AAs a legal term, “protest” refers to a sexual assault victim’s first admission, testimony that initiates a police investigation, a process more familiar to most Americans through television procedures such as Law & Order : SVU than personal experience. On the big and small screen, this appears to be a straightforward process, especially if the person yelling is a child – register it, believe it, investigate, catch, process. So it seems in July 2013, when a four-year-old boy told his parents, who then reported to police in Williamson County, a suburb north of Austin, Texas, about the sexual assault of a high school student who named as Greg.

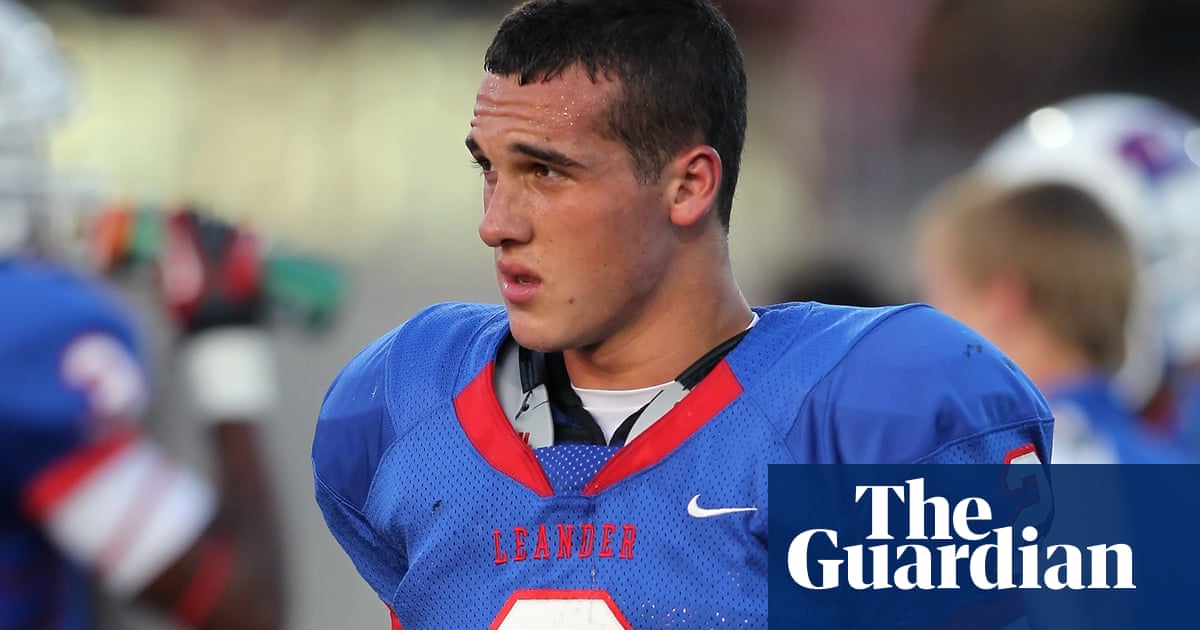

Greg Kelley, then a 17-year-old rising youth and star of the Leander High School soccer team, was immediately arrested.

It seemed like a clear case: Kelley lived with a friend’s family to maintain her residence in the district, in a house that also housed the home daycare that was attended by a four-year-old boy. Police soon reported another protest from another four-year-old daycare assistant. Kelley maintained his innocence but was convicted in 2014, at the age of 18, on two counts of aggravated sexual assault of a boy and sentenced to 25 years in prison without the possibility of parole.

But as documented in the five-part Showtime Outcry series, the case was not an open deal. After his conviction, hundreds of people, particularly high school classmates, in Leander and neighboring Cedar Park protested around Kelley’s innocence, not the answer you would necessarily expect from someone accused of sexually assaulting young children, no matter how much. High your profile in the quasi-religion that is Texas high school football.

A counter group gathered around the cause of believing testimonies of sexual assault. He believes in children versus he believes in the man who proclaims innocence and a railway conviction. However, as Outcry reveals, the case was much more twisted than a small polarized city; Over the course of five episodes and three years of filming, Greg Kelley’s story unfolds in real time, with some participants experiencing big turns and shocking news on camera, to reveal an accusing, thorny, hyperlocal but profoundly misbehaving saga. worrying. and a failed investigation, a confusing conviction process, and the misunderstood psychology of childhood confessions.

