[ad_1]

Opinion: Hunger: the story of the Irish famine is a timely reminder of the event’s central place in Irish history

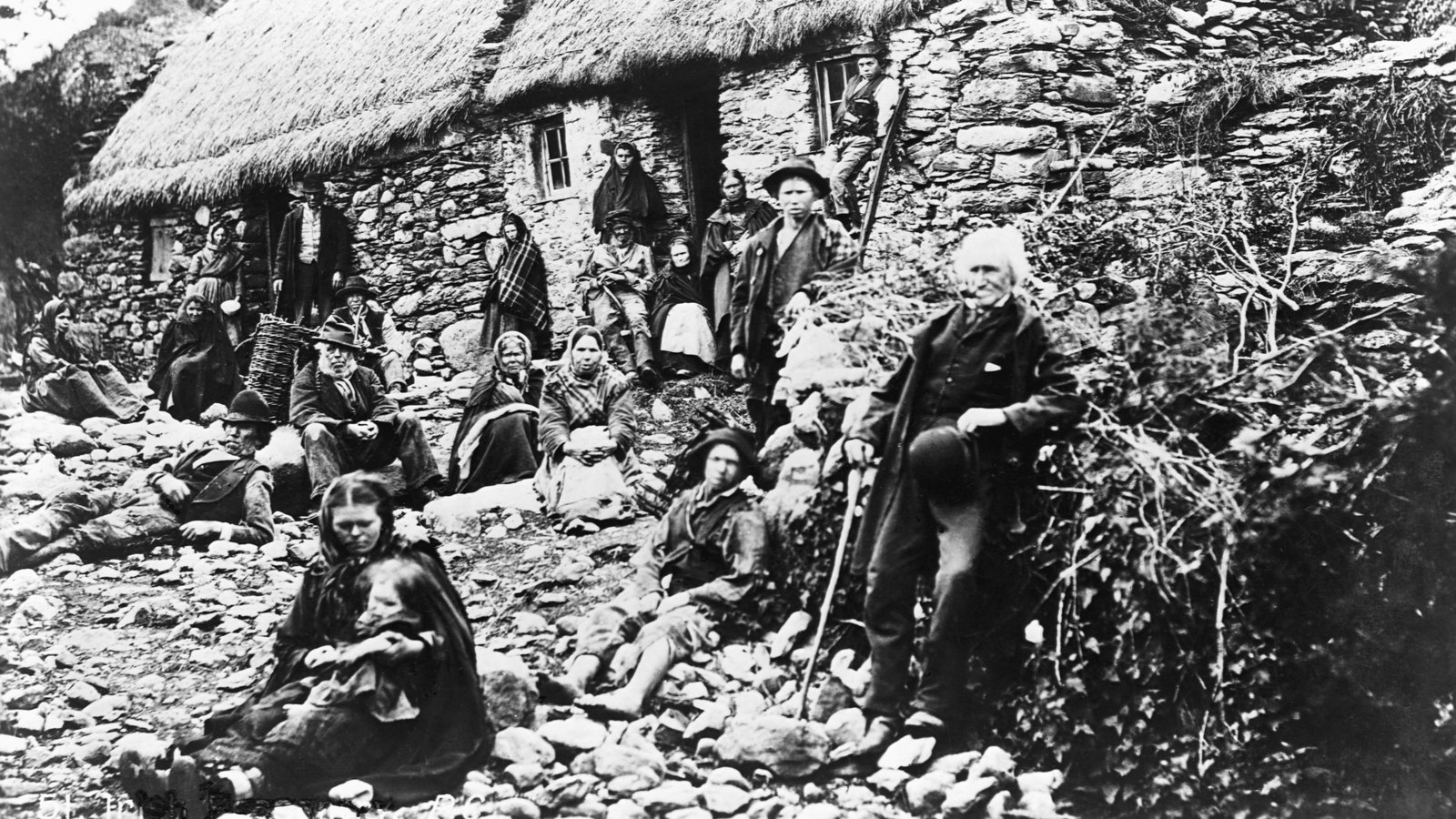

This year marks the 175th anniversary of the start of the Great Irish Famine (1845-1852) which resulted in the death of more than a million people and the dispersion of one and a quarter million across the world. It was a large-scale humanitarian disaster with tragic consequences, especially for those classes at the bottom of the social ladder: the landless peasants and workers whose families depended almost entirely on the potato for their survival.

