[ad_1]

The fact that the vaccine prevented the new coronavirus from multiplying in the nasal mucosa is considered particularly important in preventing the virus from spreading through air drops.

This was not accomplished by testing a vaccine developed by the University of Oxford, although in monkey experiments it prevented the infection from developing in the animals’ lungs and causing serious disease.

In the Moderna rhesus trials, three groups of eight animals each received either placebo or two different doses of the vaccine, 10 or 100 micrograms.

All of the vaccinated monkeys developed high concentrations of antibodies that neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 region of the coronavirus, allowing the infection to enter the cells.

It should be noted that in monkeys exposed to higher and lower doses of the vaccine, the concentration of antibodies produced was higher than that observed in humans with COVID-19.

The study authors reported that the vaccine also stimulated the production of T lymphocytes in the immune system. This is likely to have led to a stronger overall immune response.

The researchers were very concerned about the assumption that the vaccines being developed could work contrary to what was expected: exacerbating the disease rather than suppressing it.

A vaccine-related respiratory disorder called VAWER is believed to be crucial in activating the production of specific T lymphocytes, Th2. However, when the Modern vaccine was tested, the production of these cells in the body was not stimulated, so it can be considered safe.

Four weeks after the second vaccine injection, the monkeys were exposed to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, both nasal and directly through the lungs.

Two days later, virus replication was not detected in the lungs of seven of the eight monkeys analyzed. The same situation was observed in the highest and lowest dose groups of animals affected by the vaccine.

At that time, the virus had spread to the lungs of the eight monkeys that received placebo alone.

No detectable amounts of coronavirus were detected in the nasal cavity of any of the eight rhesus patients who received the highest dose of the vaccine two days after inoculation.

“This is the first time that an experimental COVID-19 vaccine with non-human primates has shown such abrupt control of the virus in the upper respiratory tract,” said the US National Institutes of Health, which contributed to the vaccine.

The COVID-19 vaccine, which prevents the virus from multiplying in the lungs, would prevent severe cases of the disease and reduce the risk of transmission of the virus if the infection in the nasal mucosa can be suppressed.

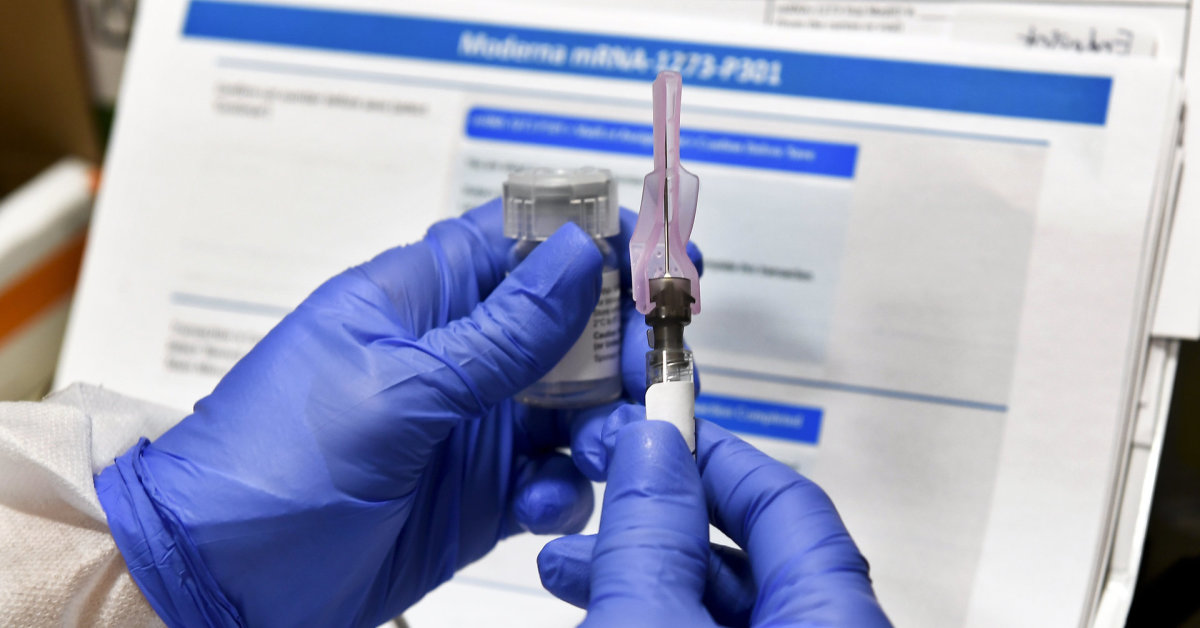

The Modern vaccine uses a part of the virus’s RNA that encodes the genetic information necessary to produce a protein that forms the so-called spikes of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Derivatives of the spinous coronavirus envelope allow the infection to penetrate the cells of the human body, but the protein that makes them up is considered relatively harmless.

The advantage of this technology is that it is not necessary to produce the virus proteins in the laboratory, which speeds up the mass production of the vaccine.

Both the Modern vaccine and the vaccines developed by the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca are currently being tested in humans.

[ad_2]