Outcry director Pat Kondelis lives in Williamson County, but did not hear about the Kelley case until a friend suggested that he investigate it while presenting another project, Disgraced, at South by Southwest in 2017. At first, “initially was not”. I’m not excited to do it, ”he told the Guardian. “There was so much information that people were giving me, and I didn’t know what I could believe, what I should believe. It was very different, from a development process, to anything else we’ve done. “

He was reunited with Kelley’s family, desperate for an external look at the case. When Kondelis started filming in 2017, Kelley had spent three years in prison and “we had no idea where this story was going to go,” Kondelis said.

However, he did know about the reputation of Williamson County Police, an area known for its unrelenting law enforcement (the county drew national attention in 2014 for charging a 19-year-old man who made marijuana brownies on felony charges life-threatening prison terms) and high-profile involuntary justice cases (such as Michael Morrison, who served 25 years in prison for a murder he did not commit after Williamson’s prosecution withheld evidence. He was released and exonerated in 2013). At the time of Kelley’s arrest, the “throw the book to people” attitude was something the Williamson County Police wore “as a badge of honor – not done here.” And if you do, you’re going to pay, ”said Kondelis.

However, early in the series, a change in county officials allowed Kondelis, the new district attorney, Shawn Dick, and Kelley’s substitute attorney, Keith Hampton, to investigate the case and a possible appeal. “Every interaction I had with Williamson County in the three years of doing this was positive,” said Kondelis. “They were open and transparent, and that was not what I expected.” Without spoiling too much, the series unfolds as the filmmakers experienced it, which Kondelis says was “a roller coaster … one day you feel pretty sure you know what happened, and the next day something happens and totally changes. Opinion “- The new examination of Kelley’s conviction revealed surprising incompetence, misconduct, and general misunderstandings about the veracity and techniques of child trauma interviews.

The officer charged with investigating the four-year-old boy’s protest did not even visit the scene of the alleged crime. Kelley’s attorney, hired at the suggestion of the daycare owner, was revealed to have troubling conflicts of interest. A possible alternative suspect was not fully investigated, among other disturbing disclosures about the county’s handling of the case. Prosecutors changed the alleged deadlines to comply with the alleged accounts.

“It was a constant back and forth,” Kondelis said of the filming experience for three years. “You have to be open-minded and consider all the possibilities, because you still don’t know all the information.”

All along, the case drew significant and sustained attention from local media, especially after Kelley was released on bail in 2017 pending the reopening of the case, and exacerbated by his status as a local soccer star: few things attract. America’s attention as the story of potential frustrated athletics on behalf of young men. Outcry also explores both sides of the fervent support in the case, on behalf of the “Pray for GK” group who believed (some based on personal connection, some based on popularity) in Kelley’s innocence, especially her mother. , Rosa and his girlfriend, Gaebri Anderson; and victims’ rights advocates who understood that a discredited sexual assault claim could threaten the seriousness of all others.

“You had camps on both sides that were fully excavated and both believed they were fighting a fair fight,” said Kondelis. “Each side digs its heels into its belief that they are protecting the innocent.”

However, he noted, details from Leander, Williamson County and Texas soccer distorted the visibility of the case. “If Greg hadn’t been Leander’s high school football star, he wouldn’t have received as much support as he did,” said Kondelis. “If this didn’t happen at Williamson, where there is a long history of wrongful conviction, either, he wouldn’t have gotten the support he did.”

Ultimately, the critical and nuanced reexamination of Kelley’s case, as well as the evidence-based reevaluation of child protest interviews, high suggestibility cases, the ease with which investigators can induce a false memory or fabricated confession , led to a resolved justice for Kelley (the resolution of the case is public information, but there are no spoilers here). Although the case, like any other, is specific and messy in its details, “there is a lot to learn there,” said Kondelis, “and I hope [people can] get a better idea of how these investigations and prosecutions really work, because they are so different from what we’ve been programmed to see on television and in movies. “You assume competence; you assume easily delineated narratives.

“Most Americans believe that if a serious crime were to happen to a family member, prosecutors and the police are going to abandon everything and attack a case like that as if it were a member of their own family,” said Kondelis. “This is not how it works.

“It certainly is not what happened in this case.”

.