While it swept across the island in terms of its impact, the famine was particularly devastating to the western and southern counties of the country. One of the great strengths of Atlas of the Great Irish Famine (Cork University Press, 2012), which reports Hunger: the story of the Irish famine documentary was the fact that it exposed the local, regional, national and international dimensions of the hunger narrative. As Cormac Ó Gráda et al they point out, “famines are regional crises that can only be understood by local history.”

We need your consent to upload this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage additional content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Review your data and accept it to load the content.Manage preferences

From RTÉ News, President Michael D Higgins addresses the 2016 National Famine Commemoration at Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin

By bringing these regional and local contexts to the fore, the atlas enabled readers and scholars to see the famine in all its social complexity. It revealed a society and its customs imploding, as was the case at Attymass in County Mayo, when hunger and disease took their death toll.

The new documentary is a timely reminder not only of the event’s central place in Irish history, but also of its place in the history of North America, Australia and Great Britain. It is also a timely reminder of the relative closeness of famine in time to present generations. When I speak to UCC students amid the ruins of the Bahaghs Asylum located outside of Cahersiveen, Co. Kerry, I am referring to events that are only five or six generations away. And it is the nature of the events themselves and their proximity in time that immediately strikes a chord.

This documentary is also timely because it captures the ongoing research on the famine. This provides new perspectives that deepen our understanding of the event and raise important questions about the nature and structure of Irish society during the years of the famine, and not all of them can be clearly answered.

We need your consent to upload this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage additional content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Review your data and accept it to load the content.Manage preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1’s Blighted Nation, Myles Dungan explores how the Great Famine swept through Ireland in the mid-19th century and changed the country forever.

Ultimately, famines are about failure. The potato failure affected parts of Europe, but nowhere was it more devastating in its consequences than in Ireland. Why? The documentary examines the different national and international contexts in which the crisis unfolded, in particular the role of successive British governments – Tory and Liberal – in responding to the crisis in Ireland, the aid policies applied and the political ideology and religious beliefs that support the answer. and the consequences of these policies.

It is important to note that there were also voices within the British establishment that condemned the nature of the response and what they saw as the mismanagement of Irish affairs by their government. However, the nature of Irish society was also complex and the crisis affected men, women and children in different ways, while the experiences of landowners, land agents, large farmers, small farmers, shopkeepers and traders also varied. . The millions of farmers and workers and their families without access to money to buy food suffered the most in terms of mortality. Those with the means managed to escape the horrors as best they could to carve out new lives on foreign shores and in very often hostile environments.

We need your consent to upload this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage additional content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Review your data and accept it to load the content.Manage preferences

From RTÉ 2fm’s Dave Fanning Show, UCC’s John Borgonovo on why a Native American tribe came to the aid of Ireland during the Great Famine

Famines also bring out the best and worst in human nature. The great acts of charity, kindness and selflessness of humanitarian workers and members of the clergy of different denominations, for example, were frequently overshadowed by more numerous instances of lack of compassion on the part of those in positions of authority. There was also abundant evidence of negligence, ignorance, and indifference to the magnitude of human suffering. Even among neighbors, the will to survive could overshadow all other loyalties and desperate acts committed to ensure one’s own survival.

Television as a medium in a way demands a general narrative, one that always cleans up the mess from the story. However, the maps used in the documentary act as a counterpoint to this often orderly presentation of events and undermine the notion that all Irish people are descendants of those men, women and children who suffered and perished during the famine. To use a phrase coined by Catriona Crowe in connection with research on the revolutionary period in Ireland, such maps in a sense “complicate the narrative.”

We need your consent to upload this YouTube content.We use YouTube to manage additional content that may set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Review your data and accept it to load the content.Manage preferences

UCC’s John Crowley presents a trailer for the documentary The Hunger: The Story of the Irish Famine

The documentary at the end seeks to achieve a balance between information, insight and feeling. As artist John Behan points out, “Death is impersonal when it occurs in such large quantities; it is important to find the human signature.” Beyond the absolute numbers are individual stories such as that of youths found dead on the roadside in Attymass Parish, Co. Mayo. It is in these reports that the true horrors of the famine emerge. It is important to understand and remember what happened on those roadsides.

The Hunger: The Story of the Irish Famine airs on RTÉ One on November 30 and December 7 at 9:35 p.m. Read more about The great famine in the history of RTÉ

The opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the opinions of RTÉ

[ad_2]