[ad_1]

Scientists have gotten their best look to date at three chaotic patches on the icy surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa thanks to decade-old images from a long-defunct spacecraft.

NASA’s Galileo spacecraft spent eight years touring the Jupiter system, between 1995 and 2003, and during that time it made 11 flybys of the icy moon Europa. On Sept. 26, 1998, during one such maneuver, Galileo captured particularly detailed black-and-white images of the moon’s crackled surface. Now, scientists have revisited those images to prepare for future missions to the intriguing world.

“We’ve only seen a very small part of Europa’s surface at this resolution,” Cynthia Phillips, a planetary geologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California and Europa project staff scientist working on future missions, said in a statement. “Europa Clipper will increase that immensely.”

Related: Europa, mysterious icy moon of Jupiter in photos

Europa Clipper is a new NASA mission targeted to launch in in 2023 or 2025 and make 45 passes over the moon. During that time, it will study Europa’s thin atmosphere, icy surface, hypothesized subsurface ocean and internal magnetic field, giving scientists their first look at the moon since the Galileo mission.

To prepare for the new mission, scientists are trying to squeeze all the information they can out of Galileo’s data – and that’s where the reprocessed images come in. During the 1998 flyby, Galileo was able to capture images that showed surface features just 1,500 feet (460 meters) wide.

Such detail is important because it turns out there’s lots going on at Europa’s surface. First of all, it’s strangely young, just 40 million to 90 million years old, one of the freshest surfaces in the whole solar system. (The moon, like Earth and the rest of the solar system, is about 4.6 billion years old.)

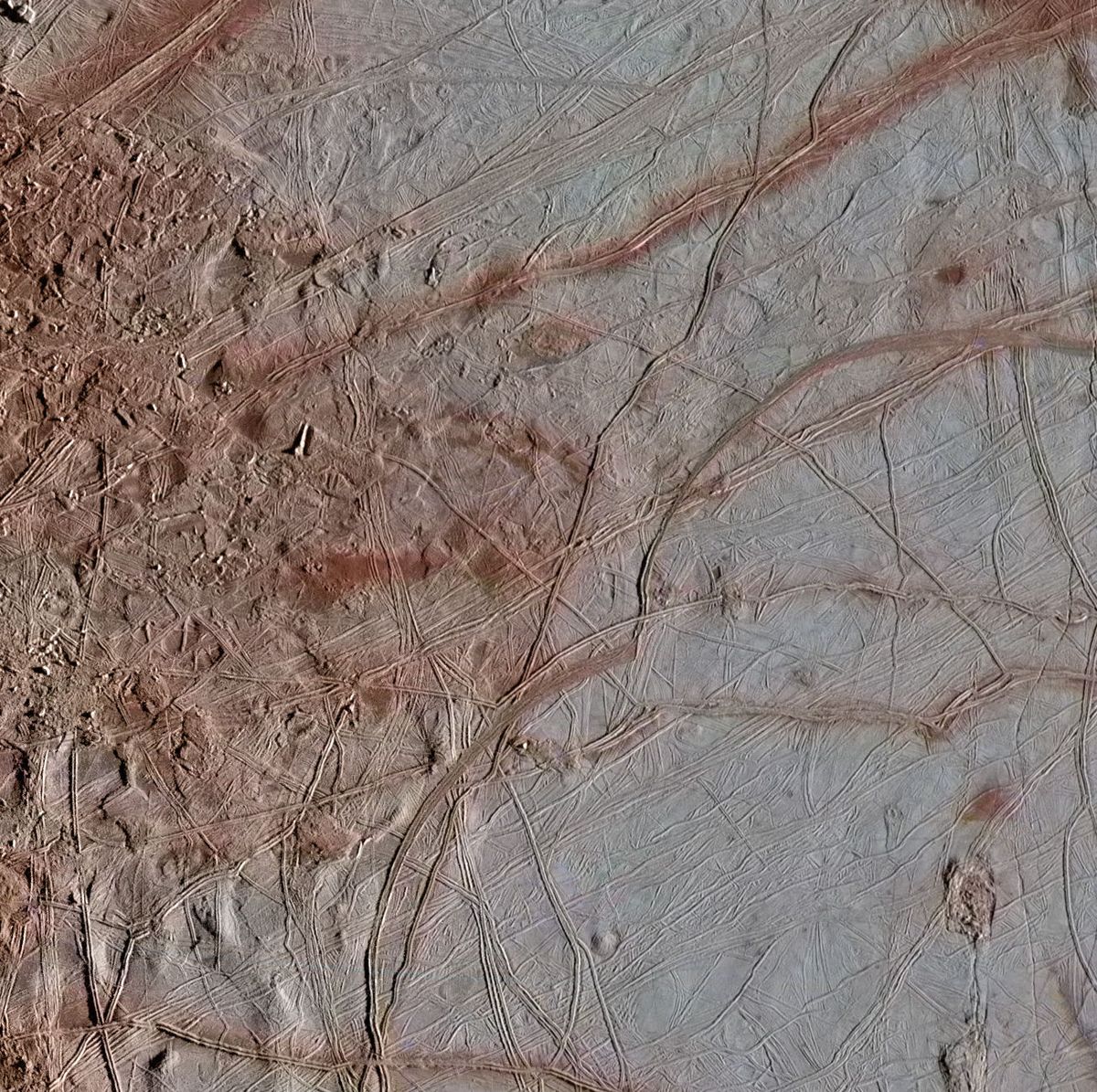

Europa’s ice is also very active: it’s crisscrossed with wide, flat bands where ice has formed between spreading blocks, ridges hundreds of feet tall where ice repeatedly bangs together and separates, and patches so messy that scientists straight up dubbed their structure “chaos terrain. “In these areas, scientists believe that blocks of ice have migrated, popped around and twisted, then been trapped again in ice freezing around them.

That’s nifty, but the Galileo images are grayscale shots of the moon’s surface. And for Europa, color photographs can tell scientists another important detail about the icy story, particularly when image processing experts emphasize small visible differences in color. Those differences reflect chemical composition: white or blue areas have higher levels of pure water ice, whereas redder areas contain other compounds, like salts, which potentially originated in the moon’s hypothesized global ocean.

The new images start from Galileo’s high-resolution black-and-white images and add in color from lower-resolution images, offering scientists the best of both worlds.

Email Meghan Bartels at [email protected] or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

[ad_2]