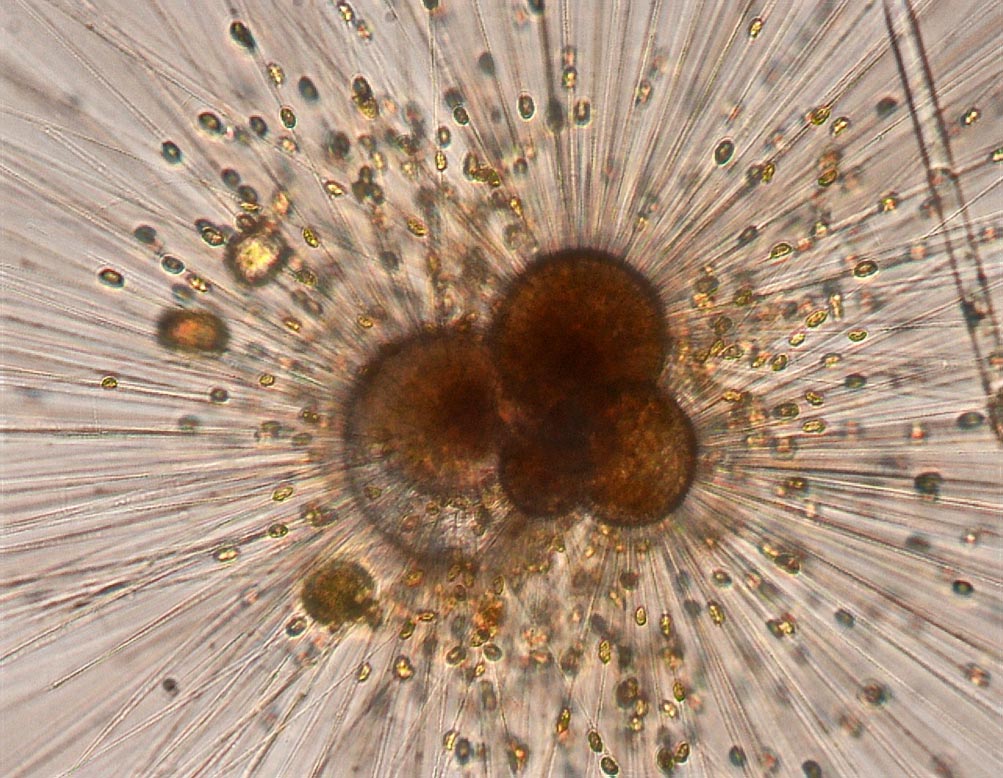

The living foraminifera, a type of marine plankton, was developed by researchers in a laboratory culture. To reconstruct past atmospheres, fossil specimens are collected from deep ocean sediments. Credit: Barbell Heinish / Lemont-Doherty Earth Observatory

The closest analogues of modern times are no longer so close, study finds.

A new study of antiquity, considered the closest natural analogue to the era of modern human carbon emissions, has found that large-scale volcanoes sent large waves of carbon into the oceans for thousands of years – but that nature did not match what humans are doing today. . This study estimates that humans can now introduce the element three to eight times faster, or maybe even more. The consequences of life on both water and land are potentially devastating. The findings appear in the journal This Week Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Researchers on Columbia UniversityThe Lemont-Doherty Earth Observatory investigated the ocean conditions.65..6 million years ago, known as the Palaeo-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) at the time. Earlier, the planet was already much hotter than it is today, and PETM’s high CO2 levels brought temperatures to a further 5 to 8 degrees C (9 to 14 degrees F). The oceans absorb large amounts of carbon, stimulating chemical reactions that caused the water to become highly acidic, and killing or damaging many marine species.

Study co-author Barbel Hinish obtained foraminifera, eight miles from Puerto Rico, near sea level. Samples were brought back to the laboratory under controlled conditions. Credit: Laura Haynes / Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

Scientists have known about the PETM carbon surge for years, but are still undecided as to what caused it. Aside from volcanoes, hypotheses include the sudden dissolution of static methane (which contains carbon) from sea-floor mud or collisions with comets. Researchers are also unsure of how much carbon dioxide was in the air and how much the oceans took in that way. The new study reinforces both the volcanic principle and the amount of carbon released into the air.

Laura Haynes, a leading author of research as a graduate student at Lamont-Doherty, said the research is directly relevant today. “We want to understand how the Earth system can now respond quickly to CO2 emissions,” he said. “PETM is not a complete analogue, but it is the closest thing to us. Today, things are moving very fast. “Haynes is now an assistant professor at Vasar College.

So far, the marine study of PETM has been based on obscure chemical data of the oceans and research on assumptions based on a certain degree of assumptions that researchers have fed into computer models.

The authors of the new study met more directly on the questions. They did this by culturing marine organisms with small shells called fora raminifera in seawater that they created similar to the highly acidic conditions of PETM. They noted how organisms took element boron into their shells during growth. They then compared these data with the analysis of boron of fossil foraminifera extending into the tissues of the Pacific and Atlantic Ocean-floor core. This allowed them to identify carbon-isotope signatures associated with specific carbon sources. This suggests that volcanoes are the main source – perhaps with the opening of the great Atlantic Ocean, and the separation of North America and Greenland from Northern Europe, with large eruptions centered around what is now Iceland.

Researchers say that carbon pulses, estimated by others to last at least 1,000,000 to 1,000,000 years, are about 1.9% in the ocean. qurillion trillion metric tons of carbon added – a two-thirds increase over their previous content. This carbon would have come out of CT2 which could have recovered from the eruption, the burning of the surrounding sedimentary rocks and some of the methane. As the oceans absorbed the carbon in the air, the water became very acidic, and remained that way for thousands of years. There is evidence that many of these deep sea creatures and perhaps other marine life have died as a result.

Today, human emissions of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere are causing skyscrapers and the oceans are again absorbing much of it. The difference is that we are presenting it faster than a volcano – in decades instead of a thousand. Atmospheric levels have risen from 280 parts per million in the 1700s to about 415 today, and they are on a rapidly rising path. Atmospheric levels would be higher if the oceans did not absorb so much. As they do, rapid acidification begins to strain marine life.

“If you add carbon slowly, living things can adapt. “If you do it too fast, it’s a really big problem,” said Barbell Hinishe, co-author of the geometric study at Lamont-Doherty. She pointed out that even the very slow pace of PETM led to large-scale deaths in marine life. “The past has seen some really terrible results, and it’s not progressing well for the future,” he said. “We are comparing the past, and the consequences will be very serious.”

Ref: 14 September 2020, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.