its commissioning. in 1962.

In 1981 and 1982, the fleet filled its reactor with asphalt and sank the ship to a depth of only 33 meters east of the New Earth archipelago. Even drowning him wasn’t easy. K-27 eventually sank, it was ensured that all measures had been taken during the process so that its remains did not pose any danger until 2032.

Another incident is of much greater concern. The 107-meter long submarine K-159 was in operation from 1963 to 1989. The ship unexpectedly sank, along with 800 kilograms of spent uranium fuel on the seabed over the fishing grounds and shipping lanes north of Murmansk.

Thomas Nilsen, editor of The Barents Observer, called the submarines a “slowing Chernobyl seafloor.”

A sunken Russian submarine

Ingar Amundsen, Head of International Nuclear Safety at the Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority, agrees that the question is when and not whether sunken submarines will pollute the waters (if left where they are now).

“They contain large amounts of spent nuclear fuel, which will undoubtedly be released into the environment in the future, and we know from experience that even small amounts of pollution, or even rumors, can cause problems and economic consequences for the fishing industry and marine products. “. , He said.

Damn august

Sergei Lapa was born in 1962 in Rubtsovsk, a small town in the Altai Mountains near the border with Kazakhstan. Although he was thousands of miles from there to the nearest ocean, attending a local boat modeling club, he became very interested in the profession of seaman. After graduating from school, he entered the Academy of Marine Engineering in Sevastopol, Crimea. The tall, athletic, forward-thinking student was assigned to the fleet’s most prestigious service position – the Northern Submarine Fleet.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the military situation began to deteriorate, as revealed to the world by the Kursk submarine tragedy, when the ship sank in August 2000, killing 118 people.

S. Lapa was in charge of the ship K-159, which has been rusting since 1989 at the dock in the isolated town of Ostrovnoy, where the Gremicha military base of the northern Russian navy operates. On the morning of August 29, 2003, a delayed order was received to tow the sunken K-159, which was tied with ropes to four 11-ton pontoons (not submerged during the operation), to a base near Murmansk where it was I would dismantle the ship. The decision was made despite the forecast of extremely windy weather.

Soviet submarine hangar

The reactors were shut down, so S. Lapa and his team of nine engineers controlled the ship by lighting flashlights. When the ship was towed, the ropes holding it to the pontoons broke in the stormy sea near Kildine Island immediately after midnight, and after half an hour the water began to sink into eight compartments. With headquarters increasingly delayed in deciding to launch an expensive rescue operation by dispatching a helicopter, the ship’s crew tried any way to keep the ship afloat.

2.45 pm Mikhail Gurov sent the last radio message: “Semianos, do something!”, But when the lifeboats reached site K-159, they were already lying on the seabed near Kildine Island. Of the three sailors who managed to escape, only one survived: Senior Lieutenant Maksimas Cibulskis, whose leather jacket filled the air and kept him above the water.

Russian newspapers of the time wrote that another nuclear submarine sank during “bloody” August. This incident alone did not cause as much of a stir as the Kursk tragedy. The fleet continued to promise relatives of the victims that a K-159 would be erected next year, but the project was still delayed.

After 17 years, at least the bones of the crew members should have survived in the submarine, says Lynne Bell, a forensic anthropologist at Simon Fraser University. But the families of the victims have long lost hope of getting them back.

“It would be at least somewhat easier for all of his loved ones if his parents and men were buried instead of lying in the hull at the bottom of the sea,” says Dmitry, Gurov’s son. “No one believes that more will happen.”

Soviet submarine project 615 in Krasnoyarsk

Itar-Tass / Scanpix

However, the situation has changed as Russia’s interest in the Arctic and its crumbling Soviet military cities and ports has revived. Since 2013, seven military bases and two oil tanker terminals have been built in the Arctic under the ongoing North Sea Highway project (which should provide a shorter route to China, and Vladimir Putin promises to transport 80 million tons of cargo on this route by 2025). . The K-159 is at the bottom of the sea at the eastern end of this route.

Although radiation “dissolves” rapidly over a large area of the oceans, even small amounts can accumulate in living things at the top of the food chain due to bioaccumulation. And then it would also enter the human body.

The economic consequences for the Barents Sea fishing industry, which supplies most of the cod produced in UK fish and potato taverns, “could be more serious than the environmental consequences,” says Hilde Elise Heldal, a researcher at the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research.

Their research shows that if all the radioactive material from the K-159 reactors were to enter the environment at once, the level of cesium-137 in the muscles of cod in the eastern Barents Sea would increase by at least a hundredfold.

Soviet submarine hangar

Such a level would not exceed the limit set by the Norwegian government after the Chernobyl accident, but it would be enough to scare consumers. For example, more than 20 countries have still banned seafood from Japan, although research shows that dangerous amounts of radioactive isotopes were not found in fish caught in the Pacific Ocean after the 2011 accident at the Fukushima nuclear power plant.

Lifting a submarine during a possible accident could damage the reactor, potentially mixing different elements, setting off an uncontrolled chain reaction and causing an explosion. In this case, the radiation level in the fish could exceed the norm a thousand times. And if this were to happen over water, the radiation would affect land animals and humans, according to another study by the Norwegians. In that case, Norway would have to suspend trade in products such as Arctic fish and venison for a year or even more.

It is strictly prohibited to use the information published by DELFI on other websites, in the media or elsewhere, or to distribute our material in any way without consent, and if consent has been obtained, it is necessary to indicate DELFI as the source.

[ad_2]